Beethoven’s 251st

As the pandemic surged a year ago, there was scant celebration of Ludwig van Beethoven’s 250th birthday. Trying to make up for this loss, tonight I hosted a small recital in my home to mark his 251st. My student, Luke Reese, was first on the program with “Ode to Joy” from Beethoven’s 9th Symphony. It’s also the hymn tune “Joyful, Joyful, We Adore Thee.” Sing along with these words I wrote for my students back in 2000:

On the sixteenth of December we remember Beethoven. He was born in Germany in seventeen and seventy. Soon he moved to big Vienna, Haydn and Mozart both were there. There he wrote his greatest music, music that we all adore. Thirty-two piano sonatas, just one concerto for violin, and nine famous symphonies, the last includes this Ode to Joy.

My first piece was “Für Elise”–not just the ringtone, but all five pages. This rondo (A-B-A-C-A) contrasts the beauty of a woman with a man’s anxiety and trepidation in her presence. Beethoven, a lifelong bachelor, was challenged when it came to women. No one has yet identified exactly who Elise was, but his piece about her is universally loved. It’s a pleasure to recall how very beautifully Elise Cohen and Diana Fang performed Für Elise on recitals in my studio.

The image of Beethoven shown here is one I photographed at the Beethoven Haus in Baden, just south of Vienna, where Beethoven lived during the summers of 1821 through 1823. My brother Joel and his wife Elisabeth have an apartment in Baden. A special memory is when they hosted Lilli, Violet and me there in August 2015 and showing us where Beethoven lived when he composed his 9th Symphony.

Next on the program was Sonata Pathetique, Opus 13, Second Movement, the Adagio Cantabile. I have always loved this piece. As I played it tonight, I realized that it, too, is a rondo, contrasting lush beauty with troubling emotions. My teacher at Catholic University 1992-96, Thomas Mastroianni, noted that the first contrasting section (B section) has a throbbing pulse. Alan Mandel, my teacher at American University 1975-78), marked the C section as “sinister.”

Karl Haas performed the Adagio Cantabile to introduce his National Public Radio show, Adventures in Good Music. I used to listen to his program on WGMS in Washington every afternoon at 2 o’clock before my students began to arrive. Haas, who studied piano with Artur Schnabel, encouraged me to seek background information about each piece I played or taught. Haas served as President of Interlochen Center for the Arts in Michigan from 1967-1971. My friend Honnie McClear, an Interlochen supporter for years, took me to visit the Interlochen Center when Steve and I visited her and Dick last September. Tonight she came to hear me play.

More fond memories: Lilli playing Adagio Cantabile almost every time she visits; Emily Marshall playing it on her solo recital in June 1995; Cecily Hutton playing it on her senior recital in April 2001; Michael Salvatierra playing all three movements of Opus 10, No. 1 on his senior recital in March 1998; and Diana Fang playing all three movements of Opus 13 on her senior recital in June 2008.

My final contribution was the first movement of Sonata Quasi una Fantasia, better known as the “Moonlight” Sonata, Op. 27, No. 2. First, I read a passage from one of my all-time favorite books, A Soldier of the Great War by Mark Helprin. The scene is south of Rome in August 1964. Alessandro, the old soldier from World War I, and Nicolò, his near-sighted apprentice, are walking through the hills. Alessandro has just lent Nicolò his spectacles.

Look! The moon.

Alessandro turned to the east. His cane clattered down upon the rock as he caught sight of a tiny orange dome, rising coolly, unlike the molten sunrise, from behind the farthest line of hills.

The arc rapidly turned into a silent half circle, spying upon them with its old and tired face. It had about it the air of being intensely busy, as if its occupation with the task of floating in perfect orbits had made it justly self-absorbed.

“The whole world stops as this stunning dancer rises,” Alessandro said, “and its beauty puts to shame all our doubts.”

It is like a dancer, Nicolò thought, as the perfectly round moon began to float airily above the silhouetted hills it had begun to illumine. “So smooth,” he said.

