David Smith, Sculptor

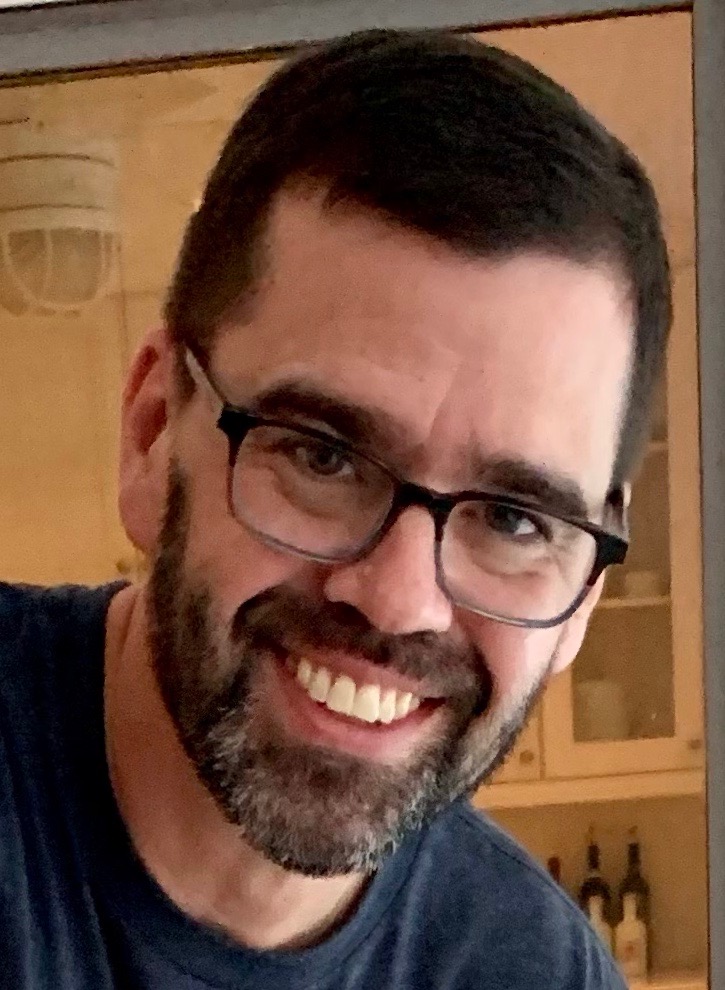

When Steve and I gave our beloved son the name David, we were unaware of a prominent American sculptor named David Smith. It wasn’t until the East Building of the National Gallery of Art opened in 1978 that Washington had a showcase for modern art. I began to notice sculptures by the other David. Maybe it was his name, maybe it was the power of his art, but I found myself captivated by his works. Over the last ten years, I have been photographing them and have begun to cherish them, as I do my son. Here are six works now on view at the National Gallery in Washington.

Smith shows us that a Circle can be wide or narrow and can support different lines of thinking; that a Sentinel might prepare us for what’s ahead. Voltri VII helped me imagine a family of five independent figures riding together in harmony; Cubi XXVII showed me the importance of looking up and keeping the beat.

To learn more about David Smith, the sculptor, click on this 9-minute talk by Sarah Kianovsky at Harvard’s Art Museums, which has a large collection of Smith’s works. Or read this brief biography of Smith I found on the National Gallery of Art website:

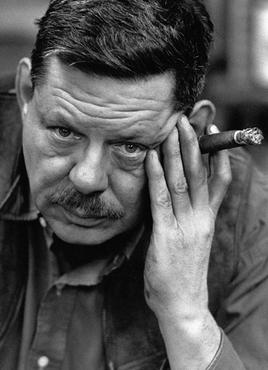

David Smith was born in Decatur, Indiana, in 1906. His mother was a school teacher and a devout Methodist; his father was a telephone engineer and part-time inventor, who fostered in his son a reverence for machinery. After his family moved to Paulding, Ohio, in 1921, Smith developed an interest in art, taking a correspondence course in drawing under the auspices of the Cleveland Art School. Although he spent one year at Ohio University in Athens, Ohio, Smith felt that the studio art curriculum there did not offer the stimulation he sought, and he subsequently dropped out in the spring of 1925. During that summer, he worked as a welder and riveter at a Studebaker automobile factory, where his understanding and love for industrial materials and techniques took root. Much of this rudimentary training proved essential to Smith’s career as an artist.

Smith moved to New York in 1926 and enrolled in classes at the Art Students League, where he met Jan Matulka, a Czech abstractionist. Through Matulka, Smith became familiar with the work of Piet Mondrian, Wassily Kandinsky, and the cubists. By the early 1930s, Smith had begun to incorporate found objects such as shells, bones, wood, and wire into his paintings, adding depth and transforming them into sculptural reliefs. Soon thereafter he began constructing welded steel sculptures, and it is for these works that Smith is best known. Smith developed friendships with other avant-garde artists, including Willem de Kooning, Arshile Gorky, and John Graham. Graham, a painter and critic, introduced Smith to the welded sculptures of Julio Gonzáles and Pablo Picasso, which made a tremendous impression on the artist. By 1934 he had settled into a “studio” at Terminal Iron Works, a foundry in Brooklyn, where he constructed innovative and remarkably diverse sculpture from used machine parts, scrap metal, and found objects.

