Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo da Vinci, Walter Isaacson’s marvelous biography of the genius who died 500 years ago, is like a seven-course dinner that must be consumed slowly. It has taken me several months to savor and digest 30 of the 33 chapters. I look forward to returning to the ones on anatomy and hydraulics when I’m really hungry.

Leonardo da Vinci, Walter Isaacson’s marvelous biography of the genius who died 500 years ago, is like a seven-course dinner that must be consumed slowly. It has taken me several months to savor and digest 30 of the 33 chapters. I look forward to returning to the ones on anatomy and hydraulics when I’m really hungry.

The book provided the pleasure of recalling my own encounters with Leonardo: seeing Portrait of Ginevra de’ Benci at the National Gallery in DC, the Mona Lisa at the Louvre, and watching Steve in a re-enactment of The Last Supper at Cherrydale Methodist Church in 1978. Just last month, Lilli, Violet and I saw a collection of Leonardo’s drawings at Buckingham Palace.

Isaacson begins with a helpful timeline relating Leonardo’s work with world events. He was born in 1452, not long after Gutenberg printed the Bible. In his twenties, Leonardo began to collect books of his own. Michelangelo was born in 1475, about the time Leonardo began Portrait of Ginevra de’ Benci. In 1493, when Columbus had arrived in the West Indies, Leonardo’s enormous clay model for a horse monument was put on display in Milan. The Last Supper was painted in the refectory of a convent in Milan in 1495. In 1500 Leonardo returned to Florence and began painting the Mona Lisa and worked on it for the rest of his life.

The Mona Lisa, Isaacson says, is the culmination of “a life spent perfecting an ability to stand at the intersection of art and nature.”

What began as a portrait of a silk merchant’s young wife became a quest to portray the complexities of human emotion, made memorable through the mysteries of a hinted smile, and to connect our nature to that of our universe. The landscape of her soul and of nature’s soul are intertwined.

Isaacson describes The Last Supper as a moment in motion:

Leonardo’s painting depicts the reactions just after Jesus tells his assembled apostles, “One of you will betray me.”…The picture vibrates with Leonardo’s understanding that no moment is discrete, self-contained, frozen, delineated, just as no boundary in nature is sharply delineated. As with the river that Leonardo described, each moment is part of what just passed and what is about to come. This is one of the essences of Leonardo’s art: from the Adoration of the Magi to Lady with an Ermine to The Last Supper and the Mona Lisa, each moment is not distinct but instead contains connections to a narrative.

I hadn’t understood that important point before. Now I want to go back and look at those treasures again and again. While those two quotes give you an idea of the scope and depth of this biography, there’s so much more. There’s an account of how Leonardo’s Florence studio combined individual genius with teamwork.There are a few paragraphs on how Leonardo’s personality contrasted with Michelangelo’s and why they didn’t get along. There’s Leonardo’s dedication to his anatomy studies: “from 1508 to 1513, he seemed never to tire of it and kept digging deeper, even though it meant nights spent amid cadavers and the stench of decaying organs. He was mainly motivated by his own curiosity.”

There’s more on Leonardo’s studies of the flight of birds and how he dreamed of making a flying machine; more on his expertise in painting perspectives, more on how branching rivers are a metaphor for the microcosm-macrocosm relationship.

