Frederick Douglass

The December 1 New York Times spotlighted an exhibit on Frederick Douglass at the Savannah College of Art and Design Museum of Art. Five days later Steve and I stopped in Savannah on the way from one golf tournament in Sea Island GA to another in Beaufort SC. We spent a fascinating two hours at Frederick Douglass: Embers of Freedom, centered on the Douglass Family Archive from the collection of Walter and Linda Evans. The Archive’s fragile papers are now being digitized and will not be publicly exhibited again.

Two days later I took my friends Allene, Kate, and Nina back to Savannah to see this exhibit. They, too, were impressed by both Douglass and the Museum. I decided to become a Museum Member, in order to visit again next April when we come to the Savannah Music Festival.

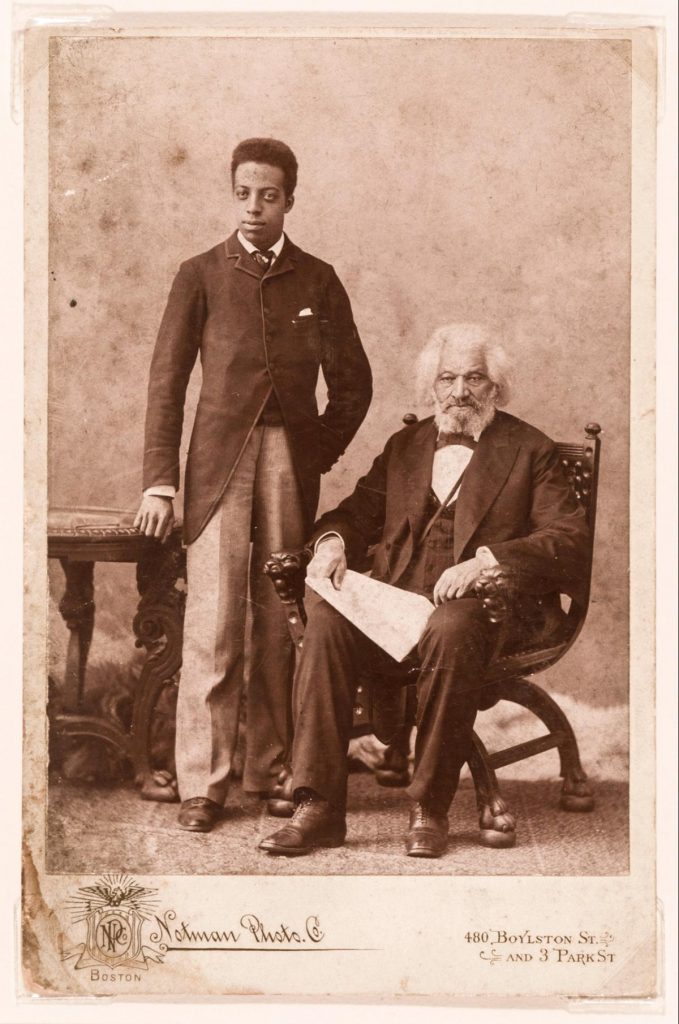

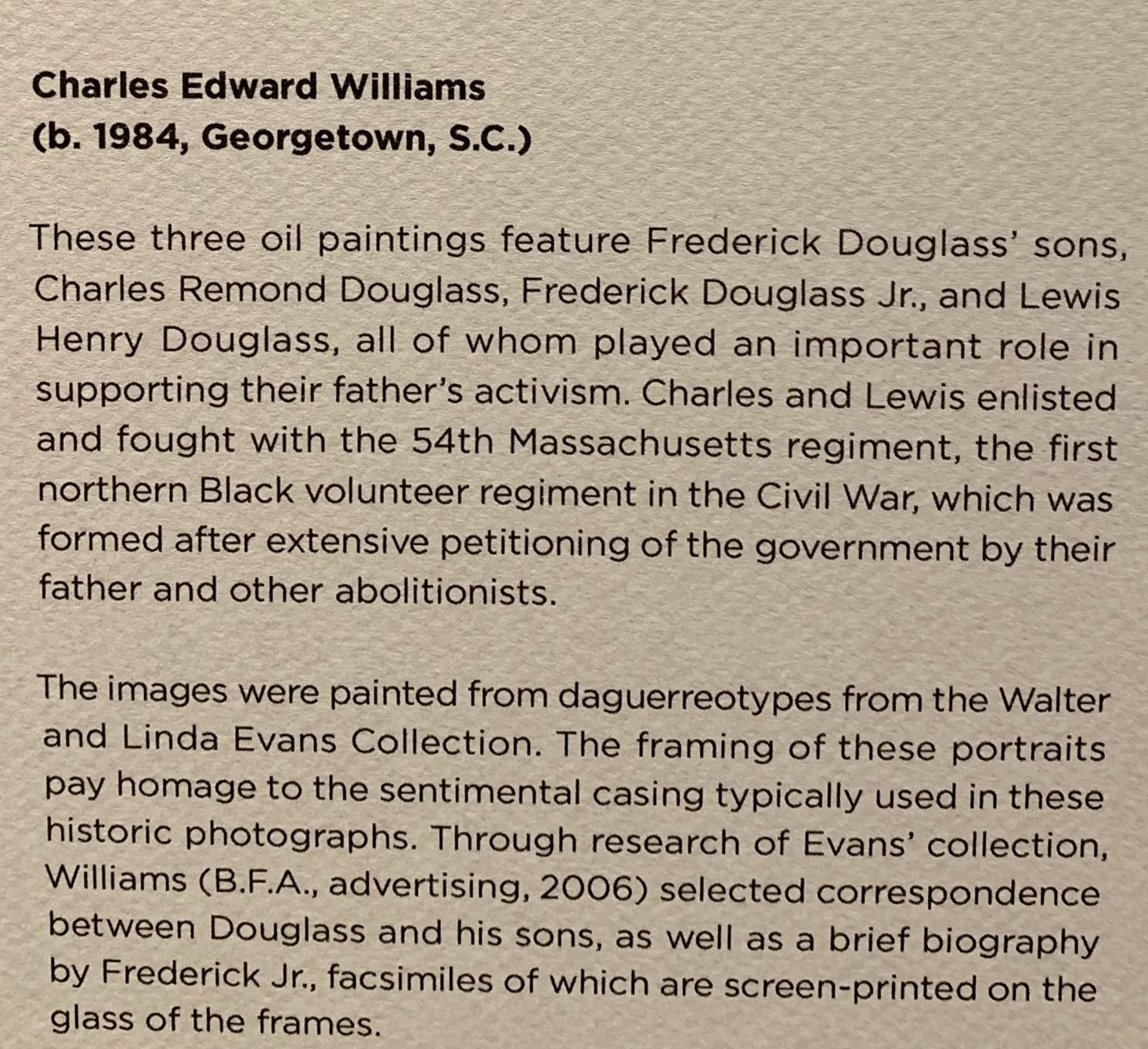

One of the key issues revealed in the Archive is the value of family. SCADMoA commissioned five contemporary artists to contribute their interpretations and drew on the museum’s collection to encourage viewers to think more deeply about Douglass’s family and Black families today. Charles Edward Williams, a native of South Carolina who had earned a B.F.A, in advertising from SCAD in 2006, used his commission to paint oil portraits of Douglass’s three sons. What you can barely see etched on the glass covers are fragments of correspondence between father and sons. Charles and Lewis fought with the 54th Massachusetts regiment, the first northern black volunteer regiment in the Civil War.

