Industrial Revolutionaries

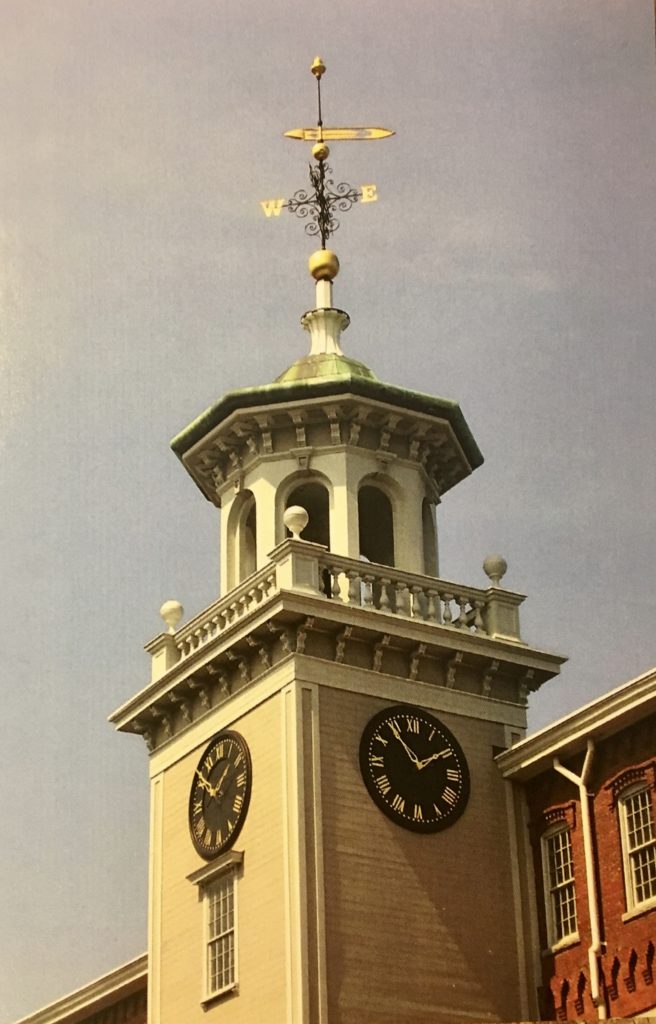

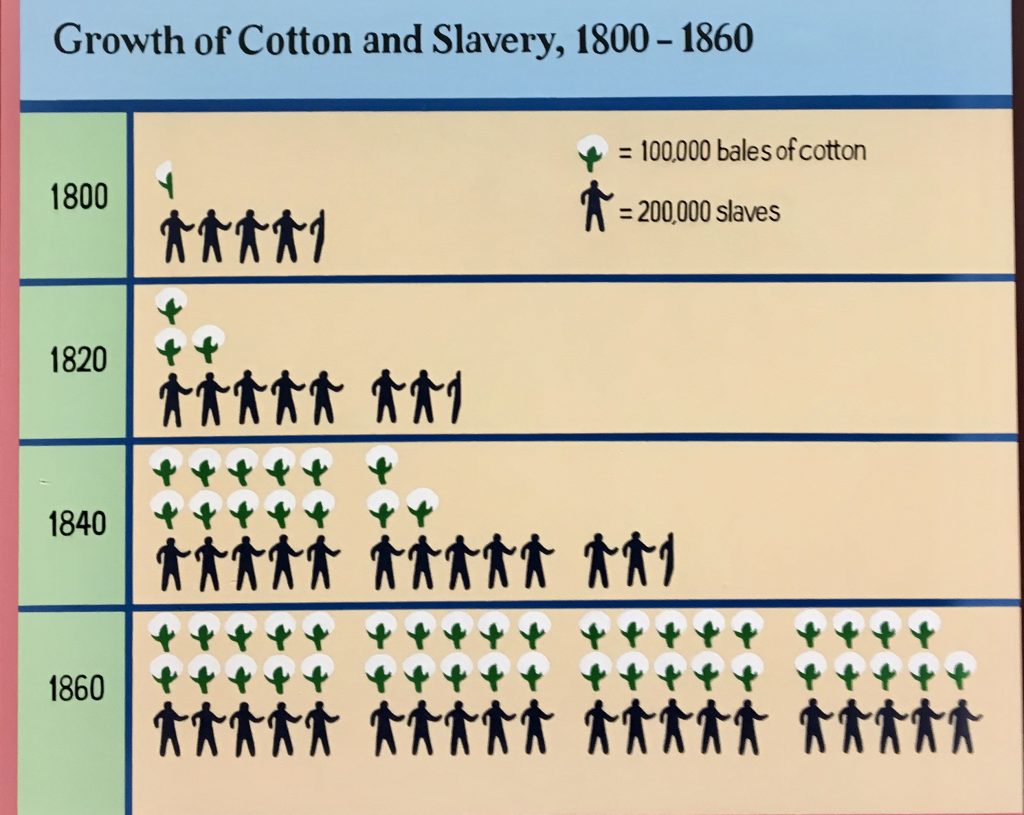

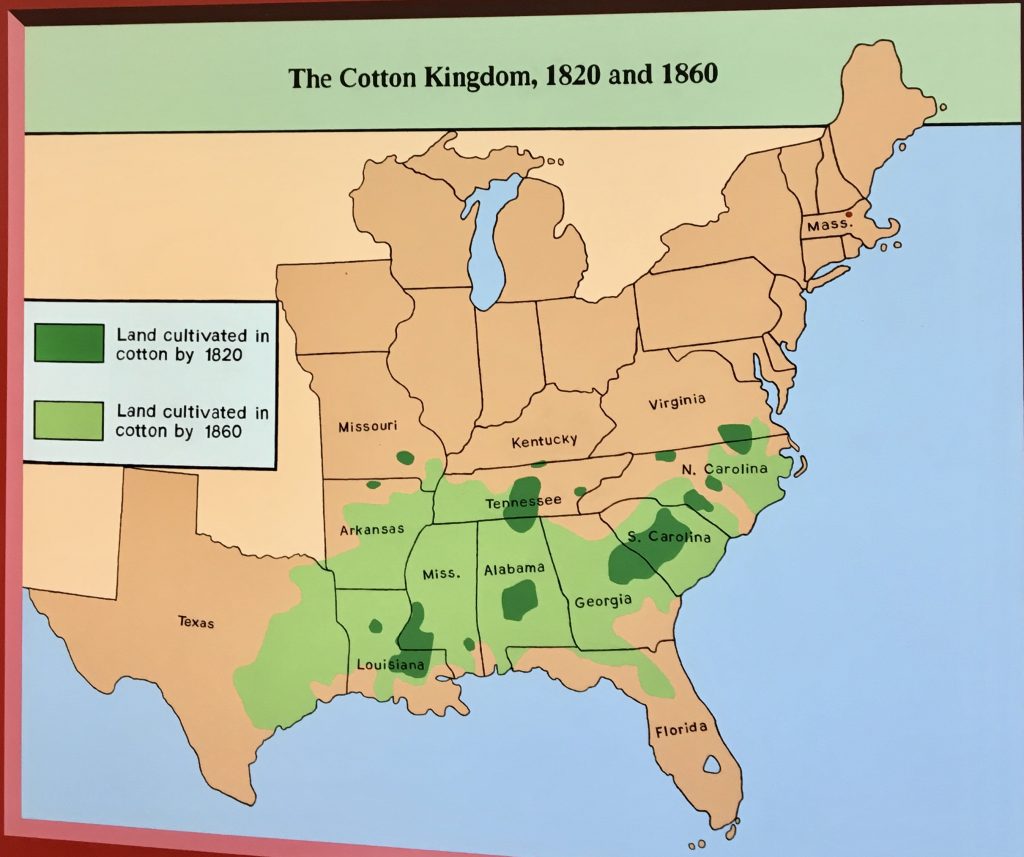

The Industrial Revolution, which began in British textile mills in the last half of the 1700s, has had far-reaching consequences. For example, the British mills’ demand for cotton contributed to the rapid growth of slavery in the Southern United States in the 1800s. Currently, we are realizing industrialization’s long-term effects on our Earth’s climate. This Revolution is an enormously complex subject for citizens to comprehend. A good starting place is the Lowell National Historical Park. On November 13, my granddaughter Violet and I visited the Park’s Boott Cotton Mills Museum and the Tsongas Industrial History Center (a partnership between the National Park and the University of Masschusetts-Lowell) with her Fourth Grade class at Peabody School. Lowell, we learned, was America’s first industrial city.

The Industrial Revolution, which began in British textile mills in the last half of the 1700s, has had far-reaching consequences. For example, the British mills’ demand for cotton contributed to the rapid growth of slavery in the Southern United States in the 1800s. Currently, we are realizing industrialization’s long-term effects on our Earth’s climate. This Revolution is an enormously complex subject for citizens to comprehend. A good starting place is the Lowell National Historical Park. On November 13, my granddaughter Violet and I visited the Park’s Boott Cotton Mills Museum and the Tsongas Industrial History Center (a partnership between the National Park and the University of Masschusetts-Lowell) with her Fourth Grade class at Peabody School. Lowell, we learned, was America’s first industrial city.

[In this blogpost, I show in regular type what I observed the Peabody Fourth Graders experiencing. In italics, I reflect on what I learned as someone who has been fascinated by the Industrial Revolution and Women’s History since earning a BA in History in 1966.]