“Without saying anything, it says so much,” Alessandro continued. “In that sense, it’s better than the sun, which is always holding forth, and butting at you like a ram.”

Because of Alessandro’s spectacles, Nicolò was able to see that the moon had mountains and seas. His sudden apprehension of the moon, so close and full, riding over them like a huge airship, endeared it to him forever. For perhaps the first time in his life he was lifted entirely outside himself and separated from his wants.

Not only does Beethoven’s melody begin with the same rhythm as the words “Look! The moon,” but the triplets in the accompaniment evoke the rolling hills through which Alessandro and Nicolò walk. Indeed, the moon tonight is nearing fullness. I hope all my readers will think of Beethoven when they see the moon. I’m reminded that Anne Rebull played all three movements of Op. 27, No. 2 on her senior recital in June 2000. A full moon brings back so many happy memories to me. Here’s a video I recorded for a virtual Moonrise Party in April 2020.

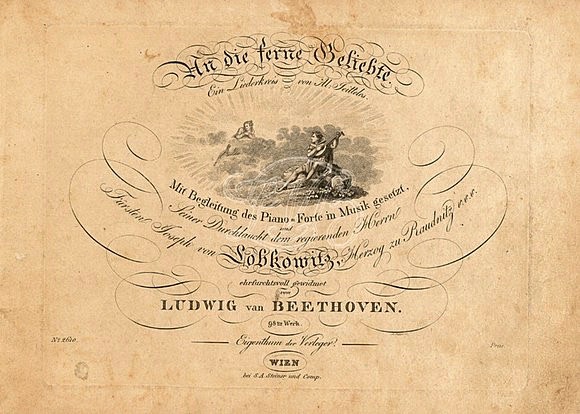

Tonight’s recital concluded with my teacher, Lisa Leonard, playing Franz Liszt’s transcription of Beethoven’s song cycle, An die fern Geliebte (To the Distant Beloved), a work I had not heard before. Lisa, Professor of Collaborative Music at Lynn University in Boca Raton, cited Beethoven as a pioneer in this field. An die fern Geliebte was actually the first song cycle and became a point of departure for the cycles of Schumann and many others. In his masterful biography of Beethoven, Maynard Solomon notes that this work, composed in April 1816 to a Romantic pastoral text,

occupies a special place in Beethoven’s life and work. It seems safe to say that it bids farewell to his marriage project, to romantic pretense, to heroic grandiosity, to youth itself. It is a work that accepts loss without piteous outcry, for it preserves intact the memory of the past and refuses to acknowledge the finality of bereavement.

Lisa explained how Liszt’s transcription melds both the singer’s melody and the piano accompaniment into one piano solo. Such a work exemplifies how influential Beethoven was for succeeding musicians. Lisa’s playing of the complicated score was magnificent. Want to hear Beethoven’s original? YouTube to the rescue:

I so appreciated Lisa and her son Luke joining me in honoring Beethoven. Here they are at their house six weeks ago. Steve was very helpful tonight in welcoming our guests and serving refreshments. On view was a small blanket my daughter Lilli had sent me in the 90s. It was woven to show the opening of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, Churchill’s famous victory motif in World War II. My son David reminded me to listen to “A Fifth of Beethoven” on Spotify. I imagine Shelby going to her piano and playing Ode to Joy. Most of all, thank you Beethoven for continuing to bring JOY to the world.

I so appreciated Lisa and her son Luke joining me in honoring Beethoven. Here they are at their house six weeks ago. Steve was very helpful tonight in welcoming our guests and serving refreshments. On view was a small blanket my daughter Lilli had sent me in the 90s. It was woven to show the opening of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, Churchill’s famous victory motif in World War II. My son David reminded me to listen to “A Fifth of Beethoven” on Spotify. I imagine Shelby going to her piano and playing Ode to Joy. Most of all, thank you Beethoven for continuing to bring JOY to the world.

Leave a Reply