Martin Luther King, Jr.

Last Friday evening Leslie, David and I attended an hour-long jazz tribute to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. by Zach Bartholomew’s Trio at the Coral Gables Congregational Church, where my granddaughters attend preschool. The Trio, based at the University of Miami, played music by or associated with Canadian jazz great Oscar Peterson (1925 – 2007), beginning, appropriately, with Peterson’s arrangement of Georgia on My Mind. It brought the King Center in Atlanta to my mind. Peterson received the first Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Achievement Award from Canada’s Black Theatre Workshop in 1986. Sherrie Mostin, guest vocalist, sang Peterson’s Hymn to Freedom:

When every heart joins every heart and together yearns for liberty,

That’s when we’ll be free.

When every hand joins every hand and together moulds our destiny,

That’s when we’ll be free.

Any hour any day, the time soon will come when men will live in dignity,

That’s when we’ll be free.

When every man joins in our song and together singing harmony,

That’s when we’ll be free.

A large, diverse crowd stood and clapped along to the hymn. It was a moving experience that made me want to make my own tribute to King. That feeling was reinforced the next morning when my book group met to discuss a terrific novel, Someone Knows My Name, by Lawrence Hill, who is Canadian. This book taught us a lot about slavery–what it would be like to be a child in Mali in 1757, to see one’s parents killed, to be captured and bound in chains, to be marched overland to the west coast of Africa and loaded on a British slave ship bound for South Carolina. Aminata was smart and strong. She made the most of the positive attitudes and abilities her parents had imprinted. At age eleven, she could speak two tribal languages, read the Qu’ran and write in Arabic, deliver babies, and plant crops. These skills helped her to survive the two-month journey across the Atlantic and several years on an indigo plantation.

Amanita married a man from her country, but her first baby was taken from her when he was ten months old and sold. She never saw him again. Just imagine! Then she, too, was sold to a Charleston indigo inspector who had spotted her abilities on the plantation where she worked. Solomon Lindo, who was Jewish, taught her to keep books and later took her to New York City, where she remained throughout the Revolutionary War. White Americans won freedom from the British, but Black Americans did not. After the war Aminata was given the task of recording in The Book of Negroes (the Canadian title of the novel), the names of over 3000 Blacks who had been loyal to Britain and were therefore eligible to relocate to Nova Scotia, where they enjoyed more personal freedom, but the same economic hardship. After several years in Canada, she went on to Sierra Leone and finally to London with British Abolitionists. Every step of her journey was remarkable and convincing. Hill’s achievement in imagining such a woman is stunning. Reading and discussing this book was, indeed, a tribute to Dr. King.

The West African setting of the opening of Hill’s novel is similar to that of Yaa Gyasi’s Homegoing, a 2016 Best Seller that portrays two strong African women and their descendants. One woman married a British soldier and stayed in Africa, while the other, like Aminata, was shipped to America. My first reading left me fascinated, but confused by the seven generation span. I look forward to reading it again. Both novels make clear how little outsiders knew about Africa and how much those who were sent away yearned to return.

Another recent musical experience made me delve more deeply into the origins of slavery. On January 7, my friend Rosemary and I watched the Metropolitan Opera production (live in HD at our local theater) of Nabucco, by Giuseppe Verdi, with Placido Domingo in the title role. Our community chorus had sung the famous Chorus of the Hebrew Slaves “Va, Pensiero,” a few years ago; it was thrilling to hear it done by the Met chorus. Here’s a short clip.

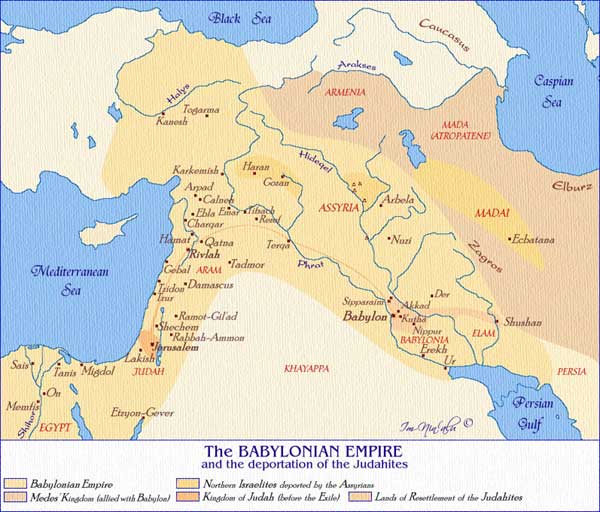

Nabucco is Italian for Nebuchadnezzar, the king of Babylon, who besieged Jerusalem in 606 BCE, took the Hebrews captive, and eventually destroyed their temple. I found the story in the Old Testament Book of Daniel. This map shows ancient Babylon, now Baghdad, in an area familiar from the evening news.

The opera inspired me to do more research about the history of slavery. According to this timeline of slavery, slavery dates back to at least 3000 BCE, when imperial armies captured their enemies and made them slaves. The Code of Hammurabi, c. 1720 BC, is the first surviving document to record a law relating to slaves. That’s about the same time that the Bible tells of Hebrew slaves in Egypt. Slavery flourished in the Roman Empire. In a book I’ve been reading chapter by chapter, The Silk Roads: a New History of the World, Peter Frankopan asserts that “at the height of its power, the Roman Empire required 250,00 – 400,00 new slaves each year to maintain the slave population.”

Slavery still exists in the Middle East. ISIS recently released a pamphlet on how female sex slaves were to be treated. Sex trafficking continues now throughout the world. Check out Walk Free’s website for the dimensions of this modern scourge. Therefore, another tribute I can pay to Dr. King is to learn more about slavery and find out what I can to do to stop it. Let me know your thoughts.

Leave a Reply