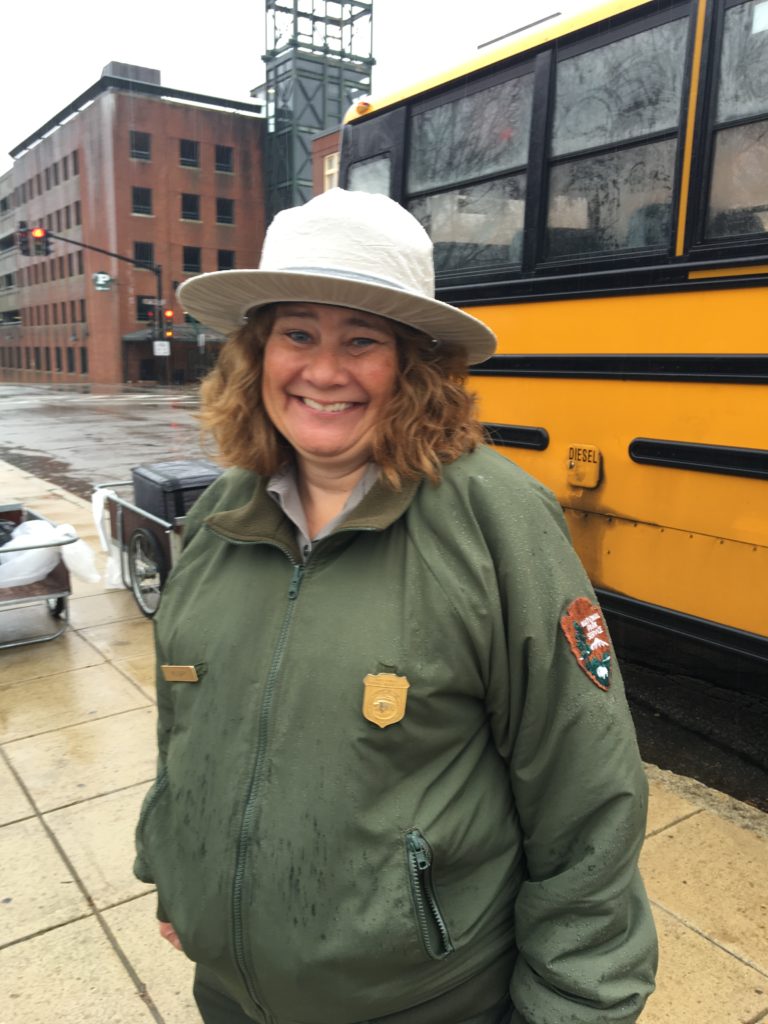

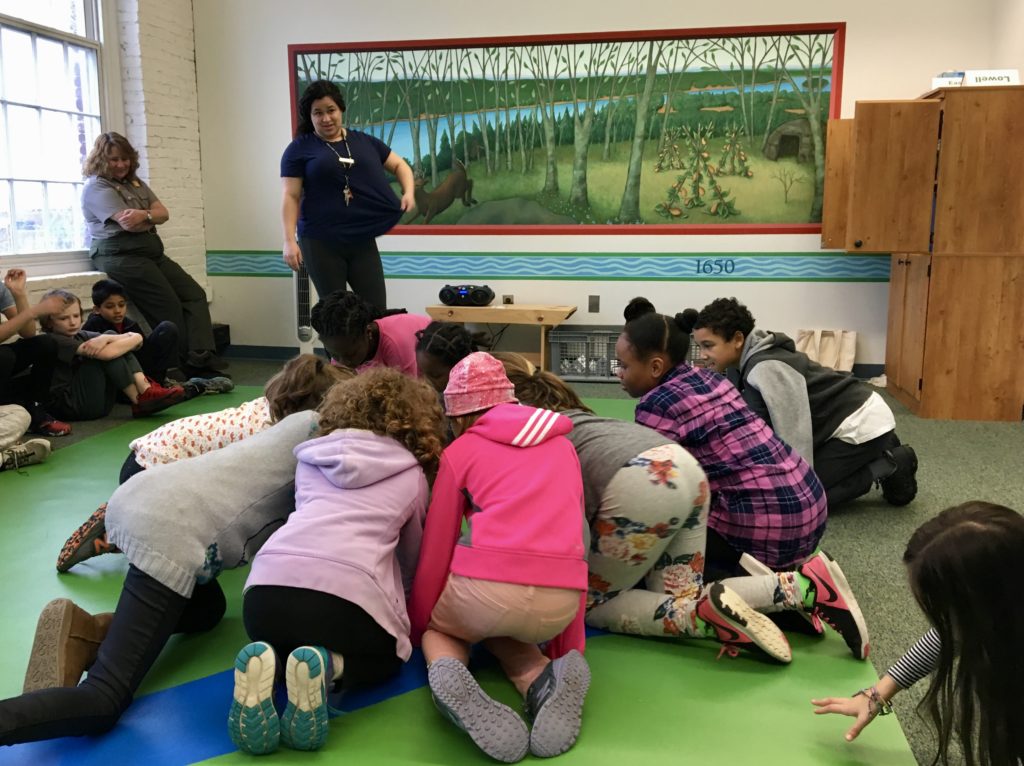

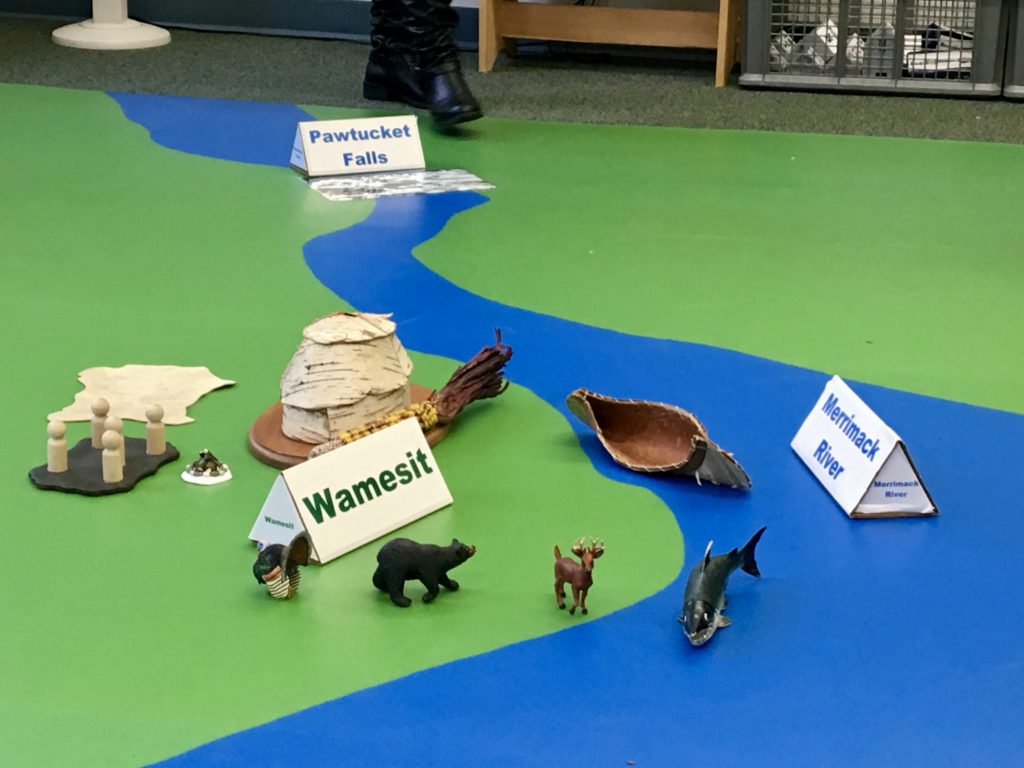

Park Ranger Marybeth Clark welcomed us and introduced Museum Teacher Ana Lisa Colon. After we climbed a spiral staircase to the top floor, Colon began the opening session by involving the kids in displaying settlements on the Merrimack River. Paintings of three contrasting eras related to a timeline that encircled the room. Colon played recordings of environmental sounds appropriate to each painting. With props and signs the students set the stage.

Proceeding to a different room, they compared paintings of two settlements on the Merrimack River: East Chelmsford, the farming community, and Lowell, the mill town.

