Whistling Vivaldi

Claude Steele‘s book, Whistling Vivaldi: How Stereotypes Affect Us and What We Can Do was sent me by the Rice Annual Fund when I was raising money for our class’s 50th Reunion Gift. It was the Common Reading book for incoming students in 2015. I finally got to it last week and found it timely in light of the recent demonstrations of white supremacy and Black Lives Matter. In 2014 I wrote about stereotypes that affect Dallas, but Steele’s more incisive and very lucid explanations of how stereotypes keep people from achieving their full potential made me think more deeply about the subject.

The title comes from the experience of Brent Staples, a psychology graduate student at the University of Chicago, a young African American male dressed in informal clothing, walking down the streets of Chicago’s Hyde Park neighborhood. Steele quotes him:

I became an expert in the language of fear. Couples locked arms or reached for each other’s hand when they saw me. Some crossed to the other side of the street. People who were carrying on conversations went mute and stared straight ahead, as though avoiding my eyes would save them…

I’d been a fool. I’d been walking the streets grinning good evening at people who were frightened to death of me. I tried to be innocuous, but didn’t know how…I began to avoid people. I turned out of my way into side streets to spare them the sense that they were being stalked…Out of nervousness I began to whistle and discovered I was good at it. My whistle was pure and sweet–and also in tune. On the street at night I whistled popular tunes from the Beatles and Vivaldi’s Four Seasons. The tension drained from people’s bodies when they heard me. A few even smiled as they passed me in the dark.

Steele notes that Staples was dealing with a bad stereotype about his race that was in the air on the streets of Hyde Park–the stereotype that young African American males in this neighborhood are violence prone. Then Steele describes how his research over many decades deals with overcoming other stereotypes, such as that women are poor in math, or white athletes lack athletic prowess.

As a piano teacher I was constantly aware of how my students imposed stereotypes on themselves (“I get nervous playing in public,” “I’m not as good as Diana”) as they prepared to perform in recitals, festivals and competitions. I learned to make sure they had the chance to try out their pieces in small groups before going on to larger events, but now I see that I could have done more to alleviate the fears of those who felt threatened because they thought they weren’t as good as more accomplished pianists. In graduate school, I learned to manage my own performance anxiety. I could have used the wisdom contained in this book to help my students manage theirs. Then, even the least secure students could have played Mozart as confidently as young Staples whistled Vivaldi.

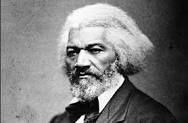

Before reading this book, I had just finished Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave. I had skimmed it years ago when Judith and I visited the Frederick Douglass National Historic Site in Washington DC. It was our President’s ignorance of who Douglass was that made me read it again. I found a refresher course in how horribly slaves were treated and why, indeed, it’s important to assert today that Black Lives Matter! Douglass’ narrative underscores the historic sources of negative stereotypes about African Americans, even as it shows how cleverly he was able to overcome them; Whistling Vivaldi explains the damage they still do.

Before reading this book, I had just finished Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave. I had skimmed it years ago when Judith and I visited the Frederick Douglass National Historic Site in Washington DC. It was our President’s ignorance of who Douglass was that made me read it again. I found a refresher course in how horribly slaves were treated and why, indeed, it’s important to assert today that Black Lives Matter! Douglass’ narrative underscores the historic sources of negative stereotypes about African Americans, even as it shows how cleverly he was able to overcome them; Whistling Vivaldi explains the damage they still do.

Steele concludes that stereotype threat is a general phenomenon:

Negative stereotypes about our identities hover in the air around us. We avoid situations where we have to contend with this pressure. It’s not all-determining, but it persistently, often beneath our awareness, organizes our actions and choices, our lives–like whether we choose to sit next to a black person on a train, or how well we do on a round of golf or an IQ test.

What a pleasure it is to see that Rice has taken the lessons of this book to heart. Instead of threatening incoming students with failure, as we were in 1962, the University has designed a program to recognize stereotype threats for what they are and bolster the self-confidence of incoming students, especially those who are the first in their family to attend college. Look at all the assistance available. So proud of my alma mater!

Leave a Reply