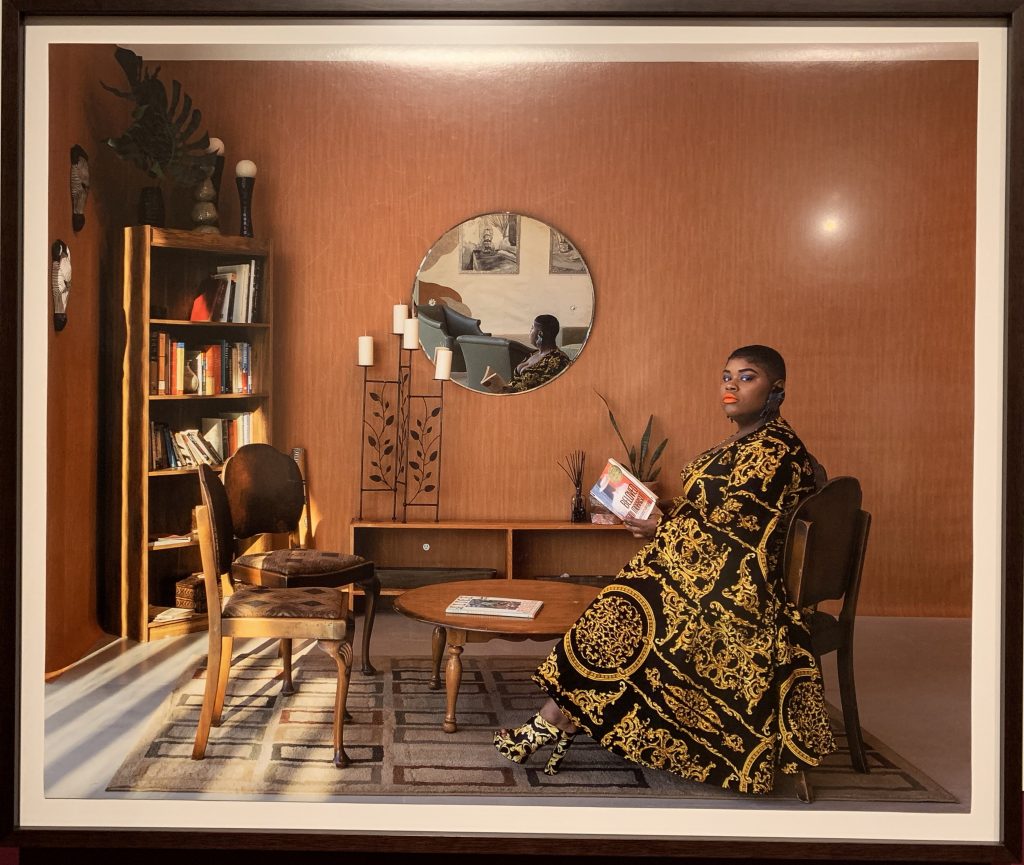

Glyneisha Johnson titled her commission “Herstory,” imagining what her living space could convey about her heritage and her personality.