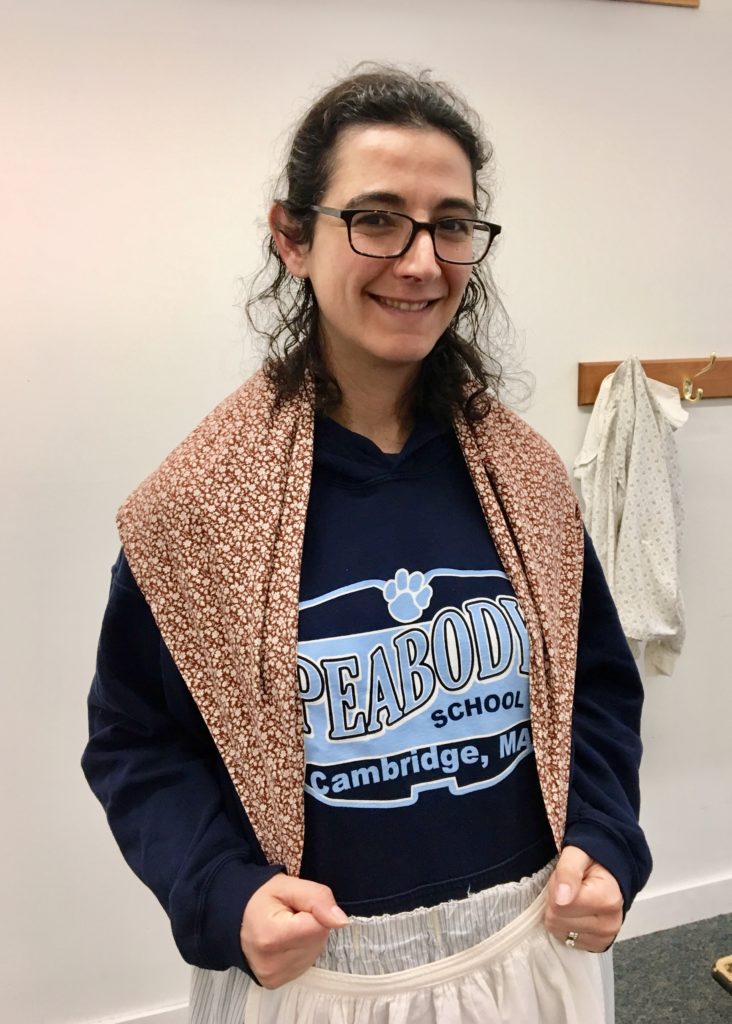

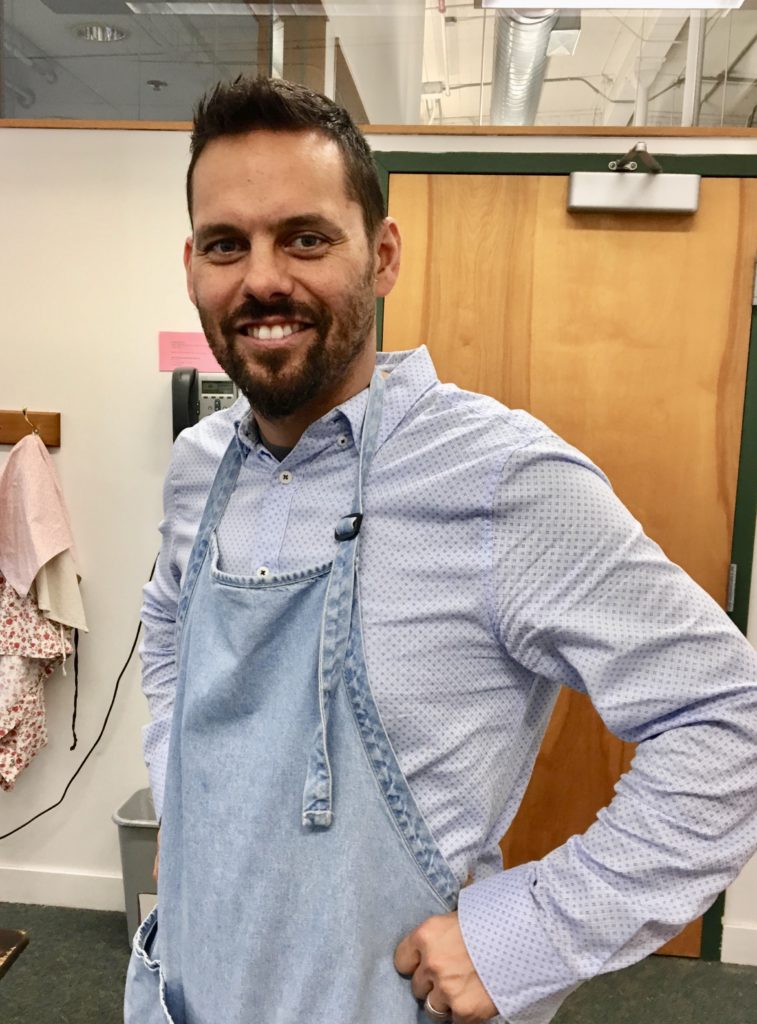

Then students and their teachers tried on the kind of clothes worn by Boott Mills workers.

