Profound Lecture

At Chautauqua on July 4 Risa Goluboff, Dean of the Law School at the University of Virginia, delivered a truly outstanding lecture, After Charlottesville: The Process Of Living And Rebuilding After The White Supremacist Rallies In August 2017. Current newscasts emphasize its value. I’m still pondering her words. It was the best of five lectures highlighting Chautauqua’s Week Two theme, Uncommon Ground: Communities Working Toward Solutions.

At Chautauqua on July 4 Risa Goluboff, Dean of the Law School at the University of Virginia, delivered a truly outstanding lecture, After Charlottesville: The Process Of Living And Rebuilding After The White Supremacist Rallies In August 2017. Current newscasts emphasize its value. I’m still pondering her words. It was the best of five lectures highlighting Chautauqua’s Week Two theme, Uncommon Ground: Communities Working Toward Solutions.

After James Alex Fields Jr. killed Heather Heyer and injured dozens more two years ago, Goluboff said the community faced the question: What to do in the face of evil? She asked that question as a Jew, as a mother, a Constitutional law scholar, a civil rights historian, the dean of a law school, a university leader and a resident of Charlottesville. I sat near the front and took copious notes, but Jamie Landers’ report in The Chautauquan Daily the next day, which I quote liberally here, was more detailed. It’s long, but worth close attention. I have added headings and printed in bold or red what impressed me most.

The first task is to mourn–the loss of life, the injuries, and the loss of innocence and security. Mourning increased with the Tree of Life synagogue shooting in Pittsburgh in October 2018 and the Poway synagogue shooting in San Diego in April 2019.

After mourning, celebrate. “You celebrate the bravery and humanity of the people on that day,” she said. “You celebrate the bravery of Susan Bro, Heather Heyer’s inimitable mother who carries on her legacy. You celebrate all the signs that showed up, almost instantly, in every store window in Charlottesville and on every lawn in Albemarle county, declaring that we choose love over hate and that those people are not us.”

Third, take stock. “You ask, ‘How did we do? How did our institutions do? Did we respond as we needed to all the people in our community who felt themselves vulnerable and in need?’ ” The people in the most immediate need were Jews and African Americans, but they were not the only vulnerable groups in the white supremacists’ narrow view of who belongs in American society.

“Their narrow view does not include Jews or Muslims or anyone of a religious faith other than Christian,” she said. “It does not include LGBTQ Americans or those with disabilities, those who are anything but white, those who were not born in the United States, and for the most part, it doesn’t include women. It is a muscular, violent, misogynistic, white, heterosexual, cisgender norm that denigrates and dehumanizes everyone that doesn’t fit into that very narrow category.”

Fourth: Take Action. Once the Charlottesville community took stock, it took action.At the University of Virginia School of Law, Goluboff led a committee focused on recovering from and responding to the violence. She said their actions addressed four charges.

- Ensure the immediate safety and security of everyone in the community. We wrote a report about how our institution did that day and we took steps to increase immediate safety and security concerns; we changed policies and we added personnel.

- Recommit to the university’s values. We recommitted) to values that were the opposite of the hate, the intolerance and the violence that were on display on Aug. 11 and 12,” she said. “Values of diversity, humanity, equality, tolerance and belonging. Those are our values as a university, and this was a moment where we said we must recommit to them. That will not be our future as these people would have it be.

- Figure out how to utilize the university’s significant intellectual resources. “How do we change our institution?” she said. “How do we self-examine and self-reflect and have the hard conversations to move forward?” In terms of community efforts, Goluboff believes Charlottesville is reflecting the progress of the university, but is still a deeply stratified and unequal place. In the aftermath of Aug. 11 and 12, the fissures, the division and a lot of anger came to the fore. “It wasn’t always pretty and it hasn’t always been easy. Sometimes civility has gone by the wayside. Civility can seem like a privilege when you are talking about life and death, and not everyone has a platform on which to speak.

