Welcome to Ohio

Just as runaway slaves in the mid-1800s found refuge in Ohio, I found a warm welcome and relief from Florida heat with my friend Marjo last week. On Thursday she picked me up at the Cincinnati airport, which is actually in Kentucky. After lunch in charming Burlington we crossed the Ohio River on the Anderson Ferry to Cincinnati. Before levees were built, the river was wider and shallower. Slaves could wade across in August or walk across in January when the river froze. Now more narrow, it is deep enough for long coal barges like the one that stretches across the distant shore in this photo.

Just as runaway slaves in the mid-1800s found refuge in Ohio, I found a warm welcome and relief from Florida heat with my friend Marjo last week. On Thursday she picked me up at the Cincinnati airport, which is actually in Kentucky. After lunch in charming Burlington we crossed the Ohio River on the Anderson Ferry to Cincinnati. Before levees were built, the river was wider and shallower. Slaves could wade across in August or walk across in January when the river froze. Now more narrow, it is deep enough for long coal barges like the one that stretches across the distant shore in this photo.

Aware of my recent study of Black history, Marjo took me directly to the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center. It was built in 2004 on the riverfront, midway between a stadium where the Cincinnati Reds play baseball and another where the Bengals play football. There were few visitors, all masked; we practically had the place to ourselves.

For enslaved people the Ohio River was more than the natural border between free and slave states; it was the “River Jordan” for their Exodus. Crossing it was a huge step on the path to freedom. Northerners opposed to slavery set up a network of safe houses to assist escaped slaves seeking freedom. These were “stations” on the Underground Railroad.

The museum features a reconstructed slave pen recovered from a farm in Mason County, Kentucky. The structure was used as a holding pen by slave trader Captain John W. Anderson (apparently the same person whose name is on the ferry we took). It was a holding pen for enslaved people before they were marched more than 750 miles and sold at the auction block in Natchez, Mississippi.

Walking into this pen, we saw posters instructing us to keep 6 feet apart. Hah! Slaves never had the luxury of social distancing; a hundred or more sometimes occupied this space. Strong hooks in the ceiling and the walls anchored the chains binding slaves. I could feel the pain of slavery in my whole body.

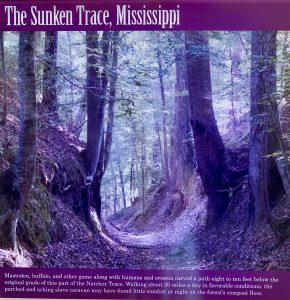

This poster reminded me that “send you to Natchez” was the ultimate threat to slaves in The Water Dancer, a novel by Ta-Nehisi Coates I read recently. During Easter vacation from Rice in 1963, my roommate Carolyn and I enjoyed a weekend adventure at Vanderbilt and then traveled the Natchez Trace Parkway from Nashville through Mississippi on our way back to Houston. I had never connected that lovely, spring flower-lined roadway with slaves being marched to market. I’m discovering more and more places that have underlying stories of which I have been unaware.

This poster reminded me that “send you to Natchez” was the ultimate threat to slaves in The Water Dancer, a novel by Ta-Nehisi Coates I read recently. During Easter vacation from Rice in 1963, my roommate Carolyn and I enjoyed a weekend adventure at Vanderbilt and then traveled the Natchez Trace Parkway from Nashville through Mississippi on our way back to Houston. I had never connected that lovely, spring flower-lined roadway with slaves being marched to market. I’m discovering more and more places that have underlying stories of which I have been unaware.