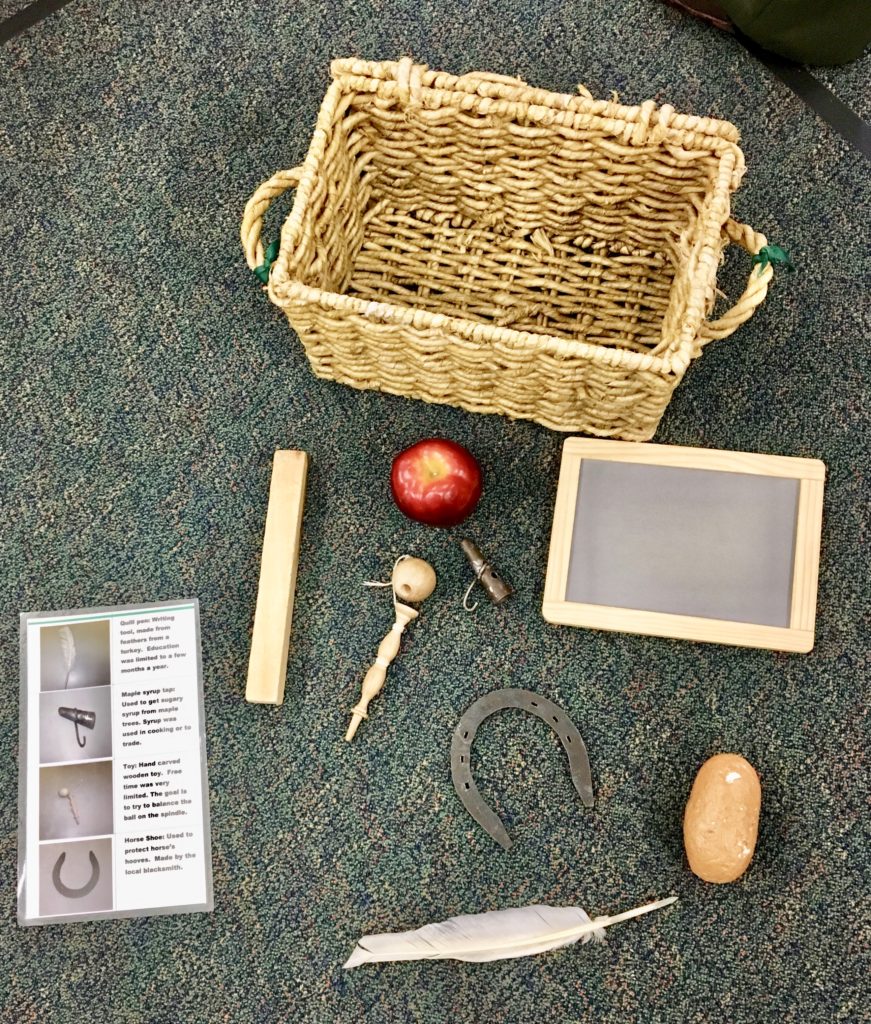

In small groups, students examined various baskets of implements to determine whether theirs related to farming or to cotton milling. Violet’s group studied the contents of the basket below and noted that the apple, the quill pen, and the slate indicated that schools were in session, as they were after Lowell became established.

Afterward, citing the horseshoe, I told Violet that her great-great grandfather (my grandfather) was a blacksmith who made horseshoes in the late 1890s. She quickly rejoined that her own surname, Smith, meant “metal craftsman.” Surely, Harry Raiza (who was born to German immigrants in Uxbridge, Massachusetts in 1874) is smiling down on Violet.

