Edinburgh 2017

History: In the wake of World War II, a group of visionaries pondered the future for European artists and audiences. One of those visionaries was Rudolf Bing, an Austrian who had fled Hitler, become a British citizen, and later became General Manager of the Metropolitan Opera. Harvey Wood, another member of the group, recorded how the Edinburgh International Festival was founded to “provide a platform for the flowering of the human spirit.”:

The Edinburgh International Festival was first discussed over a lunch table in a restaurant in London, towards the end of 1944. Rudolf Bing, convinced that musical and operatic festivals on anything like the pre-war scale were unlikely to be held in any of the shattered and impoverished centres for many years to come, was anxious to investigate the possibility of staging such a Festival somewhere in the United Kingdom in the summer of 1946. He convinced my colleagues that such an enterprise, successfully conducted, might at this moment of European time, be of more than temporary significance and might establish in Britain a centre of world resort for lovers of music, drama, opera, ballet and the graphic arts.

Certain preconditions were obviously required: it should be a town of reasonable size, capable of absorbing and entertaining between 50,000 and 150,000 visitors for up to a month. It should, like Salzburg, have considerable scenic appeal and it should be set in a country likely to be attractive to tourists and foreign visitors. It should have sufficient number of theatres, concert halls and open spaces for the adequate staging of a programme of an ambitious and varied character. Above all it should be a city likely to embrace the opportunity and willing to make the festival a major preoccupation in the heart of every citizen. Greatly daring but not without confidence, I recommended Edinburgh as the centre and promised to make preliminary investigations

The idea took hold! The arts have flourished and are flourishing! Ten other festivals, collectively, the Edinburgh Festival, are now held every summer. The Edinburgh Fringe, which started as an offshoot of the International Festival, has since grown to be the world’s largest arts festival with hundreds of events each day. Every year, there are eight tourists who visit the city for every resident.

The idea took hold! The arts have flourished and are flourishing! Ten other festivals, collectively, the Edinburgh Festival, are now held every summer. The Edinburgh Fringe, which started as an offshoot of the International Festival, has since grown to be the world’s largest arts festival with hundreds of events each day. Every year, there are eight tourists who visit the city for every resident.

Steve and I enjoyed concerts and Fringe events most summers from 2004 to 2012, once with David and Leslie, and other times with the Rennies and the Pitkins. In 2015, Anne Rennie took me to the Art Festival at Jupiter Artland. This year Elizabeth and Jan Lodal flew in from France for their first visit to Scotland. In addition to Festival events, I got to introduce them to the literary heroes Scotland holds dear. We had breakfast at The Conan Doyle, a pub near the birthplace of the creator of Sherlock Holmes. We identified the Robert Burns Monument on Calton Hill and the monument to Walter Scott on Princes Street. In 2004 Edinburgh was named the first UNESCO City of Literature.