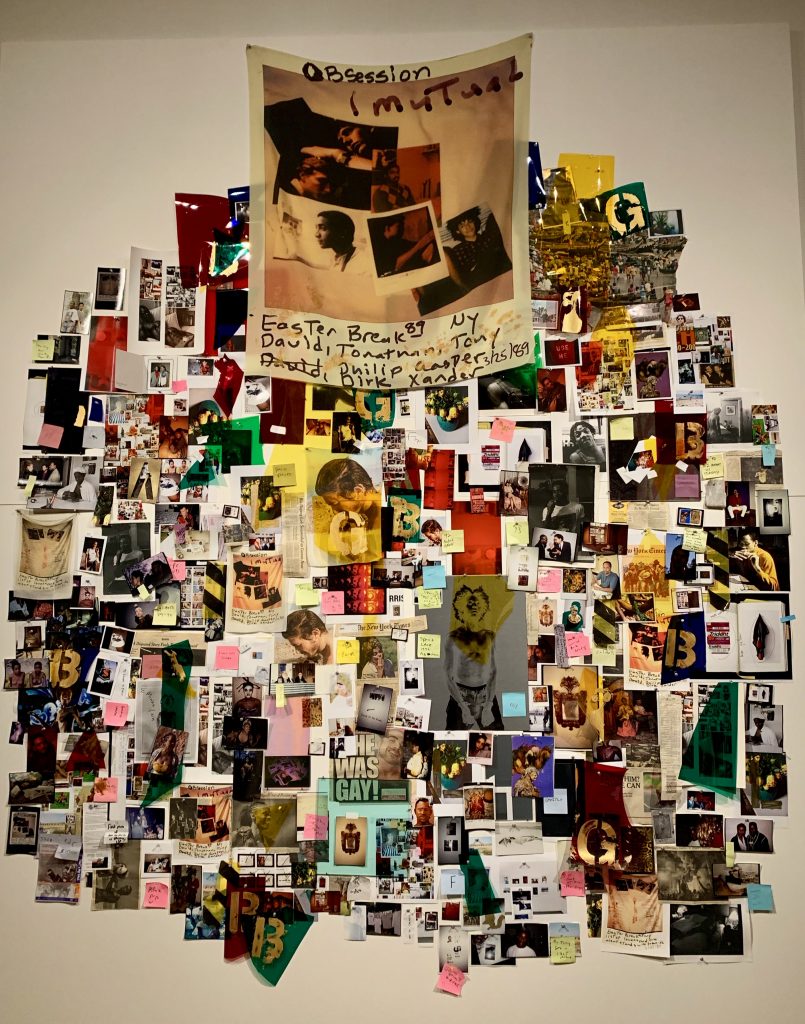

Steve was intrigued by Obsession, a work by Lyle Ashton Harris that the Museum acquired.

A 2015 painting by Tanzanian artist, Lubaina Himid, Portrait of Frederick Douglass’ Lapels, resonated with me. Douglass’s first wife Anna, the mother of his children, took special care of his clothes so that he would always look his best when giving speeches to Abolitionists. She even sent fresh shirts ahead to his next stop!

It was the 30-minute film by Isaac Julien, The North Star: Lessons of the Hour, that we liked best of all. It showed different perspectives of Douglass’ life projected on five screens simultaneously. Isaac Julien, both director and actor, effectively captured Douglass’s imposing presence and his enormous impact. He made the images and texts in the Archive come alive with actors listening to Douglass’s powerful words.

It was the 30-minute film by Isaac Julien, The North Star: Lessons of the Hour, that we liked best of all. It showed different perspectives of Douglass’ life projected on five screens simultaneously. Isaac Julien, both director and actor, effectively captured Douglass’s imposing presence and his enormous impact. He made the images and texts in the Archive come alive with actors listening to Douglass’s powerful words.

Less entrancing was The Golden March by Raphaël Barontini, presented in the three “jewel boxes” on the outside of the museum. They were packed with information, but the meaning was hard to grasp.

Beaufort SC hosted a Gullah festival while we were in town. While we ate shrimp and grits, we listened to this wonderful Gullah choir. I danced with two of them when they mingled with the audience.

Then we examined craft items by both Low Country and African artists. Allene bought a Gullah figure and I, a fan made in Ghana. These will be tangible reminders of the rich cultural heritage the Douglass exhibit inspired us to access.

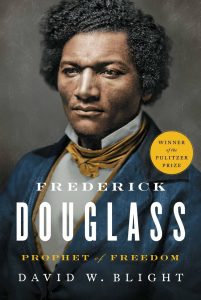

In the museum shop, I bought this new biography by Yale historian David W. Blight, Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom, which won a 2019 Pulitzer Prize. Just a few chapters in, I’ve already learned that Douglass was born in 1818 in southern Maryland, not far from where Harriet Tubman was born four years later, that he studied the same book on oratory that Abraham Lincoln used, and that he was the most photographed man in the 19th century. I look forward to reading all 761 pages of this book. Just a month ago, Steve and I saw the wonderful movie, Harriet. Now, having seen this exhibit, begun this book, and experienced Low Country culture, I want to know more about Douglass, whose house in Washington DC I visited many years ago with my friend Judith Morris.

In the museum shop, I bought this new biography by Yale historian David W. Blight, Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom, which won a 2019 Pulitzer Prize. Just a few chapters in, I’ve already learned that Douglass was born in 1818 in southern Maryland, not far from where Harriet Tubman was born four years later, that he studied the same book on oratory that Abraham Lincoln used, and that he was the most photographed man in the 19th century. I look forward to reading all 761 pages of this book. Just a month ago, Steve and I saw the wonderful movie, Harriet. Now, having seen this exhibit, begun this book, and experienced Low Country culture, I want to know more about Douglass, whose house in Washington DC I visited many years ago with my friend Judith Morris.

Leave a Reply