Art, Books & Movies

Five novels I have read over the last several decades have illuminated my understanding of famous artworks. The artists range from the 16th to the 20th centuries: Michelangelo Buonarroti, Johannes Vermeer, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Vincent Van Gogh, and Andrew Wyeth. The two books on Michelangelo and Van Gogh cover their entire careers; the others focus on specific paintings.

Five novels I have read over the last several decades have illuminated my understanding of famous artworks. The artists range from the 16th to the 20th centuries: Michelangelo Buonarroti, Johannes Vermeer, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Vincent Van Gogh, and Andrew Wyeth. The two books on Michelangelo and Van Gogh cover their entire careers; the others focus on specific paintings.

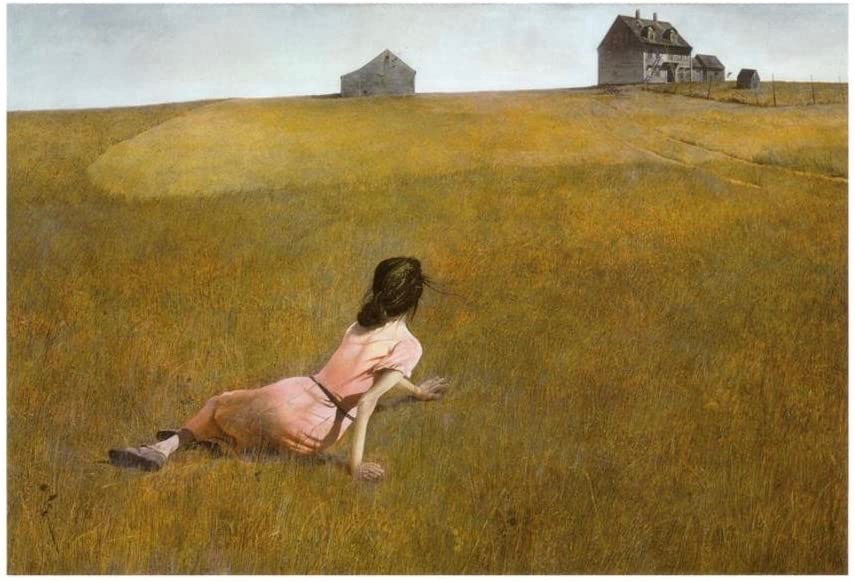

The most recent one I read was A Piece of the World by Christina Baker Kline (2017). Kline imagines Christina Olson and her family, whom Andrew Wyeth got to know over many summers in Maine. In 1948 he painted Christina’s World, which now hangs in the Museum of Modern Art in New York. It was my privilege to discuss Kline’s book with Marjo van Patten’s book group in Kettering, Ohio last Wednesday. There was much to ponder, especially how expectations of women and attitudes toward disabilities have changed over the last century. Neurologists now believe that Olson had a syndrome called Charcot-Marie-Tooth, that affects the nerves to the arms and legs. None of us had ever heard of that, but we appreciated the sensitive way Kline described its effects and chronicled the sacrifices Christina and her brother Al made to keep the family’s farm intact. Wyeth perceived and portrayed her true inner spirit.

Group members in Kettering pondered whether Kline’s novel ranked with the book to which they compare all other novels, Luncheon of the Boating Party by Susan Vreeland (1999). Vreeland imagines how Renoir managed to combine landscape, portraiture, and still life in his 1881 painting set in a cafe on a riverbank near Paris. Renoir’s painting hangs in The Phlllips Collection in Washington DC and has long been a favorite of mine. I remember what a pleasure it was to read Vreeland’s novel. After she read it, Marjo made a special trip to see the painting at the Phillips in 2016. Last June I took the photo below. Marjo’s friends decided that Kline’s book on Wyeth was good, but not as good as Vreeland’s on Renoir.