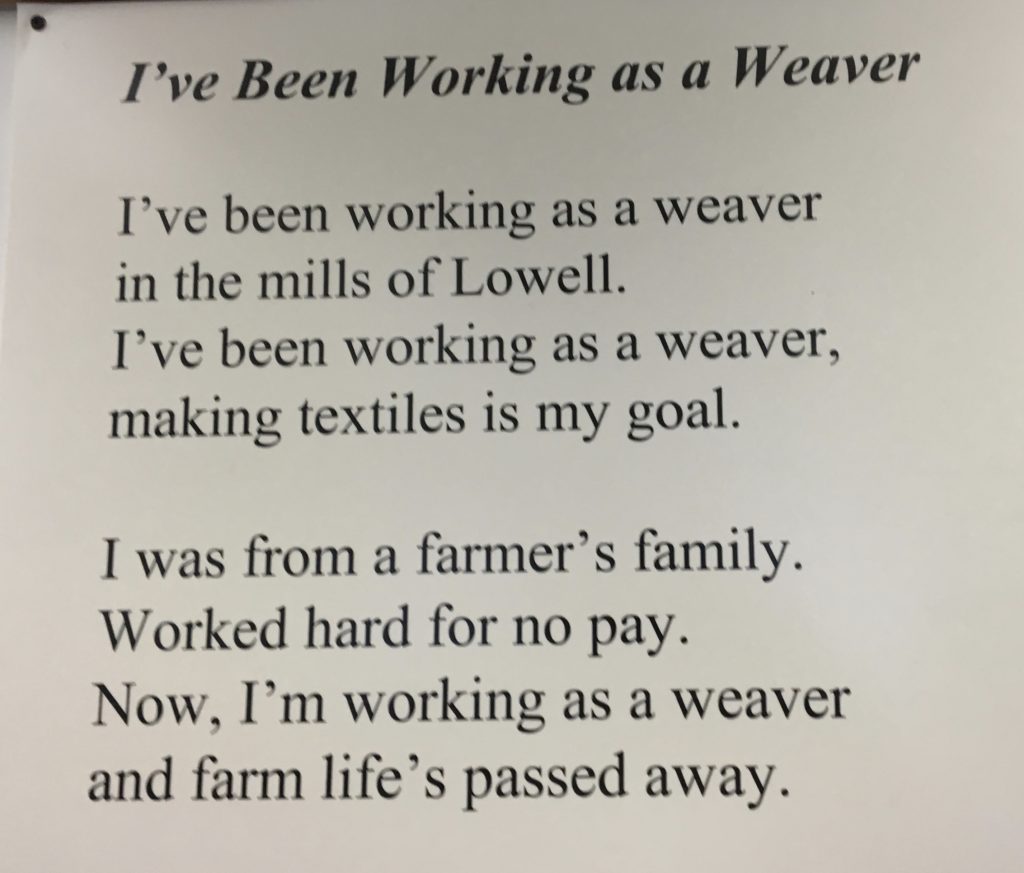

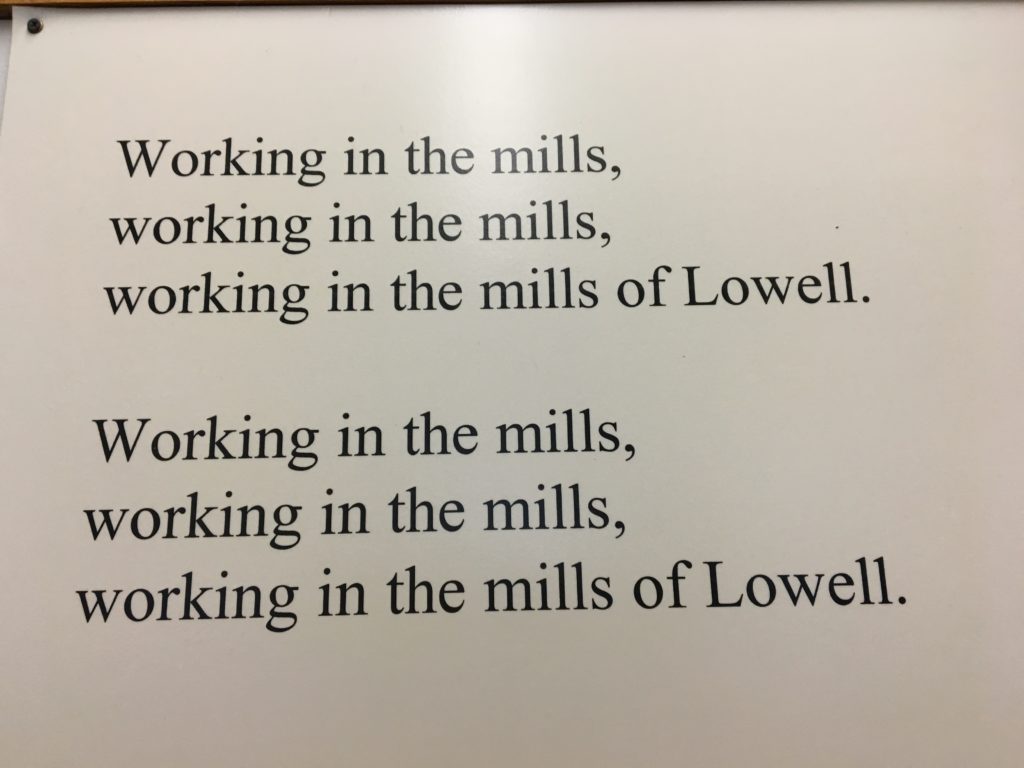

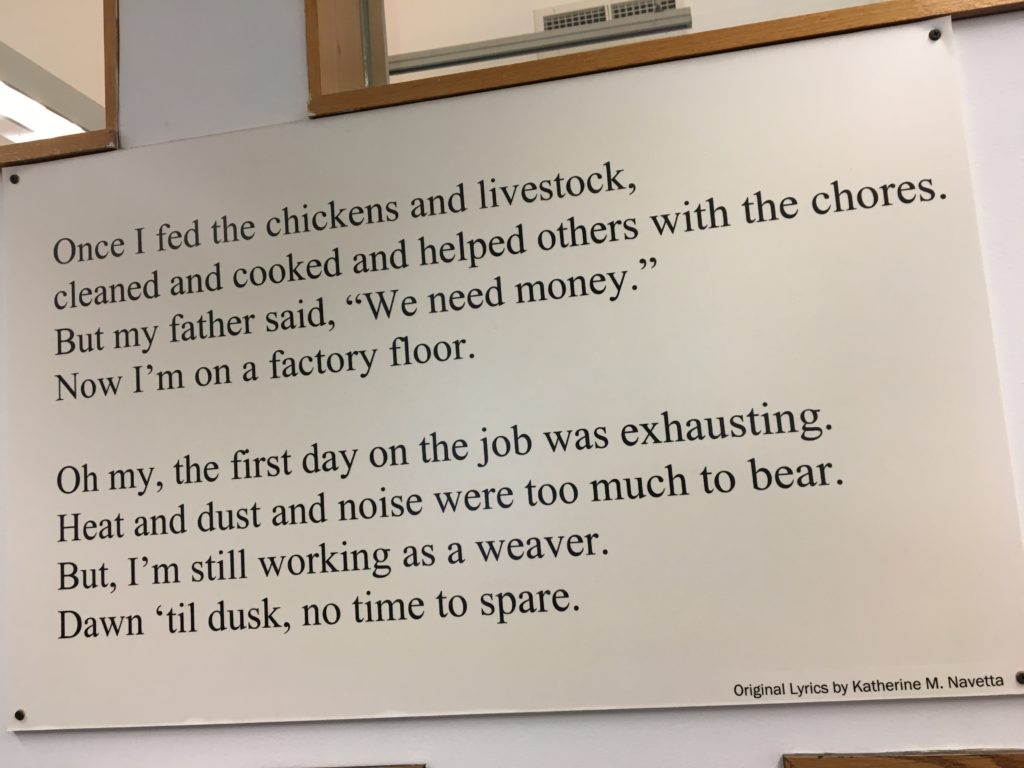

Dressing up as mill workers led to an exploration of who worked in these mills and where they lived. At this point, the power of music was utilized! A song whose lyrics were contributed by a visiting teacher was posted in the room and the students sang it to the tune of “I’ve Been Working on the Railroad”:

A pamphlet I bought in the gift shop, The Lowell Mill Girls, explained:

Lowell’s first textile mill, owned by a group of Boston-based merchants, opened in 1823. Aware of the horrific working conditions in English mills, Lowell’s mill owners sought to avoid Britain’s social and political problems, which they attributed to a poorly paid, poorly housed, permanent working class. Yet the mill owners realized a large labor force was required to operate the hundreds of machines in the factories. They turned to a new, temporary work force: the daughters of Yankee farmers, housed in boardinghouses provided by the textile corporations.

We inspected the Boardinghouse rooms. Each bedroom had two to three beds that four to six girls shared. Each Boardinghouse had a “keeper,” either unmarried or widowed. The keepers were responsible for planning and preparing the meals, keeping the accounts, cleaning, and enforcing the regulations established by the corporations. On the first floor was the kitchen and dining room. Students noticed that the kitchen lacked a refrigerator or a microwave.

Background information extracted from The Lowell Mill Girls pamphlet supports my blogpost title, Industrial Revolutionaries:

By the 1840s, nearly 10,000 New England women had left farms to work for Lowell’s ten major textile corporations. They worked 11 to 12 hours a day, six days a week as “operatives” in the carding, spinning, weaving, warping, and dressing departments. Men held all of the supervisory jobs and skilled positions such as mechanic and loom fixer. Women earned from $2.00 to $3.50 a week in the 1830s. After $1.25 was taken out each week for room and board, the mill girls could save or spend as they wished. These wages compared favorably to those of domestic service, teaching, or sewing, the few alternatives open to women. Lowell offered novel opportunities to former farm girls: lectures, libraries, theater, balls, and a variety of religious activities. An average stay lasted from one to four years, after which the mill girls returned to their farms, married, sought permanent employment, or attended one of the few schools open to women at the time. [NMount Holyoke opened in 1837.]

