Finding Repose

Wallace Stegner’s novel, Angle of Repose, is a powerful portrait of pioneers in the Western United States in the years 1876-90, during which transcontinental railroads were completed and natural resources began to be tapped. The central character is a strong, independent woman who misses her friends in the East, but rises to the challenges she encounters in the West. Reading how Susan Burling Ward made each new situation work for her and her family made me consider the many creative ways one can seek and find repose.

Wallace Stegner’s novel, Angle of Repose, is a powerful portrait of pioneers in the Western United States in the years 1876-90, during which transcontinental railroads were completed and natural resources began to be tapped. The central character is a strong, independent woman who misses her friends in the East, but rises to the challenges she encounters in the West. Reading how Susan Burling Ward made each new situation work for her and her family made me consider the many creative ways one can seek and find repose.

Her adventures in California, Colorado, and Idaho brought to mind my own travels in those states. Her brief time in Michoacan, Mexico, reminded me of my friend Lilburn, who thrived for several years in 1940s Mexico. This beautifully written book has earned a place on my “all-time favorites shelf” with A Gentleman in Moscow and All the Light We Cannot See–three great stories, set in far-away places, featuring memorable individuals trying to make wise choices every day. Each book shows models of finding repose.

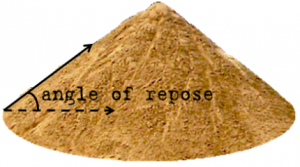

The title metaphor is particularly apt, given that Susan Ward’s husband, Oliver, is a mining engineer who depends on such principles: “When bulk granular materials, such as mine tailings, are poured onto a horizontal surface, a conical pile will form. The internal angle between the surface of the pile and the horizontal surface is known as the angle of repose and is related to the density, surface area and shapes of the particles.”

The title metaphor is particularly apt, given that Susan Ward’s husband, Oliver, is a mining engineer who depends on such principles: “When bulk granular materials, such as mine tailings, are poured onto a horizontal surface, a conical pile will form. The internal angle between the surface of the pile and the horizontal surface is known as the angle of repose and is related to the density, surface area and shapes of the particles.”

Oliver, who confronts nitty-gritty problems every day, is a man of few words. Susan is an artist to whom words mean the world. Early on, Susan goes down into a mine with Oliver, but finds it difficult to grasp his motivation and his unique skills. He, in turn, lacks understanding of her craft. Each word she writes and each subject she sketches are carefully chosen. Susan sends insightful, illustrated articles to journals in New York City that place high value on news of the West. The money she earns helps the family survive financial hardships. Both Susan and Oliver think deeply and work hard, but often they seem to be climbing opposing mountains at impossibly steep angles. Yet their marriage endures for over sixty years, tragic cracks and all. The novel details how the characters keep adjusting the density and shape of each aspect of their lives, striving to achieve repose.

Stegner (1909 – 93), shown here with his wife Mary, was an Eagle Scout and an environmentalist. He is known as the founder of Stanford University’s creative writing program and the Dean of Western writers. Their 60-year marriage was a “personal literary partnership of singular facility,” wrote Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. in The Geography of Hope, A Tribute to Wallace Stegner, “a partnership in which he did the writing and she enforced the writerly environs. He brought her breakfast in bed; she fed him new interests and fended off distractions.”

Stegner (1909 – 93), shown here with his wife Mary, was an Eagle Scout and an environmentalist. He is known as the founder of Stanford University’s creative writing program and the Dean of Western writers. Their 60-year marriage was a “personal literary partnership of singular facility,” wrote Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. in The Geography of Hope, A Tribute to Wallace Stegner, “a partnership in which he did the writing and she enforced the writerly environs. He brought her breakfast in bed; she fed him new interests and fended off distractions.”

The character Susan Burling Ward is based on Mary Hallock Foote, whom Stegner first came across when he joined the Stanford faculty in 1946. In a thoughtful introduction to the edition of the book I read, Jackson J. Benson writes that Stegner discovered that Foote “was good and hadn’t been noticed.” He put one of her stories on the reading list for his American literature class. One of his students was intrigued and found out that Foote had a granddaughter living not far away. The Foote family gave the student Mary Hallock Foote’s papers, including many letters, to use as a basis for his doctoral dissertation, but he never finished writing it. Stegner took the papers with him on vacation in the mid-1960s and after much mulling, decided to link fictionalized versions of her letters with a contemporary narrator to create a multi-generational story. That way, the narrator, grandson of Susan and Oliver Ward, can compare his own wrecked marriage with that of his grandparents and contrast his Victorian grandmother with his hippie assistant from Cal-Berkeley.