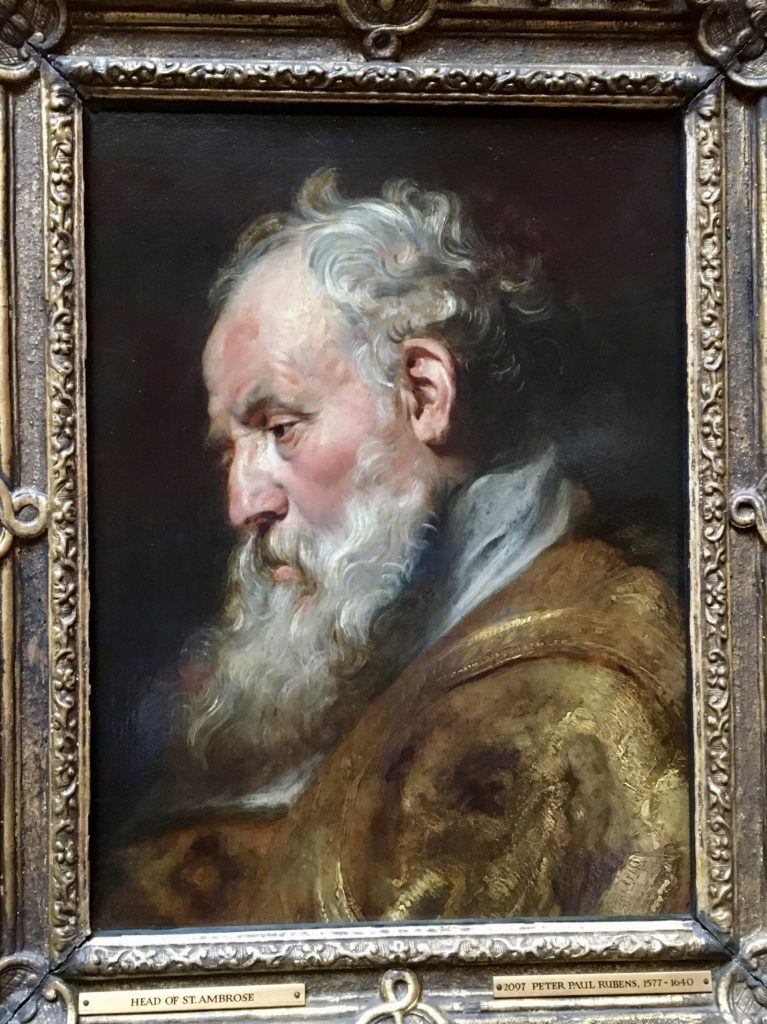

Art: For an overview of the city, Elizabeth and I hopped on a double-decker sightseeing bus. We hopped off at the National Gallery of Scotland, where Jan met us for lunch. It was fun to see what attracted my friends’ attention. Jan marveled at these two paintings:

While Elizabeth, former high school principal, zeroed in on this one:

I, on the other hand, stopped to look at paintings with musical subjects:

We all admired Canaletto’s views of Venice

The Gallery and the National Museum were so full of treasures, that I later spent a whole day editing and identifying these two photo albums, National Gallery of Scotland and National Museum of Scotland. [click on Info for identifications]

Music: The Royal Edinburgh Military Tattoo on Friday evening was perfect for three people who had played (or, in Elizabeth’s case, twirled) in Texas high school marching bands. Besides, when Jan finished his work as Deputy Under Secretary of Defense for Policy in the mid-90s, Steve and I had attended a tattoo in his honor at the Marine Corps barracks in Washington. At dinner before the Tattoo at the Cannonball Restaurant, we met the charming Jensen family from Norway, who were also on their way to the Tattoo. Their son Amund would be an ideal pen pal for our grandson Stephen. With the marvelous backdrop of the Edinburgh Castle, this Tattoo showcased bands from Monaco, France, India, the US, and Japan, as well as the Massed Bands of Her Majesty’s Royal Marines, and many Scottish singers and dancers. I loved hearing the Japanese soprano belt out “Skye Boat Song.” At the end we all sang “Auld Lang Syne” and the bands marched out to “Scotland the Brave.” A wee bit of rain fell, but we stayed warm and dry.

The opening concert on Saturday featured the Edinburgh Festival Chorus, directed by Christopher Bell, whom the Washington Chorus had recently recruited to become their next Director. Elizabeth and Jan have supported the Washington Chorus for years and invited Christopher to join us for dinner.

The concert was an ideal blend of the familiar and the fresh. First was Joseph Haydn’s Symphony No. 94 in G Major, the “Surprise” symphony. Ever since my mother taught her piano students from John Thompson’s “Teaching Little Fingers to Play,” I had known a rhyme set to the first bars of the second movement that outline a major and a dominant seventh chord:

Papa Haydn’s dead and gone, but his memory lingers on.

When his mood was one of bliss, he wrote jolly tunes like this.

Then came a sudden loud fortissimo to wake everyone up! Surprise! I’d never really focused on the other three movements of this symphony, but found their rendition by the Scottish Chamber Orchestra to be throughly delightful. The conductor, Pablo Heras-Casado, was particularly energetic and effective.

The choral part of Mendelssohn’s Lobgesang Op. 52 (Symphony No. 2) comprises a greater proportion of this work than does the choral part in Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. Stephen Johnson’s excellent program notes related the background:

Composed to celebrate the 400th anniversary of the Gutenberg Press and based on the words of Martin Luther’s revolutionary translation of the Bible, Lobgesang is a celebration of two of the most important contributions to modern civilization by Protestant Germany… made at a time when there was no political entity called ‘Germany,’ only a loose confederation of duchies, principalities, and independent city-states.

The part most familiar to me was the famous Thanksgiving hymn, “Now Thank We All Our God,” or in German, “Nun danket alle Gott.” In the eighth of ten movements, when the 125-voice choir sang those words a cappella, my tears began to fall. Struggling as always to define the meaning of “God”, I realized that evening that God could simply be the personification of the ideals for which we who emulate Christ strive, a father-figure to pray to when those ideals are unmet or under threat. Felix Mendelssohn-Bertholdy is one of my favorite composers. This choir, so well-trained and so well-conducted, was beautifully conveying what I perceived as Mendelssohn’s faith in God, in Germany, in the Bible, in the printing press, and in music. I share that expressed faith.