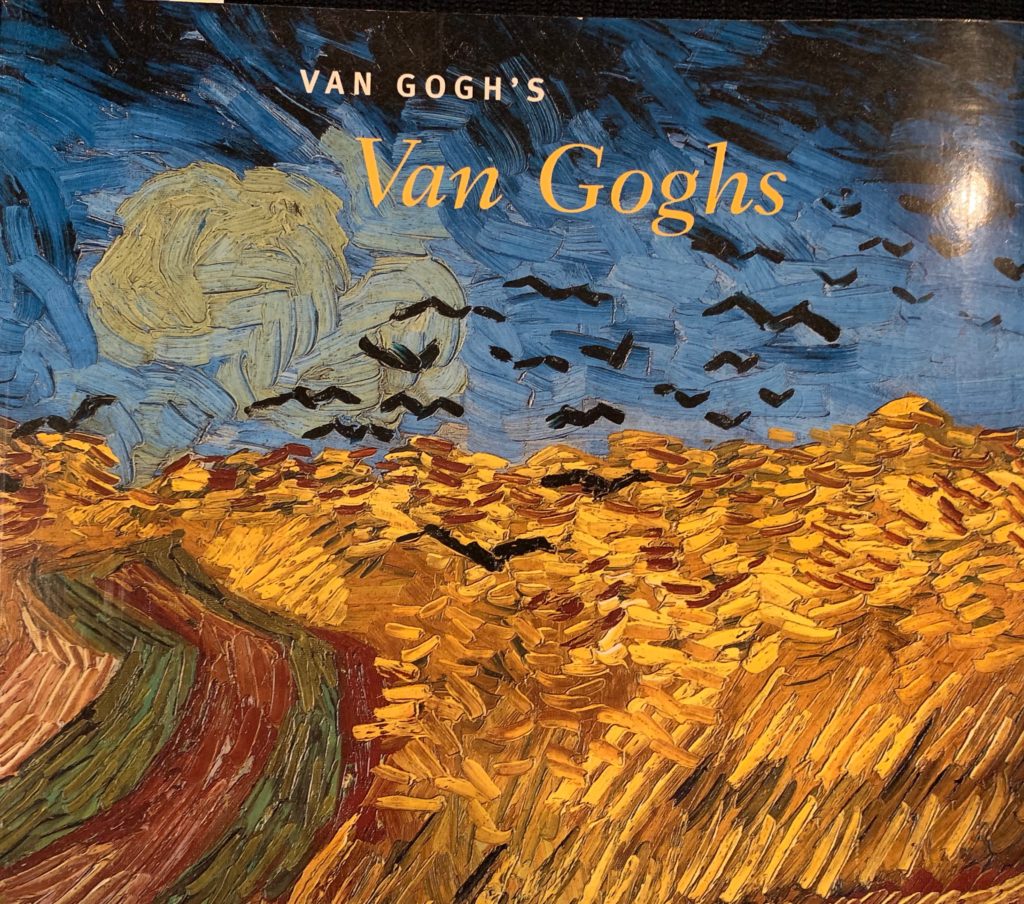

This month, September 2021, I have been fortunate to see two illuminated versions of a wide range of Vincent van Gogh’s works. On September 1, I took my friends Rhea and Nick Hagoort and Angela and Henry Kerfoot to see “Beyond Van Gogh Miami” at the Ice Palace Studio in Miami. On September 17, Marjo van Patten took me to see The Lume Indianapolis, a two hour drive from the Cincinnati airport where she picked me up. The book connection? Lust for Life, a novel written in 1934 by Irving Stone. It was based on the collection of letters between Vincent van Gogh and his younger brother, art dealer Theo van Gogh, over the course of Van Gogh’s brief career, 1880-90. Stone’s novel was adapted into a 1956 film of the same name starring Kirk Douglas.

If you’re thinking of going to see one of the illuminated Van Gogh exhibits now on view in many cities, compare my albums of the two I saw–-one in Miami and one in Indianapolis. There were many similarities; both displayed a new way to capture Van Gogh’s genius. Newfields, however, as the Indianapolis Museum of Art is known, had purchased, rather than leased, the state-of-the-art equipment and projected the images in a more advantageous space than the Ice Palace Studio in Miami, which was separate from any museum. In Indianapolis the accompanying music was reproduced more clearly, too. Newfields also added separate rooms for interactive displays and a mock-up of Van Gogh’s bedroom, where Marjo and I took a photo op. Our friend Carolyn Rhea got a photo at a similar exhibit in Arlington, Texas. All venues apparently include a cafe and gift shop. The ticket price in Miami was $45; in Indianapolis, $25.

Perhaps Newfields plans to project the works of other artists in the future. We noticed that a large, mostly young crowd attended the Friday evening event. When we returned the next day to see more of Newfields, it was full of people wearing tags labeled “Future Member.” Still, my very favorite Van Gogh experience was the exhibition at the National Gallery of Art in DC, from October 4, 1998 through January 3, 1999. I still have this catalog, which I can open anytime to see glorious reproductions of Van Gogh’s works in the comfort of my home. It’s the next best thing to traveling to Amsterdam.