Throughout his career Smith’s largely abstract work evoked the figure. Often executed in series, his sculptures fully explored particular ideas about materials and composition. In 1965 David Smith’s career was cut short when he died in a tragic automobile accident at the age of fifty-nine.

In May, 2015 Marjo and I enjoyed a trip through the Hudson River Valley. I photographed these works by Smith at Storm King Art Center in Orange County, New York. What a lovely setting for considering both nature and human creativity!

At Kykuit, the Rockefeller estate on the Hudson, I gasped in awe at “The Banquet.” Especially against that backdrop, it was a feast for the eyes!

When Shelby and her family lived in Dallas (2004-19), I loved to visit the Nasher Sculpture Center, where I saw this work, Voltri VI. Only now can I compare it with Voltri VII, on view at the National Gallery in Washington (see above). Voltri VI carries a heavier load than Voltri VII, a deeper commitment to standing upright and carrying on.

In 2020, I was surprised to find “March Sentinel” at my closest art museum, the Norton in West Palm Beach. It was on loan from Crystal Bridges in Arkansas. To me, the rectangles represent books, while the circles are groups of friends. They come together in March Sentinel to create understanding, much as my two book groups do. March Sentinel wasn’t there at the Norton yesterday, but I’ll keep looking for more Smiths there in the future.

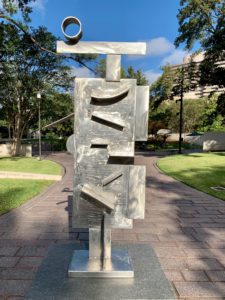

At the Cullen Sculpture Garden in Houston with Shelby last October, I found “Two Circle Sentinel” from 1961. The accompanying sign said that it was purchased by the Museum with funds provided by the Brown Foundation in memory of Margaret Roott Brown. In 1965-66, my senior year at Rice, I was the first president of Margaret Roott Brown College, the sixth of Rice’s current eleven residential colleges. In contrast to the fraternities and sororities on many campuses, the colleges at Rice are unique ways to foster understanding and cooperation among diverse students with distinct interests. (Steve was in Baker College, 1961-66 and our son David was a member of Lovett College 1991-95.) The day before seeing this work I had the opportunity to visit with Ann Patton Greene, Brown’s president in 1970-71, Jae Kim ’24, and the current officers of Brown. I was thrilled to see Brown College thriving so many years later. A sculpture by David Smith seems a fitting memorial.

At the Cullen Sculpture Garden in Houston with Shelby last October, I found “Two Circle Sentinel” from 1961. The accompanying sign said that it was purchased by the Museum with funds provided by the Brown Foundation in memory of Margaret Roott Brown. In 1965-66, my senior year at Rice, I was the first president of Margaret Roott Brown College, the sixth of Rice’s current eleven residential colleges. In contrast to the fraternities and sororities on many campuses, the colleges at Rice are unique ways to foster understanding and cooperation among diverse students with distinct interests. (Steve was in Baker College, 1961-66 and our son David was a member of Lovett College 1991-95.) The day before seeing this work I had the opportunity to visit with Ann Patton Greene, Brown’s president in 1970-71, Jae Kim ’24, and the current officers of Brown. I was thrilled to see Brown College thriving so many years later. A sculpture by David Smith seems a fitting memorial.

Then in November, when I visited Violet and Lilli in Cambridge, my friend Cleta (Rice ’65) and I saw all fifteen of Smith’s “Medals of Dishonor” at one of the Harvard Art Museums. Some of the earliest of Smith’s works, they were a recent gift to Harvard from his estate. Smith made these small bronze medals from 1937-40 to express his opposition to fascisim and war in Europe. This medal is titled “Cooperation of the Clergy.” Angel Gabriel blows the tuba while various religious sects aim the anti-aircraft guns to the heavens. The chalice recalls the spilling of Christ’s blood and the tentacles of an octopus hold open the Bible. More medals may be seen in this album of the David Smith works I have seen over the years. Smith’s use of industrial materials characterizes 20th-century social and political change, as a rural economy became an industrialized nation.

Then in November, when I visited Violet and Lilli in Cambridge, my friend Cleta (Rice ’65) and I saw all fifteen of Smith’s “Medals of Dishonor” at one of the Harvard Art Museums. Some of the earliest of Smith’s works, they were a recent gift to Harvard from his estate. Smith made these small bronze medals from 1937-40 to express his opposition to fascisim and war in Europe. This medal is titled “Cooperation of the Clergy.” Angel Gabriel blows the tuba while various religious sects aim the anti-aircraft guns to the heavens. The chalice recalls the spilling of Christ’s blood and the tentacles of an octopus hold open the Bible. More medals may be seen in this album of the David Smith works I have seen over the years. Smith’s use of industrial materials characterizes 20th-century social and political change, as a rural economy became an industrialized nation.

Thank you David Smith, Sculptor! You deserve a real Medal of Honor. Your art has shown me and many others to consider that there are multiple dimensions to life’s challenges. Your work has encouraged me to be more thoughtful and generous and less rigid. You have given me great joy in sharing my love for art.

Leave a Reply