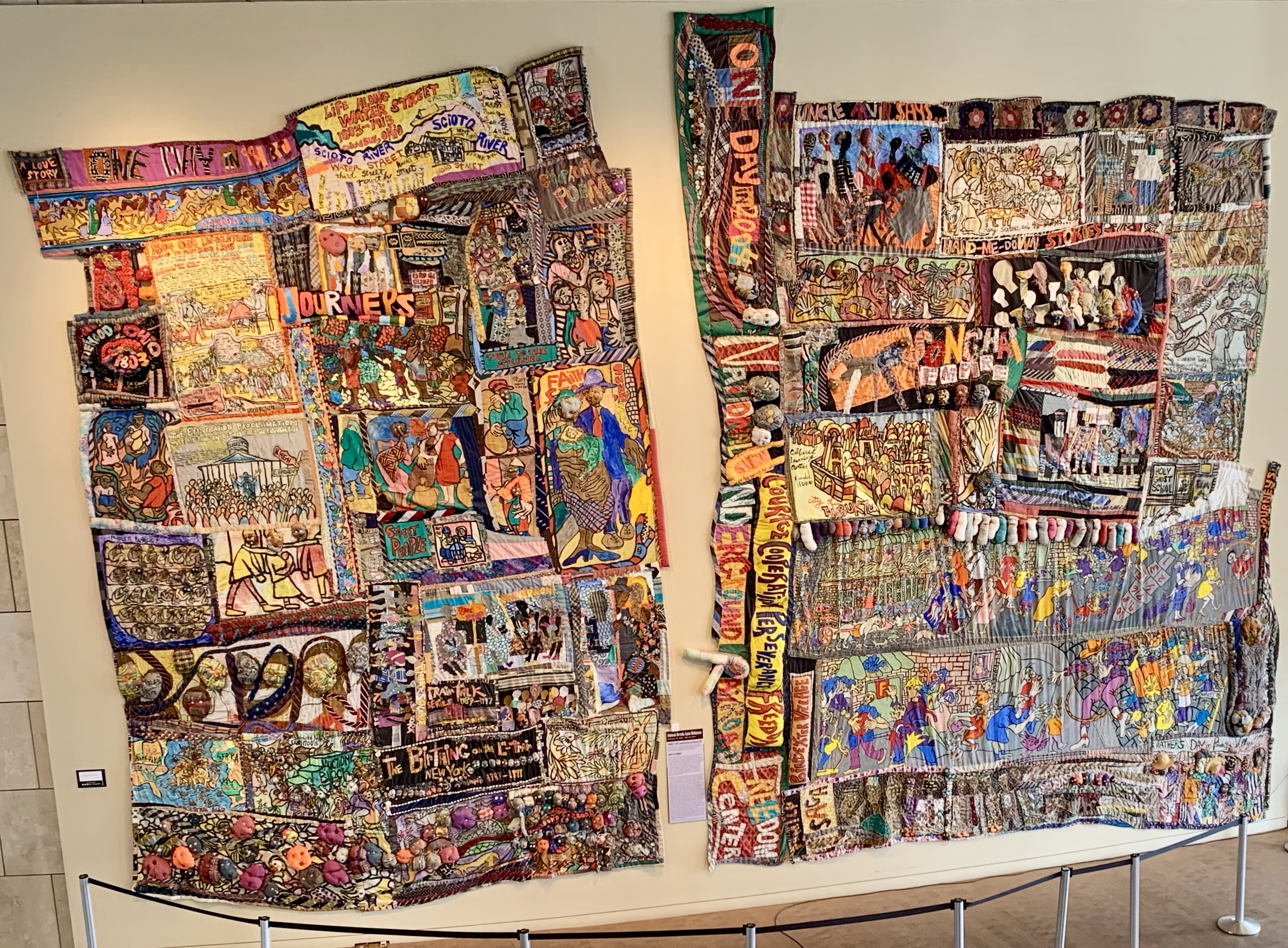

For example, I had heard that quilts made by people along the Underground Railroad often carried pictorial messages that runaways could easily decipher. But I had never seen two-story high quilts like these on display at the Freedom Center, both created by the same artist.

Aminah Brenda Lynn Robinson calls her creations raggonnon or “rag gon non.” She says the stories weave and rag in and out of history from the past to the present, hopefully touching and inspiring the lives of future generations. This is Aminah’s story and it took her thirty-five years to complete. On the left is Journey I, her family story from Angola, Africa to Columbus, Ohio. It includes depictions of slavery and her internship in New York, ending with 9-11-2001. Journey II, on the right, explores her Uncle Alvin’s stories about West Africa and Poindexter Village in Columbus, where she was born. This raggonnon includes 35 music boxes and a row of socks, each holding a story and healing herbs. For many raggonnon close-ups and other photos I took in this museum, please see this album.

Casey Jolley, director of Visitor Services, was at the front desk as we were about to depart. She and I compared this museum to the National Museum of African American History and Culture in DC, which she had also visited. Both were huge investments. She told us that Procter & Gamble, an important business presence in Cincinnati, had strongly supported the conception and construction of this museum. At the Gift Shop, I bought a dashiki that you can see me wearing as I play Nimble Feet by Florence Price.

Casey Jolley, director of Visitor Services, was at the front desk as we were about to depart. She and I compared this museum to the National Museum of African American History and Culture in DC, which she had also visited. Both were huge investments. She told us that Procter & Gamble, an important business presence in Cincinnati, had strongly supported the conception and construction of this museum. At the Gift Shop, I bought a dashiki that you can see me wearing as I play Nimble Feet by Florence Price.

To show me more about how welcoming Ohio had been to Blacks, Marjo drove the next morning to the National Afro-American Museum and Cultural Center. It is in Wilberforce, a town named after the British politician William Wilberforce, whose efforts led to the passage of Britain’s Slavery Abolition Act of 1833. Ohio abolitionists and religious leaders didn’t just shelter slaves, they set up education and training programs to give escapees opportunities to succeed. Two such institutions are still going strong in Wilberforce.