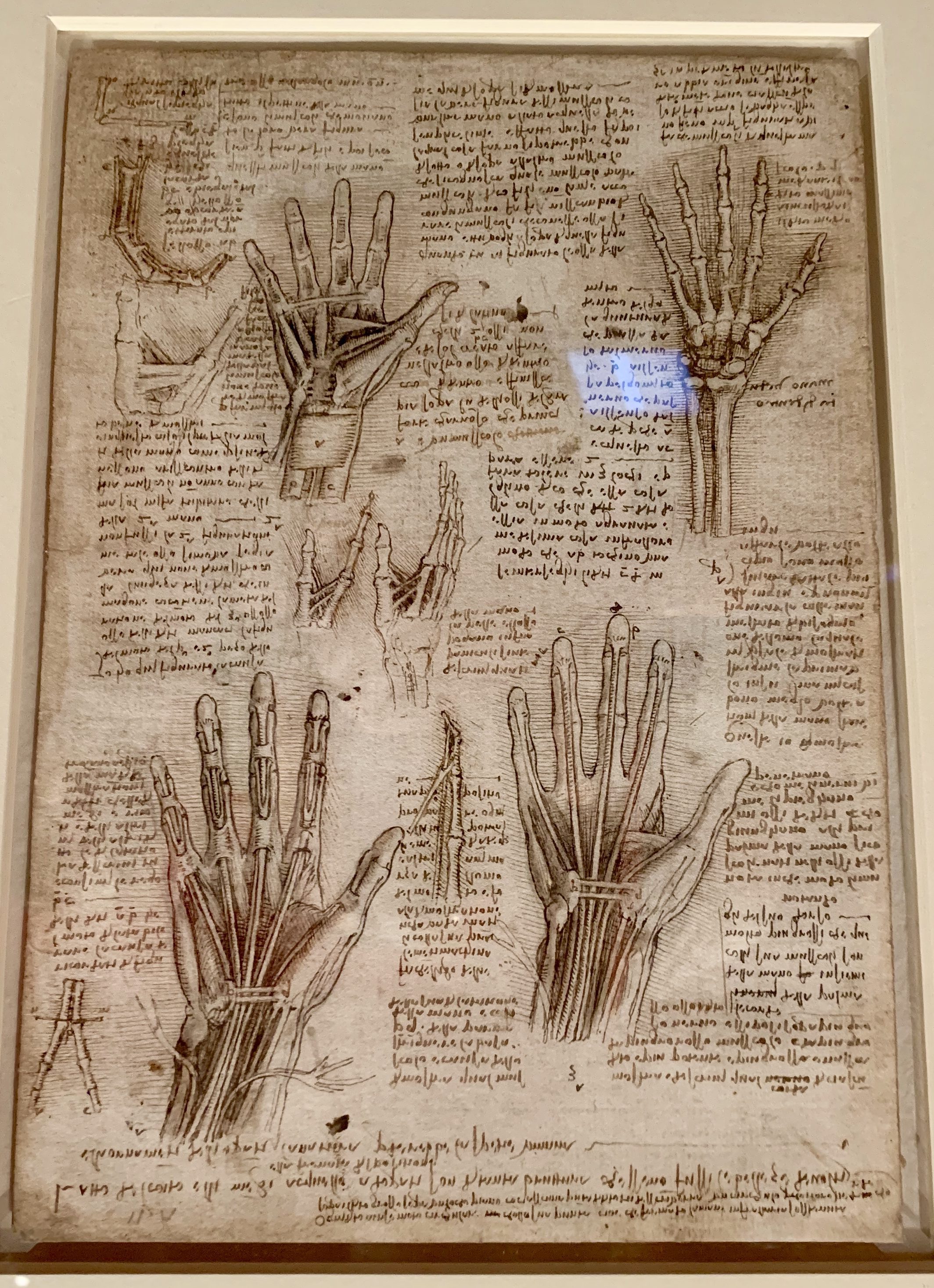

Since as a pianist, I must use my hands with both precision and delicacy, I look forward to studying Leonardo’s drawings of hands, which I photographed in London. He had dissected their muscles, tendons, and bones and drew them accurately. He knew intimately how to portray gestures.

Isaacson reminds us that one of Leonardo’s first jobs was that of Court Entertainer, a producer of pageants for the court of Ludovico Sforza in Milan. I kept thinking my niece Patti’s husband, Scott Osborne, in Dallas. He would love this book; it might give him ideas for the theater classes he teaches and the set designs he creates .

I also thought of my friend Suzanne Guy, who wrote The Music Box: the Story of Cristofori. In one of his many notebooks Leonardo drew

a mechanized ringing instrument composed of a stationary metal bell flanked by two hammers and four dampers on levers that could be operated by keys to touch the bell at different places. Leonardo knew that a bell has different areas that, depending on their shape and thickness, produce different tones. By dampening up to four of these in different combinations, he could turn a bell into a keyboard instrument that played a variety of pitches.

It would be another 200 years before Cristofori, another Florentine, invented an instrument that used hammers and strings, my beloved pianoforte. It would be another 400 years before the Wright Brothers figured out flying machines. Thank you, Walter Isaacson, for setting an exquisite table and inviting me to dine with Leonardo, a man far ahead of his time.

Here’s a song from the 1950s that keeps going through my head. Nat King Cole, too, had a certain genius.

Leave a Reply