Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes

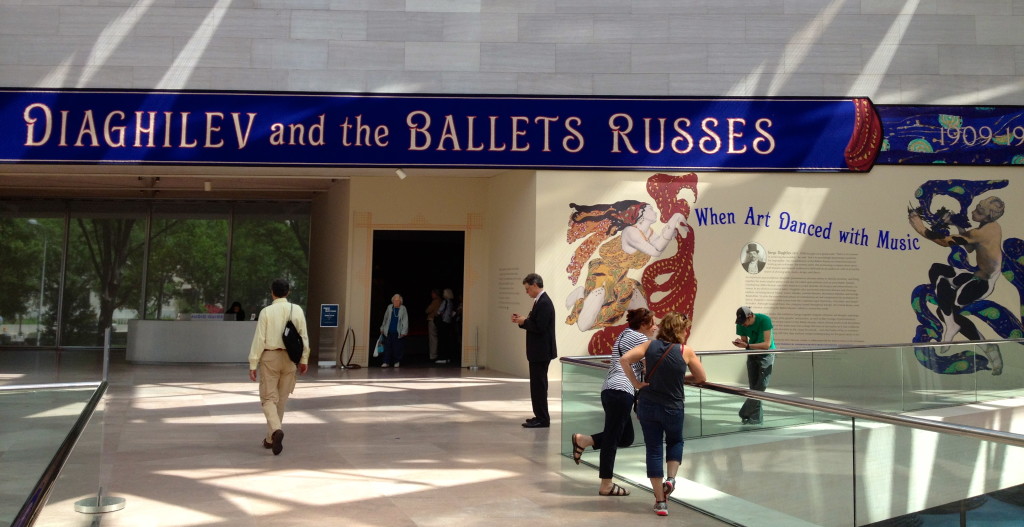

“When Art Danced with Music” is the apt sub-title of this wonderful exhibition at the National Gallery of Art East Building from May 12 – October 6, 2013. I have visited it four times, more than any other exhibit in the last 45 years. Colorful sets and costumes and several short films of famous performances make 100-year old works come alive. Since high school I have loved the music of Stravinsky’s Petrushka*, Debussy’s The Afternoon of a Faun, and Prokofiev’s The Prodigal Son. In January 2012 I was thrilled to see the Mariinsky Ballet dance Firebird and Schéhérazade at the Kennedy Center. Both were premiered by Ballets Russes. This exhibition brochure shows a picture of the Schéhérazade stage setting on which the Mariinsky set was based. It also shows the gold-burnished backdrop for Stravinsky’s Firebird, which hangs near a 7-minute video re-imagining this historic ballet with 21st-century techniques. Here’s a 2-minute sample

The Firebird – V&A from newangle on Vimeo.

*Here’s a video telling the story of Petrushka and how the Boston Symphony Orchestra has performed it over the last century.

After seeing this exhibit alone on May 17 and on June 10 with the Austrians, I returned on July 29 with my friend Jacqua. Jacqua and her friend Wendy had visited the exhibit the week before, when there was a live performance by four Russian dancers recreating some of Ballets Russes repertoire. Wendy, a writer for Dance Magazine, posted an especially insightful review on her blog: Forbidden Love in Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, discussing Diaghilev’s ground-breaking artistic and psychological achievements. Alastair Macaulay wrote a contrasting, but equally enthusiastic review in the New York Times. Jacqua and I loved the music above all and were delighted to find in the gift shop a 3-CD compilation of the music Ballets Russes employed. Here’s a fascinating story from the liner notes:

Firebird–a ballet based on the Russian folk tale of a magical glowing bird that is both a blessing and a curse to its captor–was to be the first Ballets Russes production for which the music was specially composed, but when Arensky took too long providing his score Diaghilev passed the commission to the young composer Igor Stravinsky. Anna Pavlova was to dance the lead role but withdrew after declaring Stravinsky’s music “noise” and her place was taken by Tamara Karsavina, who was told by Diaghilev “Mark him (Stravinsky) well…he is a man on the eve of celebrity.” He was proved absolutely correct and the ballet not only marked Stravinsky’s breakthrough but the start of a long and mutually beneficial relationship between composer and impresario.

On September 23, I returned to this exhibit yet again with my long-time friend Carolyn. Carolyn had seen an exhibit of the costumes in Madrid several years ago, but was thrilled to see the way the National Gallery displayed them. She pointed out how each room picked up cues from the costumes and backdrops to reinforce the overall effect. We watched every video, looked at every description. In the gift shop we picked out books about ballet and costumes for our granddaughters. To top off such a glorious morning we enjoyed a delicious lunch at Gallery’s Café Ballets Russes. Having had our ears and eyes so stimulated by the exhibit, we now tasted Russian favorites as interpreted by Chef Michel Richard, complete with take-home recipe cards.

Leave a Reply