Agents of Change

Over the last two years, I have become acquainted with brave women and men in earlier times who widened opportunities for all of us. Nathalia Holt’s Rise of the Rocket Girls (reviewed here), highlighted the work women did in the early days of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. The movie Hidden Figures celebrated women of color who worked for NASA. Recently I read two more books that illuminate how American women proved their value in astronomy and cryptology and brought change to academia and the armed services. I also saw a memorable exhibit about African American Agents of Change.

The Glass Universe: How the Ladies of the Harvard Observatory Took the Measure of the Stars, by Dava Sobel (2017) conveys the knowledge and skill women employed to fix the exact positions of thousands of stars in a worldwide stellar mapping project that began in the 1880s. Selina Bond, for example, came to work at Harvard’s Observatory every morning to apply mathematical formulae that corrected the previous night’s observations by male astronomers to account for the Earth’s progress in its annual orbit, the direction of its travel, and the wobble of its axis. Only later were women permitted to use the telescopes at night themselves. These human “computers” were a great bargain; they were paid $1500 per year, compared to $2500 for men. Though Harvard resisted granting them faculty positions, the Observatory hired more and more women. Several were attracted to astronomy by having viewed total solar eclipses.

The Glass Universe: How the Ladies of the Harvard Observatory Took the Measure of the Stars, by Dava Sobel (2017) conveys the knowledge and skill women employed to fix the exact positions of thousands of stars in a worldwide stellar mapping project that began in the 1880s. Selina Bond, for example, came to work at Harvard’s Observatory every morning to apply mathematical formulae that corrected the previous night’s observations by male astronomers to account for the Earth’s progress in its annual orbit, the direction of its travel, and the wobble of its axis. Only later were women permitted to use the telescopes at night themselves. These human “computers” were a great bargain; they were paid $1500 per year, compared to $2500 for men. Though Harvard resisted granting them faculty positions, the Observatory hired more and more women. Several were attracted to astronomy by having viewed total solar eclipses.

During her 40-year career with the Observatory, Dr. Annie Jump Cannon obtained and classified spectra for more than 225,000 stars, according to their temperature. Cannon also discovered some 300 variable stars and 5 novae. Though she was “recognized the world over as the greatest living expert in this line of work,” Harvard President Abbott Lawrence Lowell refused even to cite her name in the university catalogue, much less give her the title and pay many thought her due.

