Boomtown, Texas

In 1926, oil was discovered in Borger, fifty miles north of Amarillo, Texas. My father, William Davis Kirkpatrick, then 24 and single, was one of more than 30,000 people who flocked there. He got a job with the Phillips Petroleum Company, where he worked until he retired in 1963. In Oil Man, the Story of Frank Phillips and the Birth of Phillips Petroleum, author Michael Wallis describes early Borger:

All the roads were dirt and were filled with Model T’s and trucks. The chuckholes were big enough for a small boy to hide in, and the ankle-deep dust of the dry season turned to thick mud when the rains came. Bachelor oil-field workers scrounged up meals at boardinghouses or else gobbled hamburgers for a nickel apiece at Chink-Link, the most popular sandwich stand in town, run by Pappy Oric.

There was little or no sanitation—there wasn’t one flush commode in the entire town. As a result, there were so many rats running down the streets and darting across the sidewalks that in the summer of 1926 the Rig Theater started a bounty system and issued a ticket for every dozen rat tails turned in at the box office.

In 1928, artist Thomas Hart Benton traveled to Borger on a summer sketching trip and wrote down his impressions:

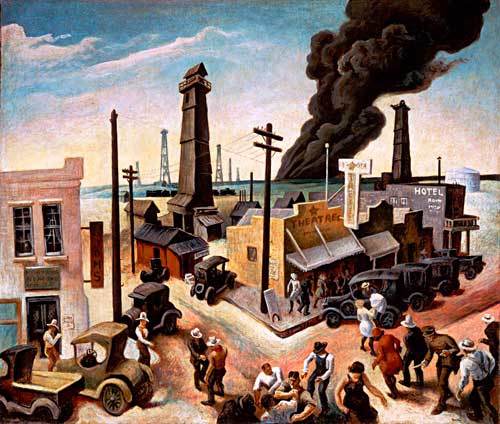

Out on the open plain beyond the town a great thick column of black smoke rose as in a volcanic eruption from the earth to the middle of the sky. There was a carbon mill out there that burnt thousands of cubic feet of gas every minute, a great, wasteful, extravagant burning of resources for momentary profit. All the mighty anarchic carelessness of our country was revealed in Borger. But it was revealed with a breadth, with an expansive grandeur, that was as effective emotionally as are the tremendous spatial reaches of the plains country where the town was set. One did not get the feeling, in spite of the rough shacks and dirty tents in which the people lived, of that narrow cruelty and bitter misery that hovers around eastern industrial centers. There was a belief, written in men’s faces, that all would find a share in the gifts of this mushroom town…. Borger on the boom was a big party…where capital…joined hands with everybody in a great democratic dance. (Seeing America, 213)

Benton’s painting, Boomtown, is in the collection of American art of the University of Rochester. In 2006 the University published Seeing America: Painting and Sculpture in the Collection of the Memorial Art Gallery of the University of Rochester. Classroom Guides to the artworks are now available online to students and teachers. The Guide for Boomtown indicates how Benton worked:

Boomtown is not a “photographically” realistic view of Borger. To enhance the drama of the scene, Benton combined the background billowing smoke and the foreground fight, events he had sketched on two different days in Borger. Despite his desire to develop an American voice Benton was influenced by European styles. The tipped-up viewpoint, the angular shapes of the buildings, and the flatness of the composition reflect the influence of Cubism. To further increase the scene’s energy and vitality, Benton exaggerated the vertical elements and intensified the color palette in the manner he admired in the works of Tintoretto. And to achieve the three-dimensional impact similar to that of Michelangelo’s paintings, Benton molded all his human figures first in clay and studied their poses, shadows, and musculature. The result is a study of energetic rhythm, rich stimulating color, and dynamic objects—the essence of a “boomtown.”

Historic photographs of Borger show two of the elements that he incorporated into this painting–the Model Ts on Main Street and the burning of waste products at the refinery.

Thomas Hart Benton (1889 – 1975) was named for his great-great uncle, Thomas Hart Benton (1782 – 1858), one of the first Senators from Missouri. Thomas’s father, Maecenas E. Benton, served four terms in the US Congress, shuttling his family between Missouri and Washington, DC. The Guide continues: “Thomas had seen the murals in Washington’s public buildings and understood the power of the visual to inform and inspire the viewer.”

By 1933, the boomtown had settled down enough that my father brought his new bride to live there in August, 1933. My mother told of living in a “shotgun” house, three rooms arranged in line, so that one could shoot a gun from the front door to the rear door. A year later, Dad was transferred to a succession of oil camps in the Permian Basin, 300 miles to the south, where my two brothers were born. The family returned to the Panhandle in 1941. I came along three years later.

In 1948 my mother was excited to move from the small camp of Texroy, a few miles southeast of Borger, to Phillips, two miles northeast. It had a population of 4,250 and thriving schools, supported generously by the Phillips Company. The houses were uniformly small (675 square feet), but she sensed opportunity. With my brothers adjusting well to their new school, she put me in a private kindergarten and enrolled in classes at Frank Phillips Junior College to begin completing the degree that she had abandoned during the Depression. At the same time, she started a piano studio in our home that included at least three of my classmates–Carol Cochran, Marjo Hettick, and Carolyn Moore.

By the 1950s, Borger had matured into a more civilized town, at least for whites. Blacks lived in a separate section with unpaved streets. Mom sometimes hired a black woman named Alameda to help clean our house, especially after a 1956 addition doubled the size of the house. North Plains Hospital had much better facilities than Pantex Hospital, where I was born. Though Borger’s population peaked at 20,911 in 1960, we still drove fifty miles to Amarillo for major shopping.

My parents, already members of the First Presbyterian Church, began to take part in other facets of Borger’s cultural life. My mother held piano recitals for her students at the Public Library in Borger, where I also attended meetings of the Edward McDowell Junior Music Club. As soon as Mom attained her degree from West Texas State in 1954, she joined the local chapter of the American Association of University Women. (My Dad kidded her by pretending to confuse the AAUW with the UAW; the United Auto Workers strike was then very much in the news.) Mom persuaded Dad to join the North Plains Knife and Fork Club and attend monthly dinners featuring guest speakers. As a senior in high school, I got to go with them and glimpse Borger’s elite. That same year I joined the choir at the Presbyterian Church. The church, founded in 1927, had dedicated a new sanctuary in 1949. Steve and I were married there June 11, 1966.

A year after our wedding, my parents sold their Phillips house and moved to the farm my Dad and his brother Tom owned in Denton County, just north of Dallas. There they built a new house, one that my mother could at last be proud of. An large explosion in the Phillips Refinery in 1980 caused more people to move their houses from Phillips to Borger. Phillips High School graduated its last class in 1987. Phillips, my home town, is now a ghost town, but Borger endures.

Like any place with an economy based on carbon fuel extraction, Borger has had its share of busts. When I returned for High School reunions in 2007 and 2012, hard times were evident. My family had enjoyed many tasty meals at the Nu-Way Cafe, owned by Carolyn Moore’s Great-Aunt Grace, one of only a few women to own a business in Borger. I found the cafe standing forlorn on Main Street, though Carolyn reports that it’s thriving again today. This article in the Amarillo Globe-News provides a current update.

Thomas Hart Benton wrote that “There was a belief, written in men’s faces, that all would find a share in the gifts of this mushroom town.” My family and my classmates took our share of the gifts of this town. Benefitting from our company-sponsored educations, most of us left for larger cities. In researching this post, I found this unedited list of over one hundred boomtowns in the US and other countries. I’ll be looking for artworks about them.

Leave a Reply