The Wisdom of Frederick Douglass

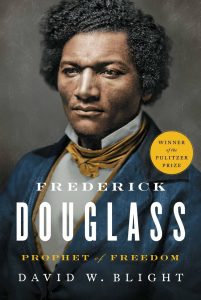

Can a 19th-century prophet help us through the crisis we now face? Several years ago I read Frederick Douglass’ Autobiography after visiting Cedar Hill, his last home in DC. Last December, at a Frederick Douglass art exhibit in Savannah, I bought this Pulitzer Prize-winning biography of Douglass. I read half, then put it aside. Finally, in this 12th week of Corona hunkering, I resolved to finish it. The murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis, followed by countrywide protests, made me wonder whether Douglass’ example might provide ways to bridge the continuing divide between black/white economic and criminal justice. What has our society learned in the 122 years since Douglass died? How can I be true to my own Credo, “to do justice, love kindness and walk humbly…”?

Can a 19th-century prophet help us through the crisis we now face? Several years ago I read Frederick Douglass’ Autobiography after visiting Cedar Hill, his last home in DC. Last December, at a Frederick Douglass art exhibit in Savannah, I bought this Pulitzer Prize-winning biography of Douglass. I read half, then put it aside. Finally, in this 12th week of Corona hunkering, I resolved to finish it. The murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis, followed by countrywide protests, made me wonder whether Douglass’ example might provide ways to bridge the continuing divide between black/white economic and criminal justice. What has our society learned in the 122 years since Douglass died? How can I be true to my own Credo, “to do justice, love kindness and walk humbly…”?

David W. Blight, Professor of American History and Director of the Center of the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition at Yale University chose a special moment to begin his magnificent biography: the unveiling of the Emancipation Memorial on April 14, 1876, the 11th anniversary of President Lincoln’s death. This first memorial to Lincoln, funded by appreciative former slaves and black Civil War veterans, is in Lincoln Park, eleven blocks east of the Capitol building. In all my years in Washington I never visited this Park, never saw this statue; Northeast DC was too risky at first, then I got too busy. The Lincoln Memorial on the Mall was dedicated 46 years later.

More than 25,000 people attended the 1876 ceremony. Frederick Douglass delivered the keynote address before President Ulysses S. Grant, his cabinet, Chief Justice Morrison Waite, Senators and Congressmen. The statue features President Lincoln holding the Emancipation Proclamation before a kneeling African American man, who was modeled after Archer Alexander, the last person captured under the Fugitive Slave Act. The man’s arms are extended to show that his shackles have been broken. For many people, including Frederick Douglass, the monument perpetuated stereotypes about African Americans. But Douglass, from his own visceral experience as a slave who plotted his own escape, fully understood how freedom for black Americans was both seized and given. Blight notes that no African American speaker had ever before faced all the leadership of the federal government in one place; and no such speaker would ever again until Barack Obama was inaugurated president in 2009. Blight narrates how Douglass began with a history lesson.

Referring to the “vast and wonderful change in our condition,” Douglass observed that no such open commemoration by blacks in Washington would have been tolerated before the Civil War’s transformations, without opening “flood-gates of wrath and violence.” Douglass congratulated all on this “contrast between then and now…..the “long and dark history” of slavery is a matter of the past, replaced now by “liberty, progress, and enlightenment.”

Then Douglass switched to appraising Lincoln. “Lincoln was preeminently the white man’s president,” he intoned in his forceful baritone, “entirely devoted to the welfare of the white man. He was ready and willing at any time during the first years of his administration to deny, postpone, and sacrifice the rights of the colored people to promote the welfare of the white people of the country…..During the secession crisis and into 1862, Lincoln was willing to pursue, recapture, and send back the fugitive slave to his master.”

Blacks, despite grief and bewilderment at the president’s slow actions, concluded “that the hour and the man of our redemption had somehow met in the person of Abraham Lincoln. Under his rule, slaves were lifted from bondage to liberty; black men exchanged rags for Union soldiers’ uniforms; two hundred thousand marched in the cause; the domestic slave trade was abolished, and the Confederate States, based upon the idea that our race must be slaves, was battered to pieces. Under his rule the Emancipation Proclamation emerged, making slavery forever impossible in the United States.”

“My white fellow-citizens…you are the children of Abraham Lincoln. We are at best only his stepchildren by adoption. Despise not the humble offering we this day unveil,” he pleaded, “for while Abraham Lincoln saved for you a country, he delivered us from a bondage, one hour of which was worse than ages of the oppression your fathers rose in rebellion to oppose.”

The further I read in the biography, the more I admired Douglass and wondered why I hadn’t learned more about him in my history classes. On page 592, Blight comments that Douglass “never stopped searching to unravel the mystery behind his highly visible life: how a barefoot slave boy on the Wye plantation in Maryland ever made it to lecture halls in London and Edinburgh, or how a wretched teenager in rags in the Talbot Country courthouse jail ever made it to the White House to discuss emancipation with Lincoln. Douglass could never entirely believe his own myth even as he forged it..”

In October 1864 in Syracuse NY, Douglass addressed a black convention of 150 representatives after Sherman had defeated Atlanta and looked far into the future. “Nations could learn righteousness from supreme crises, he argued, and this was a moment when mourning mingles everywhere with the national shout of victory. Douglass asserted that the opportunity to crush slavery, throw back racism, and reinvent the American republic around principles of racial equality “may not come again in a century.”