These Mill Girls were Industrial Revolutionaries, trying a new lifestyle, proving that they were valuable, gaining self-confidence, and changing society in profound ways.

On the way to lunch, we passed through a vast hall, still producing cotton cloth. It was so noisy! This video is but a glimpse; the sound was much more intense. Many workers became deaf. Only one worker that day was supervising scores of looms; he wore ear protection.

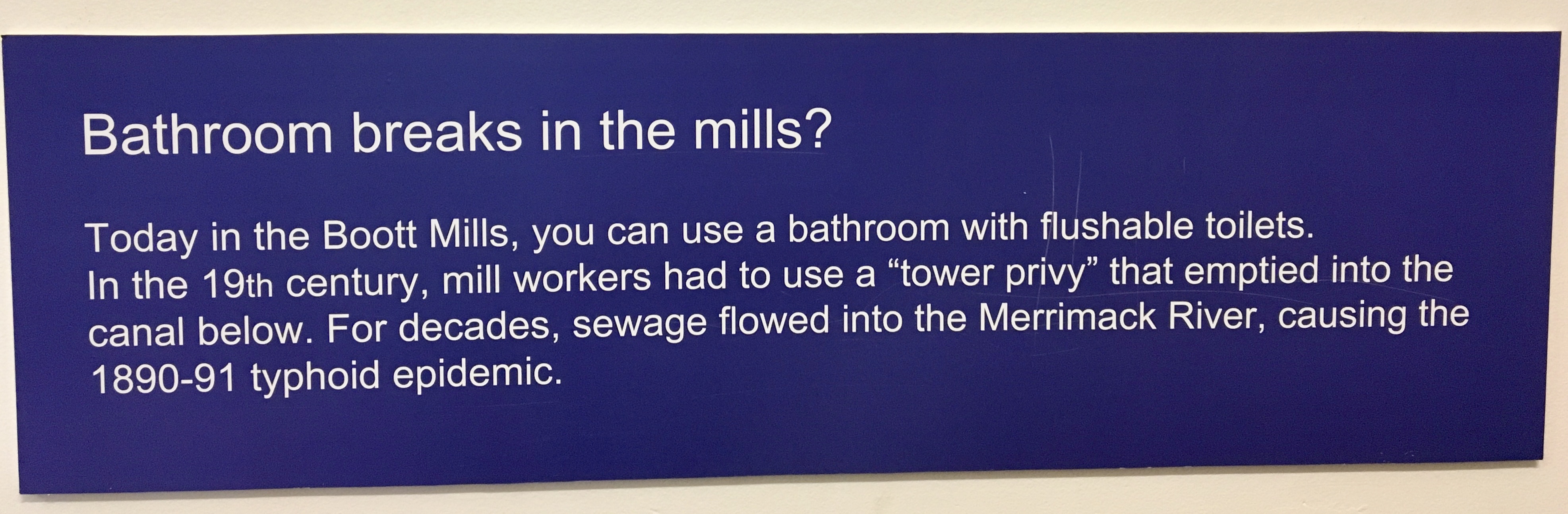

We noticed this sign near the restrooms:

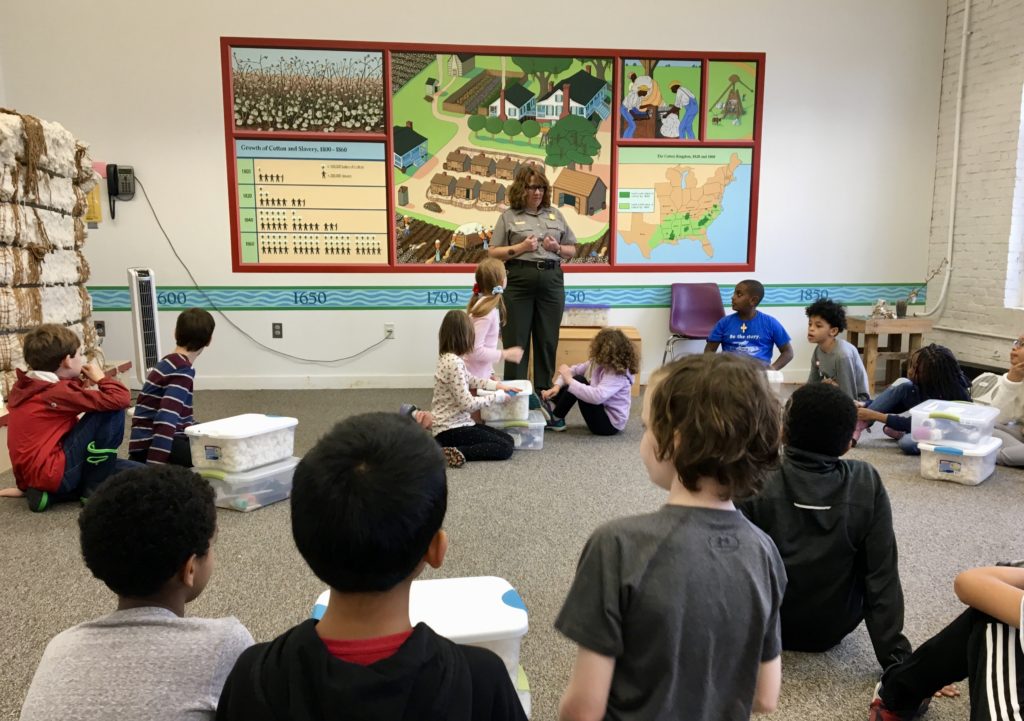

After lunch, we learned more about the raw material, cotton, that Boott Mills processed. Park Ranger Clark led a discussion of plantations in the South that produced the cotton for the mills. In my history studies, I had somehow missed the link between demand for cotton in Britain and the growth of slavery in the American South. I certainly never learned that in the fourth grade in Texas.

