Height of Wisdom

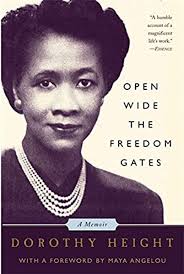

Dr. Dorothy Height was a woman who knew how to get things done. The headquarters building of the National Council of Negro Women at 633 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington DC bears her name and honors the strength of her organizational talents. She led this Council and associated institutions to become powerful forces for change. I remember seeing her name frequently in the Washington Post when we lived in the DC area, but failed to appreciate how very much she accomplished. Every US President from Franklin Roosevelt to Bill Clinton sought and relied on her counsel. Reading her 2003 memoir, Open Wide the Freedom Gates, enlightened me about the vision and wisdom needed to lead others to work together effectively. I wish I had had such a guide to follow in the organizations I led.

Dr. Dorothy Height was a woman who knew how to get things done. The headquarters building of the National Council of Negro Women at 633 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington DC bears her name and honors the strength of her organizational talents. She led this Council and associated institutions to become powerful forces for change. I remember seeing her name frequently in the Washington Post when we lived in the DC area, but failed to appreciate how very much she accomplished. Every US President from Franklin Roosevelt to Bill Clinton sought and relied on her counsel. Reading her 2003 memoir, Open Wide the Freedom Gates, enlightened me about the vision and wisdom needed to lead others to work together effectively. I wish I had had such a guide to follow in the organizations I led.

Born on March 24, 1912 in Richmond VA, she soon moved with her family to Rankin PA, part of the Great Migration of southern Negroes to the North. An avid student, by age 16 she became the Pennsylvania State Champion of Impromptu Speech. The subject assigned to her only ten minutes in advance was the Kellogg-Briand Peace Pact, a 1928 treaty among sixty nations, which called for the renunciation of war as an instrument of national policy. Stepping out onto the stage in Harrisburg, she saw two thousand people in the audience but only one other person of color–a janitor, standing in the back by an exit door. He smiled at her. Her account of that event reveals not only her values, but her lifelong ability for turning setbacks into opportunities.

I said that I believed that peace would come in the hearts of all people someday, but it would take time. I recalled that two thousand years before, the message of peace had been brought to the world, but there was not room at the inn for the messenger, who was turned away at his birth. His parents were turned away at the inn, just as my principal and teacher had been turned away that afternoon at the Harrisburg Hotel because I was with them and I was a Negro. “But the people at the hotel who turned us away did not know anything about me,” I said. “They did not want me simply because my skin was colored.”

I proposed that if we could follow Briand’s idea, accepting the message that came to us two thousand years ago, we would learn to respect one another. We would try to live with one another and work together. Only as we began to see each other as human beings, I concluded, as part of the same human family, would we find lasting peace.

A unanimous judgment by a panel of all-white judges awarded her first prize. She must have felt the elation I felt when I was elected Railroad Commissioner at Texas Girls State in 1961. While my challenges, smarts and achievement pale in comparison with hers, I well remember the confidence that a state-level win conveys to a teenager.

Two years after her winning impromptu speech, Dorothy went on to win a four-year college scholarship from the IPBO Elks by compressing the 20-minute speech she had prepared into the 10- minute maximum allowed. She applied to Barnard College in New York City and was accepted, but at the required interview, she found that two other Negro students had already filled Barnard’s quota of two per year. New York University, by contrast, gave her a warm welcome.

I, too, had a free ride to college. Rice University was tuition-free then and I had a four-year scholarship from the Phillips Petroleum Company that almost covered room and board. Dorothy worked harder for her scholarship and had several jobs while attending NYU. At the Unemployment Council, an advocacy group for the jobless in the Williamsburg section of Brooklyn, she learned to deal with conflict without intensifying it.

Saying things like, “We don’t have a policy on that question,” or, “There’s nothing we can do to help you,” is inflammatory. If you listened to people, then figured out what the welfare system, limited though it was, could do to help, you could get a little respect from them even though they were hungry, frustrated, and angry because “the system” seemed so hopelessly inadequate….I would not denounce the system as long as I believed that it offered channels through which you could work for change.