Douglass was only 45 when Emancipation was achieved. He lived another thirty-two years. What did he do with the rest of his life? His son’s scrapbooks and other materials collected by a black doctor in Savannah, that Steve and I saw at the SCAD Art Museum, are rich sources. David Blight describes how they inspired him in this half-hour interview:

Douglass’s Insights for Our Time

In 1864 Douglass celebrated the re-election of Abraham Lincoln with a speech at the Bethel AME Church in Fell’s Point, Baltimore. He ended by calling white and blacks to exercise a new psychological logic, to look into their hearts and minds to cross the racial divide of centuries. As we watch demonstrators protest, are we looking into each other’s hearts and minds? Do we realize how much privilege the light color of our skin imparts? Can we imagine the everyday fears blacks have?

Palm Beach Post, 5 June 2020: Donald Fennoy, Palm Beach County’s first black schools superintendent, delivered an emotional speech Wednesday about the death of George Floyd and its impact on his family. He’s the chief executive of the nation’s tenth-largest school district, supervisor of more than 22,000 employees and commander of a police force hundreds strong. But Donald Fennoy, Palm Beach County’s first black schools superintendent, is also scared. Scared for himself, he said, and scared for his 11-year-old son.

Lilli sent me a link to this video of Frederick Douglass’ descendents delivering a scorching speech, which illuminates the basic flaw in our history and provides updated viewpoints:

To overcome second-class citizenship, Douglass urged blacks to save money, buy land, educate their children, and forge a new generation “capable of thinking as well as digging.” He promised them that the “more intelligent and refined they became, the more white people will respect you.” He was talking about blacks building home equity for financial security. Can we revamp federal programs to make that more possible?

In 1944, the G.I. Bill guaranteed loans for veterans. The terms made monthly mortgage payments cheaper than rent in public housing. In the years right after World War II, veterans’ mortgages made up more than 40 percent of all home loans. Between 1944 to 1971, the Veterans Administration spent $95 billion on benefits.But the VA used FHA standards in dispensing loans. As a result, it excluded many black veterans. Also, the states were given free rein to administer the program. Most of the VA boards were all-white. As a result, black veterans in the South were denied access.

In his book, “When Affirmative Action Was White,” Ira Katznelson described the consequences, “By 1984, when G.I. Bill mortgages had mainly matured, the median white household had a net worth of $39,135. The comparable figure for black households was only $3,397, or just 9 percent of white holdings. Most of this difference was accounted for by the absence of homeownership.”

In addition to wealth disparities, Blacks often feel unsafe where they live. In the summer of 1874 in Vicksburg, Mississippi 300 blacks were killed. In Mississippi’s 1875 statewide election campaigns, white vigilante mobs attacked and shot people with impunity in broad daylight. Have this situation improved? Fast forward 140 years, here are statistics from today’s news.

Police killed at least 104 unarmed black people in 2015, at the rate of two per week.

Nearly 1 in 3 black people killed by police in 2015 were identified as unarmed, though the actual number is likely higher due to underreporting

36% of unarmed people killed by police were black in 2015 despite black people being only 13% of the U.S. population

In the 1960s, the Civil Rights Movement achieved many new opportunities for blacks. Now that another half century has passed, how can we come together to create the multiracial society Douglass dreamed of? My son-in-law Sean sent me this inspiring poem by Leslie Dwight:

What if 2020 isn’t cancelled?

What if 2020 is the year we’ve been waiting for?

A year so uncomfortable, so painful, so scary, so raw that it finally forces us to grow.

A year that screams so loud, finally awakening us from our ignorant slumber.

A year we finally accept the need for change.

Declare change. Work for change. Become the change.

A year we finally band together, instead of pushing each other further apart.

2020 isn’t cancelled, but rather the most important year of them all.

My friend Kristine Johnson is an Episcopal minister in California. She writes a blog called “The Rooted Rector.” Today her post was about a messy beach.

Sometimes when I get to the beach it is pristine – just sand and waves. Not today. Today it is strewn with kelp, grasses, a couple of dead seagulls, plastic bottle caps, candy wrappers, and who knows what else. And if you look out in the water, you will see more stuff being washed ashore.

Life feels kind of like the beach today. The crises are piling up, things that have been floating along are crashing ashore, making a tangled mess. The pandemic, racism and its ugly consequences, politics and religion, climate change, gun violence…

Feeling overwhelmed? This beach is too big and too littered for one person to clean up alone….. Our reaction may simply be to go back inside our houses – those of us who are privileged enough to be able to do that.

Please don’t. Because the mess won’t go away by itself. The people whose lives are caught in those tangled tendrils – people whose lives are every bit as important and sacred as ours – cannot, and must not be expected to, fix it themselves. It will take all of us to clear this beach, to make it clean enough so all may enjoy it.

Okay, Kristine. My first step is to send your beach-cleaning message to my readers as I present Frederick Douglass’ devotion to winning freedom. I confess the great privilege I have due to the color of my skin. I realize how disadvantaged I was not to have classes with blacks until graduate school. Though I have met many black musicians and taught a few, I regret that I have yet to form a lasting relationship with someone whose skin is black.

My best bet, I believe, is to continue my work with organizations that reflect Douglass’ ideals: MusicLink Foundation, Family Promise, Literacy Coalition of Palm Beach County, League of Women Voters, and the First Presbyterian Church of Delray Beach. When schools reopen I will continue to tutor in Title I schools and raise money so that Safety Patrols from Crosspointe can visit Washington DC. I will encourage my grandchildren to become aware of both privileges and duties.

Leave a Reply