Morikami Gardens

Though I had visited Morikami Gardens in Delray Beach many times, I had never fully appreciated the concepts behind its design, until I took a two-hour walking tour last week with a group of 19 women from Quail Ridge Garden Club. Our guide, Freya Homer, a professor of Japanese culture at Nova Southeastern University, has served as a Morikami docent for twenty-three years. “This is not a botanical garden, where plants have name tags,” she explained. “The individual plants don’t really matter. What is important is that you experience how the garden appeals to your senses so that you can be in harmony with nature.” On a gorgeous day, I found much harmony. My eyes were exhilarated by the ever-changing vistas; my ears, by various sounds of moving water and birds; my nose, by fragrant flowers; and my taste buds by the delicious Bento box we had for lunch.

This tour offered a compelling introduction to Japanese gardens, but ended before we could visit the waterfall, the Koi feeding pond, the Bonsai Garden, and the exhibit on Japanese life. I will simply have to return again and again. Afterwards, on the Coastal Star website, I found that Freya Horner had published a list of the topics she discussed with us.

What to look for in the Morikami Japanese Gardens

Age: Age is revered in Asia for its stability, endurance and wisdom. That’s why you’ll find older trees with their gnarled roots and trunks covered with lichens. Also notice the yin and yang of these trees’ delicate lacy leaves and sturdy deep roots. [On the tour, Freya called this Wabi-sabi, “rustic elegance” in Japanese. She pointed first to a tree’s wabi (the gnarled roots and lichens), then to its sabi, (a glorious canopy of bright green leaves).]

Bamboo: It’s an important part of a Japanese garden because it propagates itself and grows quickly. You can hear it rustle in a breeze. When bamboo grows thickly it can actually darken the area; when thinned, it brings in light.

Bridges: The bridges do more than join pieces of land. For example, in the Shinden Garden you’ll notice a side-by-side bridge that slows you down so you can’t run and miss what the garden designer wants you to see. And, as you go from one part of the bridge to another, you are provided a new perspective on the scene in front of you.

Deer Chaser: Many years ago, someone came up with this ingenious solution for chasing critters from streams. The combination of bamboo “pipes” filling with water and then periodically depositing it into the stream creates a monotonous and repetitive sound that becomes almost hypnotizing. Although Western children viewing a deer chaser often drop pennies into the water thinking it is a wishing well, it is not.

Ferns: They, like humans, have the ability to grow and prosper in dark times.

Rocks: Rocks can survive the elements of nature, an attribute that also is important in man. The samurai would use rocks to barter for goods. And when they received a new rock, they would name it and have a party. Many of the rocks you see at Morikami were brought in 17 rail cars from Texas; others are the limestone rock native to Florida.

Water: Moving water adds life to the garden. When it is still, it can act as a mirror reflecting what’s around it. You will notice the water in the lake at Morikami is always moving because of the shape of the islands and the fact it’s fed by a sluice. Many of the trees are angled toward the water, providing energy to the landscape and reminding us that we, like trees, need water.

Water Iris: From a bridge in the Shinden Garden (ninth to 12th centuries) you may be lucky enough to see yellow and purple irises growing in the water. The leaves of these water irises each resemble the shape of a samurai’s shield. On May 5 of each year, Japanese mothers take the leaves and grind them to put in the bath water of their baby boys. This is to make the youngsters strong and brave like samurai.

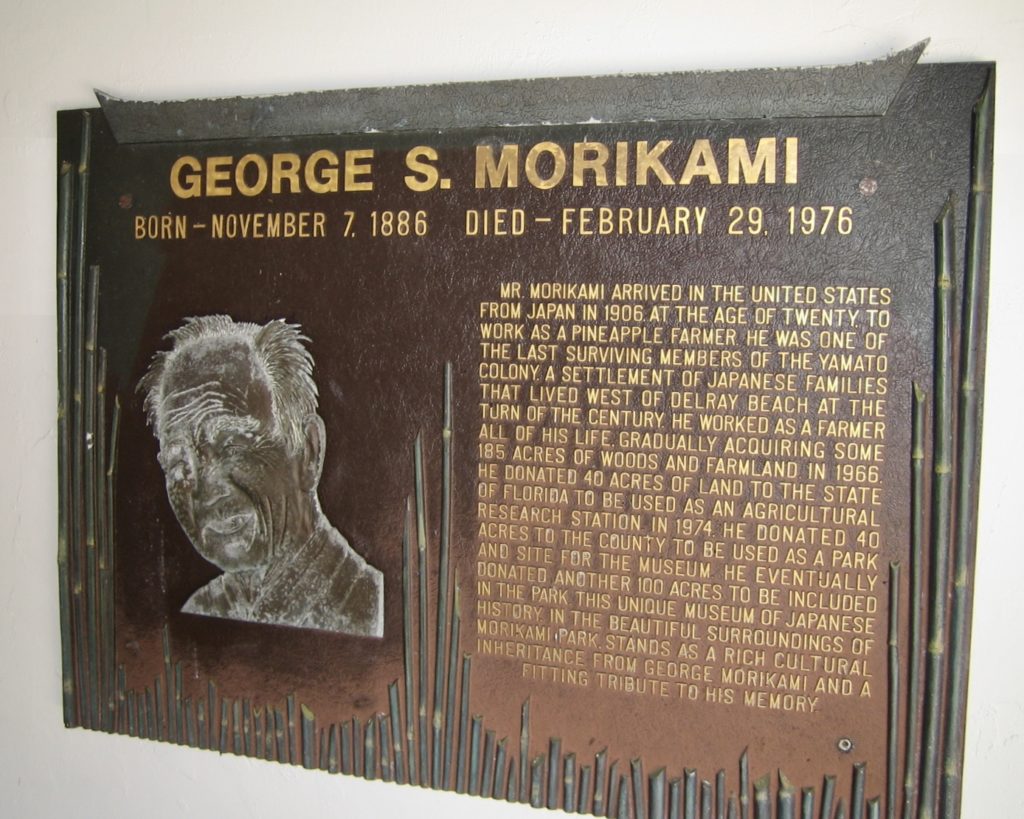

The Morikami Gardens were created on land given to Palm Beach County in 1974 by George Morikami, the last surviving member of the Yamato Colony, who had no heirs. The Colony was a group of Japanese farmers who began growing pineapples in the county in 1905 and shipping them to northern markets. By the beginning of World War II, most of these farmers had returned to Japan. The U.S. government confiscated the land they left for a military installation in 1942. In the closing days of the war, Morikami acquired land west of Delray Beach, several miles from the original colony. He became an American citizen in 1967. By donating the land, he wished to benefit the people of his adopted country and to express his gratitude for the opportunities he had been given. I find his generosity inspiring.

When I go to Morikami, I am reminded of Japanese Gardens I have seen in San Francisco CA and in Fort Worth TX. I am also reminded of friends and relatives I have taken to Morikami over the last ten years, with whom the gardens seemed to strike a chord. Exhibits in the Morikami Museum, objects in the well-curated gift shop, and lunches at the Cornell Cafe enhanced our experiences there.

Leave a Reply