- Restore civility, Charlottesville has introduced multiple resources, such as a civilian police review board, unity and diversity days and a clergy collective. “We have many people committing to a future of this place that is more just, more equal and more tolerant than it was in the past,” she said. Although the community is still in the midst of recovery, Goluboff said she is proud of the progress. “We are reckoning with our future, we are reckoning with our present and we are reckoning with our past,” she said.

The fifth part of facing evil: take the long view. The long view is divided into two sets of “intertwined issues,” speech and equality. [Frankly, I’m only beginning to understand some of the distinctions Goluboff made, but studying them closely has helped.]

The Long View, Part One: SPEECH

Goluboff explained that when the white supremacists came to Charlottesville, they came disguised as peaceful protestors. When violence ensued, a lot of questions arose: “Why were the white nationalists allowed to come? Why were they allowed to speak? At what point did their peaceful protest turn into unlawful violence? Was it always unlawful, or did that happen after they began?”

For at least the last 100 years, America has possessed a judicially enforceable First Amendment that protects peaceful, nonviolent free speech. At the same time, the content of speech has remained unlimited. The government cannot pick and choose what speech to protect and what speech not to protect, and that means that if the neo-Nazis and white supremacists had come and not been violent, their speech would have been protected.

The inclusion of all speech raises one question: When thinking about a country founded on “dialogue through differences,” how does one count speech that they find not only disagreeable, but “abhorrent and dehumanizing”? That question is a product of generational tension. “We see our young people asking, ‘Why is hate speech protected?’ ” she said. “It’s not enough to answer them to say, ‘It is.’ We have to grapple with the challenges they’re offering to the Constitutional regime that many of my generation think is the right Constitutional regime.”

According to Goluboff, part of the problem is that America is stuck in a “false dichotomy” between claims of freedom of speech and freedom from harm. The false dichotomy is based on a caricature that free speech in modern-day America is mostly exercised by radical conservatives and white supremacists. “That is not the case,” she said. “We would do well to remember that when free speech became Constitutionally protected, it did so as a result mostly of those on the left: communists, anarchists, civil rights protestors, labor union organizers, Vietnam War protestors and religious dissidents.”

On the other side of the false dichotomy, the caricature is of young people who “don’t want to hear anything they disagree with. There is a distrust of their tactics of shutting down speakers, of demanding trigger warnings,” Goluboff said. “There is a distrust of their goals for the content of Constitutional law, that it should think about the content of speech and that hate speech should not be protected.”

Goluboff said that caricature is overdrawn, as shown in the controversy over football players kneeling during the national anthem. Whatever you think substantively about that controversy, you might think about the fact that it is also a claim not to have to be confronted with expression that makes one uncomfortable, that makes the viewers say, ‘I don’t want to have to see how you feel about our flag,’ ” she said.

Another example is how people curate their news intake based on personal beliefs.“We can choose to read and listen to news that agrees with our own perspective,”she said. “How far is the distance between saying ‘I only want to hear this’ from ‘I don’t want to hear that’; from ‘You shouldn’t say that’; from ‘I have a right for you not to be allowed to say that.’ That is not a very far distance.”

Goluboff has three preconditions to overcome that false dichotomy. The first is to recognize the harmfulness of speech. “We say ‘sticks and stones may break your bones, but speech can never harm me,’ ” she said. “That’s not true. Speech harms. To say that speech harms doesn’t mean that it harms in a Constitutionally cognizable way. It’s not to say that if speech harms, then the speech of the white supremacists shouldn’t be protected. That’s not what I’m saying. Just because the speech is Constitutionally protected, doesn’t mean it’s not harmful.” In addition, one must think about how speech harms different people in different ways. Although the attack affected Goluboff, she recognizes that it did not affect her humanity in the way it did for others.

The second precondition is to recognize that those differential impacts are systematic. “They are not idiosyncratic, they are not individualized,” she said. “They are systematic and they have everything to do with equality and inequality. It is very difficult to have truly free speech when you don’t have a truly equal society.”

