The Everglades

Marjorie Stoneman Douglas lived a long, productive life. In her thirties and forties she wrote short stories for The Saturday Evening Post. In her fifties, she wrote The Everglades: River of Grass, which 70 years later is still the definitive book on the Everglades. In her sixties, she produced three novels and two nonfiction works. In her seventies, she directed the University of Miami Press. In her eighties she founded the Friends of the Everglades and led the fight to restore the vast river of grass so altered by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. In her nineties Douglas continued the fight to save the Biscayne Aquifer, which supplies Florida’s southeastern coast. In 1988 Ms. Magazine acclaimed her 60-year fight to save the Everglades as a “testament to the tenacious energy older women offer today’s world.” Amen! Douglas died in 1998 at the age of 108. Now her statue sits on a bench at Fairchild Tropical Botanical Garden, accepting homage from my granddaughters and me. I am now studying The Everglades: River of Grass and stand in awe of the depth of her knowledge and her vivid style.

Growing up in Texas, I was thoroughly immersed in Texas history. Living in Virginia for 45 years exposed me to that state’s rich traditions. As a relative newcomer to Florida, I have much to learn. Douglas is the perfect guide, inspiring me to think about what makes this state different. The principal difference is the Everglades, which originally comprised a large part of the state. It is a World Heritage site, unlike any place in the world. This ecological system extends over one hundred miles from above Lake Okeechobee to the Gulf of Mexico, with a width of fifty to seventy miles. Water moves down that almost invisible slope slowly, but inexorably–1.5 million acres of wetland. Fresh water from Lake Okeechobee has worn the oölitic limestone underneath into a broad longitudinally grooved valley. South of Biscayne Bay the ridges stretch to make the long spiny curves of the Florida Keys. On the east coast the rock is gouged deeply by an enormous oceanic river of warm water, two hundred fathoms (1,200 feet) deep , moving four to five miles an hour, the Gulf Stream.

Rising over the Glades is a tropical jungle of trees: mangroves, gumbo limbos, cypress, Sabal palms (the State Tree) and hundreds more. In the river of grass are alligators, American crocodiles, turtles, snails, otters and a wealth of fish. Glorious birds, such as sandpipers, sanderlings, ducks, ibis, pelicans, herons, egrets, and roseate spoonbills, nest here. Many of them inhabit the Wakodahatchee Wetlands, just ten minutes from our house, a reclaimed area that was once part of the Glades.

The people of the Everglades are an important part of the story. For hundreds of years the Calusa, Mayaimi, and Tekesta Indians were cut off from other American tribes and developed their own unique civilization. They made their own pottery, fashioned axes from conch shells, and set sharks’ teeth into wooden handles for effective knives. Their cypress canoes enabled them to make their way through the hammocks and live in harmony with their surroundings, that is, until the Spanish arrived.

Like Texas, Florida has a strong Spanish heritage. Shortly after Easter Sunday 1513, Juan Ponce de Leon landed on the Florida coast, noting “Pascua Florida: Flowery Easter.” The name stuck. More Spanish adventurers followed, “motivated by greed, glory, gold, and God.” Traffic in Indian slaves became a lucrative business. By 1520 the “deadly glittering tide” of Spanish conquest surged into Central and South America. The dominant cities became Veracruz on the Mexican coast and Cartagena on the South American mainland. The best way to get riches from these cities back to Spain, was to sail the Gulf Stream flowing between Cuba and the Florida coast; too many ships had wrecked along the Bahama passage, north of Hispaniola. As piracy increased, caravels were replaced with galleons and sailed in convoys. Newcomers failed to reckon with hurricanes, but the Indians of the coasts delighted in harvesting treasures from wrecked ships.

Douglas provides vivid details about Pedro Menendez de Avilés, the first Governor of Florida,1565 – 74, whom I described in my post on St. Augustine. Menendez established forts at St. Lucia above Canaveral, Tocobago at Tampa, San Antonio in Calusa Bay, and Tekesta on Biscayne Bay, but after his death they were abandoned. The power of Spain in the Caribbean, as in Europe, was rotting at the core. The white men departed, leaving the Indians ravaged by yellow fever, smallpox, and measles. Fewer people up and down the coast meant fewer wars. “Piracy as an organized affair was slowly broken up by tacit consent of the English, French and Dutch governments, now that they also owned property in the New World.” In 1763 Florida became English; Spain was only too glad to get Cuba in return.

Douglas lavishes attention on the Indians who survived Spanish contact and thrived in the centuries of peace that followed. The Muskogee-speakers, who would be the nucleus of the later “Seminoles,” came into Florida from the northeast. While I had always assumed that the Underground Railroad headed only north, those escaping slavery in Georgia, Carolina, and Alabama were much closer to Florida. The tribes of Florida accepted and made alliance with these runaways, whom Douglas describes in ways I had never appreciated:

These were the tall fierce black men of the most warlike tribes of the West African coast, taken only in war by the great slave-trading nation of the Dahomeys, their enemies, and sold to slavers supplying the West Indies and the continental colonies. The most intractable among them were the Ashantis of the Gold Coast, whom the French and Spanish learned not to buy, preferring the more docile slaves of the Niger. There were other fighting men–the rangy round-faced Senegalese from Dakar, the Ebos, and the Egbas. These were the men, who in Jamaica and the British West Indies, were the first to revolt. They began that endless series of uprisings and escapes which put the fear of the black man into the white man’s heart and gave the lie forever to the white theory that the Negro was happier in chains….They shared that innate love of liberty which was not exclusive to the colonial white man.