In addition to his book on Van Gogh, Irving Stone also wrote The Agony and the Ecstasy (1961) about Michelangelo, again covering a representative sample of his works during a long career. I made sure to read this book before visiting Italy in 1998. Wikipedia reports details that reveal the depths of Stone’s research:

Stone lived in Italy for years visiting many of the locations in Rome and Florence, worked in marble quarries, and apprenticed himself to a marble sculptor. A primary source for the novel is Michelangelo’s correspondence, all 495 letters of which Stone had translated from Italian by Charles Speroni and published in 1962 as I, Michelangelo, Sculptor. Stone also collaborated with Canadian sculptor Stanley Lewis, who researched Michelangelo’s carving technique and tools. The Italian government lauded Stone with several honorary awards for his cultural achievements highlighting Italian history.

Part of the 1961 novel was adapted to film in The Agony and the Ecstasy (1965), starring Charlton Heston as Michelangelo and Rex Harrison as Pope Julius II.

Do you detect a theme? Artworks, whether individually or collectively, and books about them appeal to wider audiences when they are made into either movies or the immersive displays now available across the United States. Perhaps more “Lumes” or ‘Lumières” are looming ahead. Steve and I saw this exhibit of Chagall’s works at Les Beaux-de-Provence in Southern France five years ago:

What I appreciate about historical novels, movies, and immersive experiences is that each provides a different lens for seeing masterpieces and enriches our understanding of the human beings that created them. I concur with Cathy Capps Bennett, a friend of my friend Carolyn Rhea, who sent this message:

I agree that those immersive images are the future for young lovers of art. They do not compare to actually seeing those paint-laden brush strokes so intently done by VvG, but do introduce this new generation to the beauty of art. I certainly felt an intense connection to VvG just by being literally surrounded by his works, much like I feel in the immersive world of nature. It’s all about the connection to beauty!

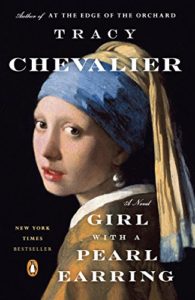

The books on 19th and 20th century artists inspired me to think back twenty years to another terrific book, Girl with the Pearl Earring, by Tracy Chevalier (1999), that fleshes out a 1665 painting by Johannes Vermeer. In January 1996, Marjo came from Ohio to join me in standing in a freezing line to see an extraordinary exhibit at the National Gallery of Art in Washington. Girl with the Pearl Earring was one of the 21 of 35 still-extant paintings that Vermeer was known to have done, that were on display. In 2003 I somehow failed to see the movie, Girl with the Pearl Earring, based on Chevalier’s novel. It was directed by Peter Webber and starred Scarlet Johansson and Colin Firth. I watched it tonight and liked it, especially the lyrical score written by the French composer Alexandre Desplat.

The books on 19th and 20th century artists inspired me to think back twenty years to another terrific book, Girl with the Pearl Earring, by Tracy Chevalier (1999), that fleshes out a 1665 painting by Johannes Vermeer. In January 1996, Marjo came from Ohio to join me in standing in a freezing line to see an extraordinary exhibit at the National Gallery of Art in Washington. Girl with the Pearl Earring was one of the 21 of 35 still-extant paintings that Vermeer was known to have done, that were on display. In 2003 I somehow failed to see the movie, Girl with the Pearl Earring, based on Chevalier’s novel. It was directed by Peter Webber and starred Scarlet Johansson and Colin Firth. I watched it tonight and liked it, especially the lyrical score written by the French composer Alexandre Desplat.

So is there a movie about Andrew Wyeth, the artist whose work prompted this post? Below is a preview of a documentary about Wyeth that indicates that he, like Vermeer, was inspired by women who were not his wife. Besides Christina in Maine, Wyeth had a different muse named Helga Testorf during the time he spent in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania. In the movie of Girl with the Pearl Earring, Vermeer’s wife is portrayed as furious when she discovers that Vermeer painted a servant girl wearing her earring. In Kline’s book, A Piece of the World, Betsy Wyeth is a long-time friend of Christina. Learning about masterpieces reminds me of the depth, height, and breadth of human experience.

Leave a Reply