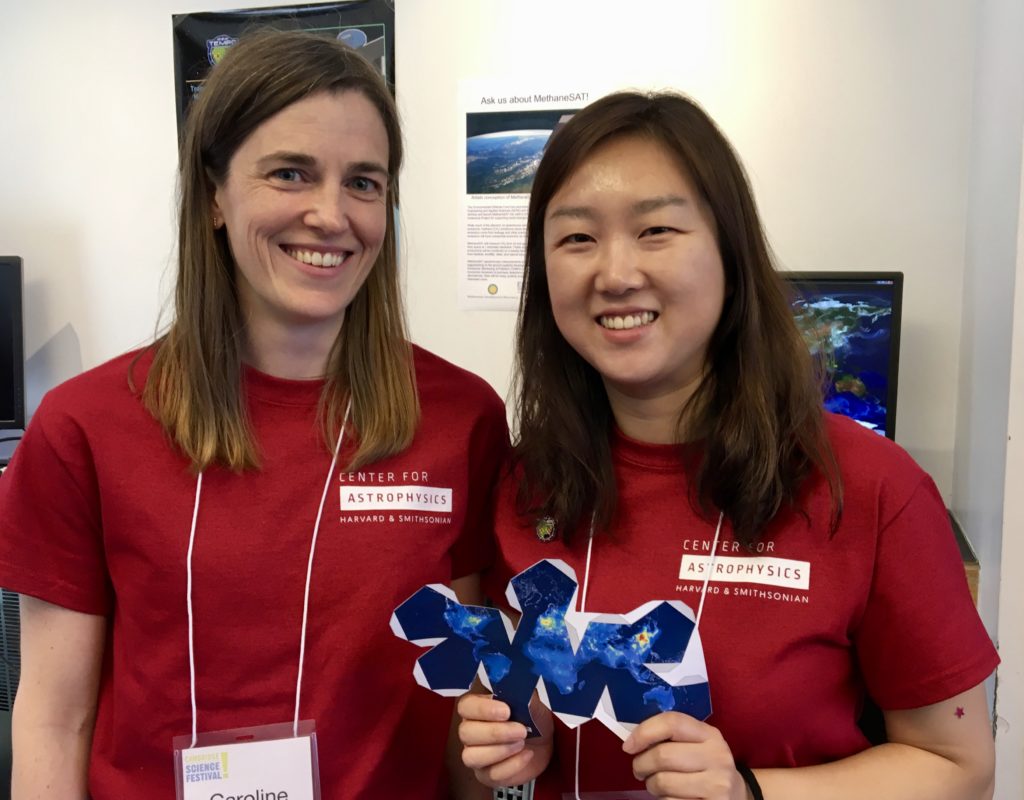

The Glass Universe was recommended to me by Dr. Caroline Nowlan, a scientist who monitors pollution in the earth’s atmosphere at Harvard’s Center for Astrophysics. I met her at the Cambridge Science Festival. Nowlan’s career and those of many other women are direct results of the trail blazed by the women featured in this book.

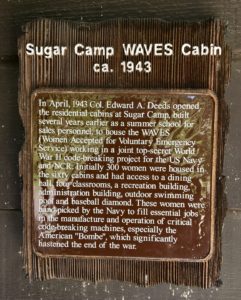

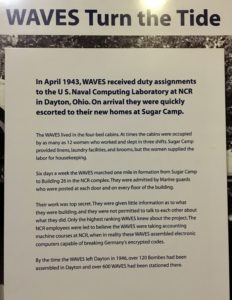

Angela Kerfoot lent me her copy of Code Girls: the Untold Story of the American Women Code Breakers of World War II by Liza Mundy (2017). I could hardly put it down. Not only was I familiar with the sites in DC and Arlington where the Navy and Army code girls worked, but also last September I visited Sugar Camp, in Dayton, Ohio, where WAVES worked in collaboration with National Cash Register (NCR) to break critical German codes.

Angela Kerfoot lent me her copy of Code Girls: the Untold Story of the American Women Code Breakers of World War II by Liza Mundy (2017). I could hardly put it down. Not only was I familiar with the sites in DC and Arlington where the Navy and Army code girls worked, but also last September I visited Sugar Camp, in Dayton, Ohio, where WAVES worked in collaboration with National Cash Register (NCR) to break critical German codes.

Soon after Pearl Harbor, Naval Intelligence officers contacted the presidents of elite Women’s Colleges for names of seniors like Frances Steen at Goucher, who “liked crossword puzzles and weren’t engaged to be married.” Army officers scoured Southern teachers colleges for apt women like Dot Braden of Lynchburg, Virginia. Working for the Army paid her almost twice as much as teaching sixty students in a rural schoolhouse. Along with thousands of others, these women played a critical role in speeding the end of the war. In addition to those cracking codes, an African American unit at Arlington Hall kept tabs on which companies were doing business with Hitler or Mitsubishi. Reading about the intense, secret work these women did in cramped spaces, under life-or-death pressures, made me feel so glad their full stories were being told at last.

At Steve’s Harvard Business School 50th Reunion, May 31 – June 3, 2018, we saw an exhibit at Baker Library celebrating Agents of Change: the Founding and Impact of the African American Student Union. When Student Union leaders asked why there weren’t more African Americans at Harvard, the Dean said, “Few have applied.” He then provided funds for two student leaders to travel to traditionally Black colleges during the summer of 1968; within a few years these efforts paid off. Harvard Business School now includes women and men from all around the world, as was vividly apparent as we observed more recent classes enjoying parallel reunions. One of Steve’s section mates speculated that gaining admission would likely be difficult for him now.

As I reported about the 45th Reunion, Steve’s class was overwhelmingly white males. This time we had dinner with one of the eight women in his class, Mary Liz Lewis, and her husband (and classmate) Jim Lewis. She told us two interesting facts: first, as a senior at Wellesley in 1966, she was unaware of Harvard Business School until a prospective employer suggested he might hire her if she had an MBA. Second, she said that she was assigned to Section C, because Section D and G professors refused to teach women! Also at our table was Sam Ewing, one of the few Blacks in Steve’s class. The next morning, we met Richard America, Class of ’63, in the breakfast tent. A Professor Emeritus at Georgetown University School of Business, he told us about his work with developing business schools in Africa. We felt we had met a true agent of change.

Just today, my friend Robert Ames identified yet another agent of change, MJ Hegar:

Leave a Reply