The Negro had a great deal to add to the Indian way of life, especially his age-long preoccupation with agriculture, which made him a harder everyday worker, on his own land, than the migratory hunting Indians. The Negro’s never sufficiently recognized legal shrewdness, which in Africa had produced his system of tribal courts, were to serve well the councils of his Indian allies, masters and relatives. He fought more fiercely even than the Indian. He had more to lose.

After only 21 years under England, Florida was returned to Spain in 1784 after the American Revolution. In 1808 the importation of Negro slaves into the United States was forbidden. The value of escaped Negroes and of Indians with Negro blood, rose enormously. At the insistence of the slave states, Florida was purchased from Spain in 1818. Andrew Jackson, the first territorial governor of Florida, saw the Indian as the frontiersmen’s bitter enemy. His view was that every Indian in Florida should be removed to the West and all Negroes, who had been free among them, and their free-born children, must be returned to slavery.

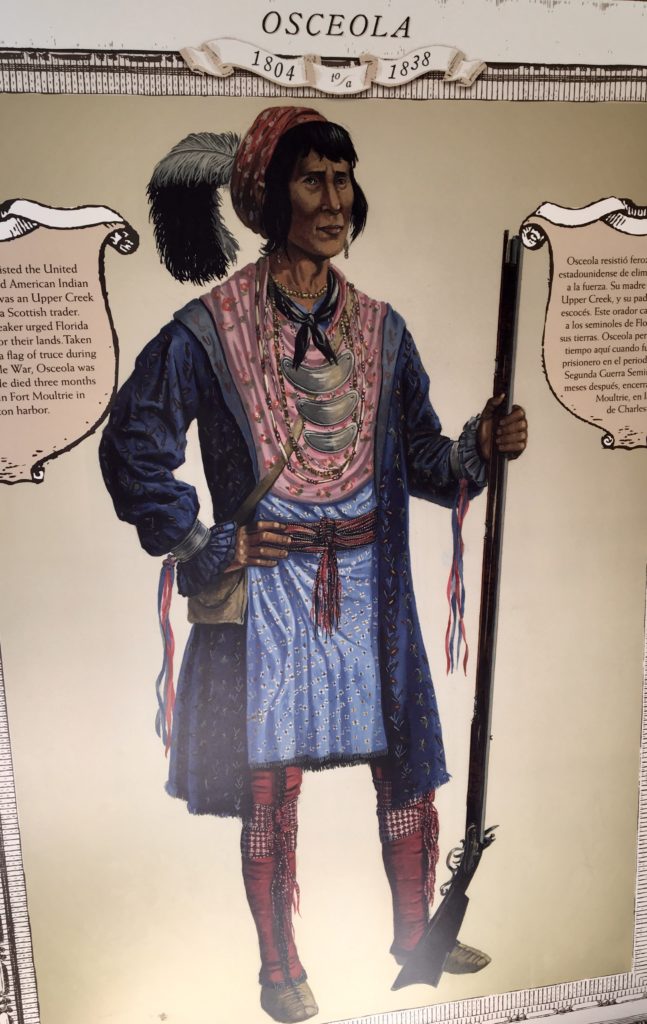

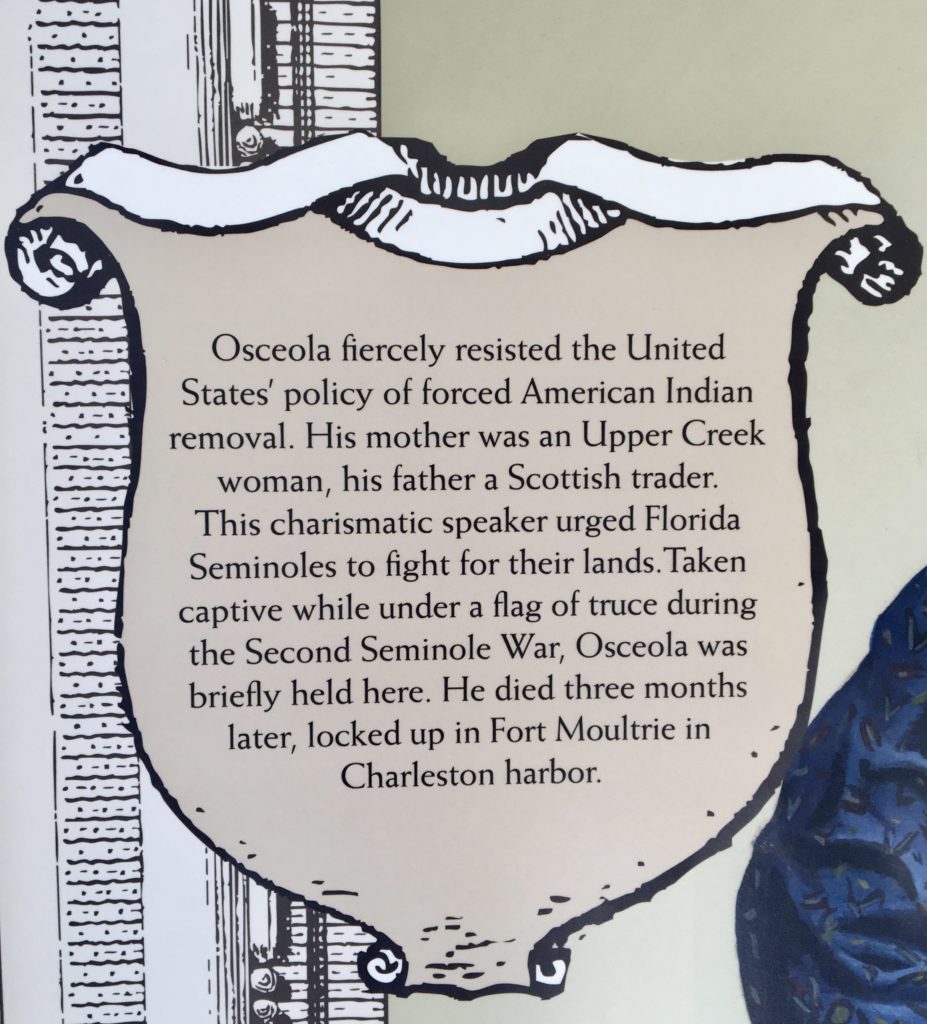

Among the Indian leaders who negotiated with the American government, I was particularly impressed with Osceola, whose portrait I had seen at the Fort in St. Augustine.

At a council meeting in April 1835, U.S. General Wiley Thompson told the Indians that if they refused to emigrate, they would be driven out by force.

Eight chiefs, likely promised beforehand good prices for their cattle and slaves, came forward to make their marks on the treaty. Others, called by name, only shook their head and sat or stood like stone. Osceola, when his name was called, walked forward deliberately. As the eyes of his elders followed him, fixed in shock, he said clearly, facing the table, ‘This land is ours, we want no agent.’ He moved his arm in one lightning gesture. The Americans stared at his knife quivering a little, stabbed into the table, through the long white paper. “That is the way I sign,” Osceola said and pulled his knife out and turned his straight brown back on the red face of General Thompson.