Wilberforce University was first. In 1851 a white entrepreneur, Elias Drake, opened a health resort on the site of five mineral-rich waterways once used by the Shawnee. This area became known as Xenia Springs and Tawawa Springs. The hotel accommodated a contentious mix of visitors: abolitionist Quakers, white and Black elite from Cincinnati, and Southern planters who brought with them enslaved Black women. While the springs promised rejuvenation, Black women often became pregnant.

Wilberforce University was first. In 1851 a white entrepreneur, Elias Drake, opened a health resort on the site of five mineral-rich waterways once used by the Shawnee. This area became known as Xenia Springs and Tawawa Springs. The hotel accommodated a contentious mix of visitors: abolitionist Quakers, white and Black elite from Cincinnati, and Southern planters who brought with them enslaved Black women. While the springs promised rejuvenation, Black women often became pregnant.

Many children conceived here returned when they came of school age. Tawawa House offered dormitories to those who were denied an education in the South. By 1856 the Cincinnati Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church purchased the property and converted it to a private university, the first of its kind for People of Color. While literacy for African Americans was still illegal in many states, free Black students, escapees on the Underground Railroad and the children of enslaved survivors and Southern oppressors all came to Wilberforce to learn.

Central State was founded in 1887 when the Ohio General Assembly established a state-funded vocational school as the Combined Normal and Industrial Department of Wilberforce University. It offered two years of training in a variety of fields including teaching. Fifty years later it was split off to separate state funding from the religious support of Wilberforce. By 1965 it became Central State University; in 2014 it was designated a Land Grant institution so that it could receive additional federal funding. The National Afro-American Museum and Cultural Center is at Central State University.

Central State was founded in 1887 when the Ohio General Assembly established a state-funded vocational school as the Combined Normal and Industrial Department of Wilberforce University. It offered two years of training in a variety of fields including teaching. Fifty years later it was split off to separate state funding from the religious support of Wilberforce. By 1965 it became Central State University; in 2014 it was designated a Land Grant institution so that it could receive additional federal funding. The National Afro-American Museum and Cultural Center is at Central State University.

This cultural center presented just the kind of immersion in Black history that I need. I took lots of photos, edited and labeled them, and divided them into two albums for you to inspect. Click here to learn about how Black men and women have been involved in major events from 1770 to the present and to become aware of the vital role Central State has played. Click here to learn how Black women have been activists for change in Ohio. I had hoped to see an exhibit like this somewhere for the 100th anniversary of Women’s Suffrage that I celebrated in August with my post, Women at Work. The Afro-American Museum did a great job of chronicling so many exemplary Ohio women–it made me feel welcome.

After that heady experience, we drove through fields of corn and soybeans to Yellow Springs, had lunch at Winds Cafe, bought some earrings, and came home to watch a movie, The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind–terrific! Four of Marjo’s friends, whom I had met in 2017, came over for drinks–what a wonderful day!

On Saturday we explored the Oregon District of Dayton and had brunch at Lily’s Bistro.

In the afternoon I had a chance to explore her neighborhood and the nearby Lincoln Park, before meeting her friend Ron for dinner. I saw an even mix of Biden and Trump signs, with both sides also displaying signs that said “Support the Police.” Lovely cool weather!

After such a stimulating three days, how did we spend our last day together? Sunday was the icing on our delicious cake! Marjo took me to St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Dayton, my first in-person worship in six months. Live music! Mark Hofeldt of the Dayton Philharmonic Orchestra playing a Bach unaccompanied Cello Suite and joining tenor Jimmy Leach and organist Lia Ferrell in César Franck’s Panis Angelicus. Tears of joy. Well-chosen and comforting words by The Reverend Dr. Daniel McClain. Sunlight streaming through stained glass. Prayers answered.

From church we drove to Cincinnati’s Taft Museum, Marjo’s favorite. The staff was extra friendly in welcoming visitors back safely. It was even free. Marjo was an excellent guide. Lunch on the outdoor patio was luxuriously relaxed. Again, I took lots of photos and enjoyed revisiting the museum virtually all week. An earlier owner of this house was Nicholas Longworth, who represented Ohio’s 1st District andserved as Speaker of the U.S. House 1925-31. The Longworth House Office Building in DC is named for him. His spouse was Alice Roosevelt, daughter of President Theodore Roosevelt. Here is a large album to view. It also includes photos of other buildings in the city that Marjo wanted me to see. THANK YOU, Marjo, my sister, for a superbly welcoming weekend! Love, Martha

Leave a Reply