Height earned a bachelor’s in education and master’s in psychology at NYU. Her first job was as a social worker in Harlem. Soon she joined the staff of the Harlem Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA). Before long she was working with the National YWCA to integrate all YWCA facilities. Here is a succinct account of Height’s life by Arlisha Norwood of the National Women’s History Museum:

During a chance encounter with African American leader Mary McLeod Bethune, Height was inspired to begin working with the National Council of Negro Women (NCNW). Through the NCNW, Height focused on ending the lynching of African Americans and restructuring the criminal justice system. In 1957, she became the fourth president of the NCNW. Under her leadership, the NCNW supported voter registration in the South. The NCNW also financially aided several civil rights activists throughout the country. Height was president of NCNW for 40 years.

In 1963, Height, along with other civil rights activists organized the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Although she played a role in the march, she was not invited to speak. In fact, originally no women were included on the program at all. Height and Anna Arnold Hedgeman persuaded the other organizers to allow a woman to speak. Despite the apparent gender discrimination in the Civil Rights Movement, Height continued working on the front lines.

In addition to her work in the United States, Height traveled extensively. She served as a visiting professor at the University of Delhi, India and with the Black Women’s Federation of South Africa. For all her efforts during the Civil Rights Movement, Height was awarded and recognized by many organizations. In 1989, she received the Citizens Medal Award from President Ronald Reagan and in 2004, Height was honored with the Congressional Gold Medal. The same year, Height was inducted into the Democracy Hall of Fame International. She also received an estimated 24 honorary degrees. On April 20th, 2010, Height passed away at the age of 98. Her funeral was held at Washington National Cathedral.

In Chapter Sixteen of the book, “A Place in the Sisterhood,” Height describes her work in Delta Sigma Theta Sorority. “My years of involvement have afforded me wisdom I would never otherwise possess and given me an even greater thirst for knowledge and for new ventures to be of service to others. The power of sisterhood for African American women is a very strong force indeed.” Vice-President Kamala Harris agrees. She joined Delta Sigma Theta at Howard University, where it was founded in 1913.

Rice had no national sororities, but I felt sisterhood in the Elizabeth Baldwin Literary Society and my residential college at Rice; in the Junior League of Northern Virginia 1984-90; in Northern Virginia Music Teachers Association 1979 – 2013; and in women’s circles at Cherrydale United Methodist Church in Arlington VA, 1977-2015, and currently, at First Presbyterian Church, Delray Beach FL. Now that I’ve learned how effective Dorothy Height was, I am pondering how much better I could have done in the leadership roles I had. This book conveys the vision and skills that dynamic leaders need. That’s why I’m recommending it to aspiring younger leaders.

The annual gala of the National Council of Negro Women is called “Uncommon Height.” Dorothy Height happened to be tall and she definitely had uncommon intelligence. I think of her as the “Height of Wisdom.” Here, in Height’s own words, are three examples of her wisdom that I want to remember.

p. 114 Many have assumed that the pattern of segregation exists because of prejudice. Quite the contrary, it seems to me that people are prejudiced because they have been estranged by segregation. They don’t know one another, and they fear the unknown. Tasks and meaningful activities undertaken together help people find each other around common goals. Lesson: get acquainted with a wide range of people.

p. 197 Under Height’s leadership, NCNW initiated a pilot project in Gulfport MS that enabled low-income families to take possession of homes as buyer-occupants. Included in the project were day-care and recreation centers. Critically, she obtained the support of the Office of Economic Opportunity, the Mississippi Home Builders Association, and the Ford Foundation. Soon the project expanded to several other cities. In the end, 18,761 units were constructed at an estimated value of $407 million. When HUD Secretary George Romney toured the area after Hurricane Camille in 1969, the only site intact was Forest Heights in Gulfport. It was saved because Ike Thomas, a resident, risked his life to close the floodgate. Asked why he did so, he answered: “for the first time in our lives, we had something of our own.”

p. 246 The United Nations Decade for Women, 1975-85, was a watershed for women’s empowerment. In three landmark conferences the United Nations brought together more than twenty thousand women representing every occupation and every point of view imaginable. I was involved in each of the conferences…..We tried individual to individual to establish rapport and common bonds around issues of peace and justice and women’s dual burden of working inside and outside the home. Many of the African women knew the YWCA, and many were eager to start organizations like NCNW in their own countries.

Leave a Reply