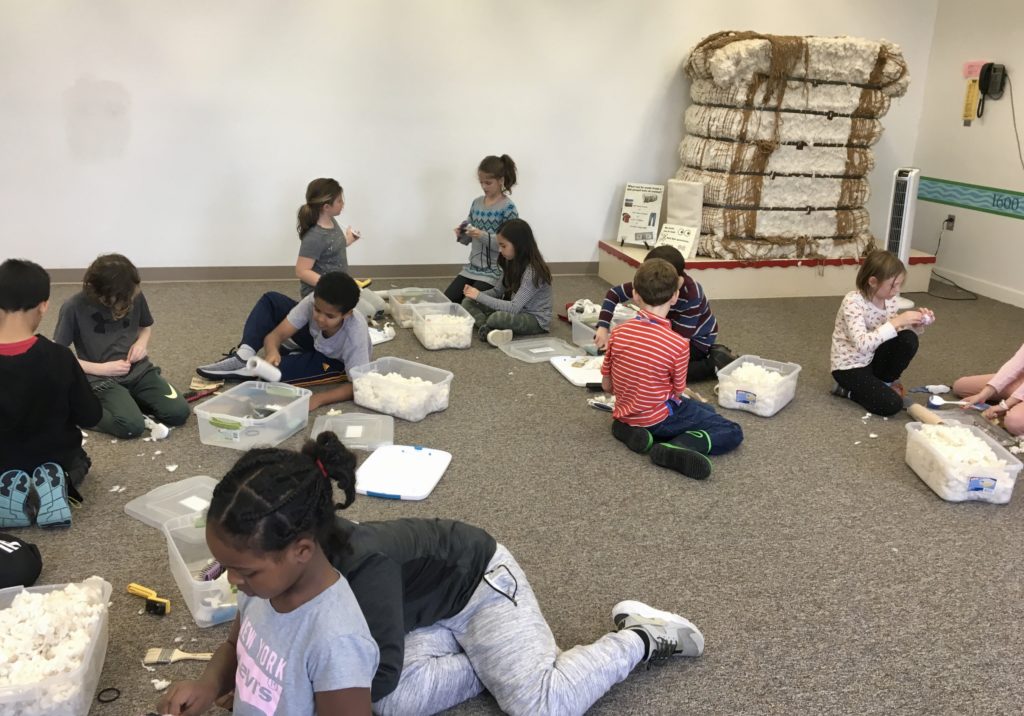

In the the Cotton Kingdom picture above, slaves are shown using a press to form a bale (500 pounds) of cotton. Such a bale is shown in the picture below. Students learned that working one day, one person could remove the seeds from only one pound of cotton. They tried improving their yields with forks and brushes.

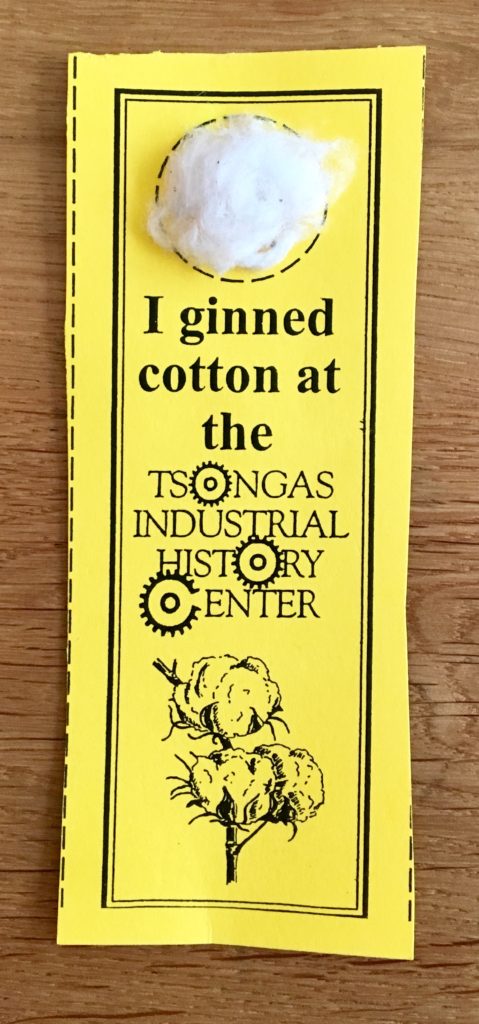

Then they each got a chance to operate a hand-cranked version of Eli Witney’s cotton gin. Later I told Violet that her Great-Great Grandfather Raiza had managed a mechanized cotton gin in Woodson, Texas in the 1940s and 50s. Sadly, I realize that I did not appreciate what he did.

Ranger Clark concluded the day by saying “everything we have today comes from the Industrial Revolution, which started in America here in Lowell.”

I disagree. Not everything! For me, the day reinforced my feeling that cotton clothes, microwaves and cell phones are just stuff. What I experienced was the non-material, intangible benefit of seeing a historic Massachusetts town through the eyes of fourth graders, gaining a better understanding of powerful forces in our history, and sharing that experience with my dear granddaughter. My only suggestion is that in the session on cotton ginning the children get a chance to sing the old folk song “Pick a Bale of Cotton.”

I disagree. Not everything! For me, the day reinforced my feeling that cotton clothes, microwaves and cell phones are just stuff. What I experienced was the non-material, intangible benefit of seeing a historic Massachusetts town through the eyes of fourth graders, gaining a better understanding of powerful forces in our history, and sharing that experience with my dear granddaughter. My only suggestion is that in the session on cotton ginning the children get a chance to sing the old folk song “Pick a Bale of Cotton.”

Cost/benefit ratio: I was told that the bus for transporting about 50 people (two classes, teachers, and chaperones) from 9:15 am to 2:15 pm cost $700. The Park charges $225 per class for field trips, including teachers and chaperones. The benefit? Priceless! I hope Violet and her fellow students will be able to take advantage of more of the Park’s programs: Yankees and Immigrants (Grades 4 – 12), River as a Classroom (Grades 5 – 8), and Industrial Watershed (the Environmental Impact of Industrialization for Grades 7 – 12).

Many thanks to Park Ranger Marybeth Clark and Museum Teacher Ana Lisa Colon for a fascinating day of discovery and for the bookmarks each student got to take home.

Leave a Reply