On Sunday, we visited the High Kirk, the Mother Church of Scottish Presbyterianism, St. Giles Cathedral, where the Honorable Lord Provost of the City, the members of the City Council and representatives of the Edinburgh International Festival were honored guests. Two of the dignitaries wore bright red, tasseled robes with ermine collars; many men were in morning coats and top hats; ladies in fascinator hats. The choir and the organ were equally magnificent. The sermon by David Fergusson, Professor of Divinity, University of Edinburgh, appropriately quoted a Gaelic proverb: “The world may come to an end, but art and music will endure.” He went on to say that “art lifts us from the preoccupations of the material world to the contemplation of the eternal.” Those words confirmed my conception of God as the personification of our ideals. The Edinburgh Festival celebrates our striving for the best life has to offer.

Still to come was five hours of Wagner, so we had a lovely lunch and a nap before returning to Usher Hall at 5 o’clock for a concert presentation of Die Walküre* by the Royal Scottish National Orchestra. It was conducted by Andrew Davis, with Bryn Terfel as Wotan, Christine Goerke as Brunnhilde, Simon O’Neill as Siegmund, and Amber Wagner as Sieglinde. This is the same opera Jan and Elizabeth had taken me to see at the Met in 2010, but this performance lacked the sets and costumes. Nevertheless, the singing and acting were so superb that it was easy to imagine the visuals. And if Mendelssohn’s Lobgesang was a glimpse of God, then Wagner’s finale, with six harps and two piccolos, was a glimpse of Heaven. During those five hours I had the pleasure to sit by and, at intermissions, get acquainted with local Scots, Callum and Clare Hay. The next day they sent me a photo and this comment by Callum, who is a member of the Edinburgh Festival Chorus that we had heard the night before:

What a concert! In Edinburgh every performance is special (of course!) but every now and again one comes along that finds something extra, some magic spark that propels it forwards and something truly extraordinary happens. I think that happened on Sunday night, and we’re so glad we were there.

I, too, was glad to be in Edinburgh with friends of a half-century, to meet other music lovers, and to be part of an audience grateful for such uplifting presentations.

* Hugh Canning’s review of Die Walküre in The Sunday Times, August 13, 2017, is worth printing in full:

Die Walküre was touched by the Wagnerian Gods. Although he has already conducted the Ring at Lyric Opera of Chicago and is forging a new one with Welsh National Opera’s David Pountney for 2020, Andrew Davis is not yet known in the UK as a Wagnerian. His meticulous preparation of the Royal Scottish National Opera, playing at a level I don’t think I have encountered before, ensured a performance of high drama but also countless moments of repose, when the players revelled in Wagner’s writing for wind and brass.

Reginald Goodall always used to stress the importance of the bass trumpet part in the Ring, and here Emma Bassett, with her immaculate breath control and coppery tone, deserved star billing, even if her limelight was stolen by Cillian O’Ceallachain’s rasping stierhorn, as Hunding and his henchmen closed in on Siegmund. Davis masterminded an almost scenic presentation of Wagner’s orchestra, with six harps vividly evoking the flicker of Loge’s flames as Wotan surrounds the sleeping Valkyrie with a circle of fire.

And his top-notch international cast sang as if ablaze. Bryn Terfel’s Wotan is familiar from Covent Garden and the Proms, but I don’t remember him singing in such resonant voice and with such dramatic involvement before. His world-weariness as he contemplates the Twilight of the Gods in his long narration to Brünnhilde in Act II — has he ever sung Das Ende! Das Ende! with such tragic potency before? — hardly prepared us for his incandescent rage when she disobeys his orders, or his tenderness at their parting in his magisterial Farewell.

The American soprano Christine Goerke surpassed all expectations with her fearless, radiantly sung Brünnhilde, her first here, and brought with her an even more impressive Sieglinde in the UK debutante Amber Wagner, whose huge, luscious tone, excellent diction and generous phrasing make her an ideal vocal exponent of the role. I’m not sure I have heard better. A starry team of Valkyries and Karen Cargill’s majestic Fricka, unpicking Wotan’s dubious self-justifying arguments with forensic emphasis, completed this exceptional cast of ladies.

Simon O’Neill’s heroically sung Siegmund, perhaps a little taxed by the low-lying Annunciation of Death scene, and Matthew Rose’s dark, baleful Hunding shared in their triumph, and in a thunderous ovation at the Usher Hall, almost certainly the loudest and longest I have heard there.

Leave a Reply