The third precondition is understanding when people speak, they are speaking within communities and social norms.“We exercise our Constitutional rights alongside so many other values all the time that I think we forget when we just want to say ‘Well, I have a right,’ ” she said. “Yes, you have a right. How do you want to exercise that right? In relation to whom? With what kind of language? In what community?”

The Long View, Part Two: EQUALITY

The second issue included in the long view is equality. Goluboff said many people were not surprised by the protests because Americans tell false stories of the country’s history. Those stories make them forget what racism and inequality look like, making them forget that those problems still exist.

“The story we like to tell about ourselves, which is partial and incomplete as all stories are, is that once upon a time there was slavery, but that ended,” she said. “Then there was segregation, but that ended, too, because of Brown v. Board of Education and the Civil Rights Movement. Then we had an African American president and we entered into a post-racial era and now, we are all equal. We are all on a level playing field.”

The assumption that racism is dead is where a lot of resentment comes from, Goluboff said. “We are not done,” she said. “Racism and slavery reach into every facet of American life. For 300 years of slavery and 100 years of segregation? Really? In a generation or two it’s all going to be uprooted? It’s not.”

How should the Constitution create equality? Goluboff said it needs the help of two paradigms. The first one is the anti-discrimination paradigm, which states the government should never separate people on the basis of race.“The way to have equality is for the government to never think about race, and if you live in an unequal society, then the government not thinking about race will lead to equality,” she said.

The alternative paradigm is the anti-subordination paradigm, which states that if the government remains neutral, it is allowing inequality to continue. “In order for us to get to a place of more equality, the government might in fact be required to take steps to end subordination and to end inequality,” Goluboff said.

Goluboff revisited a moment from a few days after the Charlottesville violence. She was attending a panel at the law school where someone referred to white supremacists as “an unpopular minority.” Two reactions followed.

At first, Goluboff said she felt gratified. “In the 1950s and the 1940s and the 1960s, the periods I studied, the white supremacists were the dominant majority and the civil rights activists were the uncommon minority,” she said. “I was gratified to think that flipped and that days after, a unanimous, bipartisan Congress condemned what happened in Charlottesville.”

At the same time, Goluboff felt afraid. “As a historian taking the long view, I know how unpopular minorities become dominant majorities and it doesn’t always go in one direction and it doesn’t always go in the direction you want it to,” she said. “It’s up to us if we want to make sure that these events were a last gasp of that white supremacy rather than a new upsurge and a new era.”

Because the City of Charlottesville has done so much to avoid a new era of white supremacy, Goluboff wants people to avoid speaking of Charlottesville as a lament. The hometown she loves, that has been through so much, deserves to ring out as a rallying cry.

Take all of the resources you have, all of the education you have, all of the institutions of which you are a part, and put them to work to recommit to the values of love, tolerance, understanding and justice in the face of hate, intolerance and violence.

After answering several questions from the audience of some 4,000 people, Goluboff smiled at the last question: “Would you consider accepting a position on the US Supreme Court?” That question seemed to be on everyone’s mind; we all rose in a standing ovation.

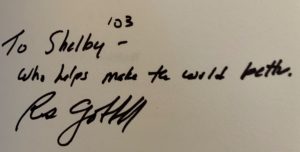

An hour later, with Goluboff’s book in hand, I asked her to autograph The Lost Promise of Civil Rights for my daughter Shelby, who graduated from UVA Law School in 2003. After inquiring about and listening to some of Shelby’s recent activities, she inscribed the book in a way I treasure.

Addendum posted July 26, 2019: I found an interesting article that I have saved since 2013 by Manny Fernandez in the New York Times that details how Dallas has changed since its reputation was devastated by the assassination of John F. Kennedy, November 22, 1963. I expect that Charlottesville may be frequently reexamined, too.

Addendum posted November 18, 2021: Indeed re-examination of the 2017 demonstration in Charlottesville continues. Here’s a headline from this story in today’s New York Times:

Four Years After ‘Unite the Right,’ Charlottesville Still Struggles to Move On

Many residents hoped the town would become an example of racial reconciliation. It hasn’t happened.

Leave a Reply