The character Oliver Ward is based on Mary Hallock Foote’s husband, engineer Arthur DeWint Foote. It was Foote who conceived the ambitious irrigation project in Idaho that proved to be the ultimate challenge in the novel. But it was Wallace Stegner whose imagination transformed Mary Hallock Foote’s letters into Susan Ward’s correspondence and turned these Wikipedia entries into the living, breathing, multi-dimensional characters I found so compelling.

As Steve and I approach our 55th wedding anniversary this coming June, I found much wisdom in Angle of Repose. I knew I could trust Stegner, because he, too, was married almost 60 years. As I observed Susan Ward adapting herself to each venue her husband chose, I thought of how Steve’s strong focus on golf has led us to live in Florida and spend vacations in Scotland. Any challenges I have faced have been much, much more benign than hers. Still, I found it interesting to view my own adaptations through an outside lens. Like Susan Ward, I have turned to reading and writing, and also playing piano in an effort to make the most of my remaining years. The multi-generational narrative forced me to consider the challenges my own parents and grandparents faced. How I wish that I had more of their papers in order to understand them better. That lack renewed my intention to turn this blog into a memoir that could be passed on to my own grandchildren.

As the novel shifted from the Wards’ first location, Grass Valley in northeastern California, to New Almaden and Santa Cruz in the Bay Area, I thought of a trip I took with my daughter Shelby in 1992 to visit my dear friend Alyce McDermott Boster and her family in Los Altos. I still remember picking a lush orange from a tree in their yard, and deeming it a symbol of California fecundity. Los Altos is just thirty minutes north of New Almaden, where the novel depicts Oliver Ward mining mercury. Hopefully, I’ll someday return to visit the Almaden Quicksilver County Park and see the mine and the mountains Stegner described.

Here’s a picture of Alyce the day we both graduated from Rice in 1966. Steve and I both credit Alyce for seeing that we were meant for each other, before we saw it ourselves. Alyce and Dave were kind to host Lilli and her friends in Sydney, Australia in 1987. They came to our 50th anniversary celebration in 2016, not long before they passed that mark, too. After worldwide adventures with Dave, Alyce became the office director of the English department at Stanford, where Stegner taught. I think Stegner would have appreciated how Alyce kept that department running smoothly for many years.

Here’s a picture of Alyce the day we both graduated from Rice in 1966. Steve and I both credit Alyce for seeing that we were meant for each other, before we saw it ourselves. Alyce and Dave were kind to host Lilli and her friends in Sydney, Australia in 1987. They came to our 50th anniversary celebration in 2016, not long before they passed that mark, too. After worldwide adventures with Dave, Alyce became the office director of the English department at Stanford, where Stegner taught. I think Stegner would have appreciated how Alyce kept that department running smoothly for many years.

One of the crucial tests that the Wards encountered was in Leadville, Colorado. It was really difficult even to get there in 1877; making a profit was even harder. Leadville is yet another link to another couple who have been married for over 50 years, Claire and Bill Stitt, dear friends since 1968. They now divide their time between Fort Myers FL and Edwards CO. In 2014 Claire took us from Edwards, over well-paved roads, to Leadville, the highest city in the United States. There we visited an old mine and the Mining Museum. Here are some photos I took that connect us to Angle of Repose.

The dramatic peak of the novel took place in Idaho, where Oliver Ward was trying to re-direct the Snake River, no less, to irrigate the desert. That River recalled a very special trip. In 1985, our family flew from Austin Tx, where we had spent a wonderful week on Lake Travis with Steve’s sister Karen, to Denver, where we met my mother (who had flown in from Amarillo), and flew together to Salt Lake City–three state capitals in one day! There we rented a car and drove to Jackson Hole, Wyoming. A visit to the Grand Tetons was the closest place I could share with my family my love of the Rocky Mountains. Grand Tetons National Park is much more accessible than Glacier National Park, where I worked as a maid at Many Glacier Hotel in 1964.

How proud we all were of 7-year-old Shelby when we completed a hike on Jenny Lake Trail, only five years after the multiple surgeries she had to correct hip dysplasia. I kept a panorama photo of the Tetons over my desk for the next thirty years, trying to stay focused on lofty ideals. After my mother (then age 82) flew back to Amarillo, we took a raft trip on the Snake River. Hurray for Rocky Mountain exuberance! Lilli is right in front; Shelby and I are in the middle; and David and Steve (white hat and sleeve) are in the rear of the photo. Four years later, those of us 12 and above rafted through the Grand Canyon–another story!

Leave a Reply