The Second Seminole War continued from 1835 – 42. For two years, 1838 – 40, General Zachary Taylor, whose name graced my children’s elementary school, commanded the army. He concentrated on keeping the Seminoles out of northern Florida, so that settlers could return to their homes, but ordered that no white men would be allowed to come into the war zone to claim as slaves the Negro prisoners of war. The Seminoles drifted south and concentrated on growing their crops and gathering supplies for the winter. The long, expensive war in Florida wore itself out. In 1842 Colonel William J. Worth recommended and received authorization to leave the remaining Seminoles on an informal reservation in southwestern Florida. Fort Worth TX and Lake Worth FL are named in his honor.

With the Indians out of the way, white settlers began to imagine what they could do with Florida’s lands. The U.S. Congress passed the Swamp Lands Act in 1850. At once, the Florida legislature secured the swamp lands from the Federal government and created the Board of Internal Improvement. Five hundred thousand acres of swamp and overflowed lands, in general known as the Everglades, thus came under the control of the state. Draining the land proved to be much more difficult than anyone imagined.

Writing in the New York Times under the headline “How to Drain a Swamp,” Malia Wollan succinctly summarizes what Douglas takes many pages to explain:

In 1847, the federal government commissioned a man named Buckingham Smith to survey the millions of acres of wetlands, which he described in a subsequent report as “worse than worthless.” By the early 20th century, the state began building what would eventually become 1,800 miles of canals, dams and levees that now reroute 1.7 billion gallons of water daily, only to discover unintended consequences. Once dry, Florida’s peat soils ignited in smoldering muck fires. In many places, the ground sank. The water table dropped. Saltwater invaded. Soils oxidized. Aquatic species disappeared.

That’s the state of affairs that Douglas described in the last chapter of her book, titled “The Eleventh Hour.” The Everglades National Park was established in December 1947, but the conflict between restoring the Glades and accommodating seven million Florida residents has continued for the last seventy years. Last year I saw an excellent exhibit on the Tamiami Trail at the Coral Gables Museum that detailed how that highway, nicknamed “Alligator Alley,” had dealt a major blow to the ecology of the Everglades and suggested ways to counteract its effects. Join me in supporting the work of the Everglades Foundation and others interested in restoring natural habitats and clean water.

Leave a Reply