Women’s Equality

Top on my list of places to see in a short visit to Northern Virginia was the Belmont-Paul Women’s Equality National Monument in Washington DC. Designated only last year by President Obama, this is a place I had wanted to see since Nina Pitkin and I visited the tiny Women’s Suffrage Museum at the old DC jail in Lorton VA. On June 21 Mary Walter and I were immediately impressed by the beauty of the mansion at 144 Constitution Avenue NE, next to the Hart Senate Office Building. Built in 1800 by Robert Sewall of Maryland, it was destroyed by the British in the invasion of Washington in August 1814.

Top on my list of places to see in a short visit to Northern Virginia was the Belmont-Paul Women’s Equality National Monument in Washington DC. Designated only last year by President Obama, this is a place I had wanted to see since Nina Pitkin and I visited the tiny Women’s Suffrage Museum at the old DC jail in Lorton VA. On June 21 Mary Walter and I were immediately impressed by the beauty of the mansion at 144 Constitution Avenue NE, next to the Hart Senate Office Building. Built in 1800 by Robert Sewall of Maryland, it was destroyed by the British in the invasion of Washington in August 1814. Sewall rebuilt it in 1820 and his descendants lived there for almost a century. In 1922, Senator and Mrs. Porter Dale of Vermont purchased and rehabilitated the house. The Dales sold the house to the National Woman’s Party (NWP) to use as their headquarters in 1929. The NWP renamed the property the “Alva Belmont House” in honor of Alva Belmont, NWP President from 1920-1933. Belmont (born in Alabama and married to William Kissam Vanderbilt from 1875 to 1896) donated thousands of dollars to the women’s equality movement and gave the NWP the ability to purchase the new headquarters. Alice Paul had founded the NWP in 1916 to address women’s suffrage and equality. Under Paul’s leadership, the NWP refocused the women’s suffrage movement from a state-by-state effort to a push for a constitutional amendment.

Sewall rebuilt it in 1820 and his descendants lived there for almost a century. In 1922, Senator and Mrs. Porter Dale of Vermont purchased and rehabilitated the house. The Dales sold the house to the National Woman’s Party (NWP) to use as their headquarters in 1929. The NWP renamed the property the “Alva Belmont House” in honor of Alva Belmont, NWP President from 1920-1933. Belmont (born in Alabama and married to William Kissam Vanderbilt from 1875 to 1896) donated thousands of dollars to the women’s equality movement and gave the NWP the ability to purchase the new headquarters. Alice Paul had founded the NWP in 1916 to address women’s suffrage and equality. Under Paul’s leadership, the NWP refocused the women’s suffrage movement from a state-by-state effort to a push for a constitutional amendment.

Mary and I could only imagine how Alice Paul was able to lead the effort to get the 19th Amendment passed and ratified, before the National Women’s Party even had this building for their offices. The Monument website describes their tactics:

Nonviolent, dramatic protests were the hallmark of the NWP’s operations in Washington. Suffrage marches, daily picketing and arrests at the White House, and speaking tours raised the public profile of the movement. Protesters faced daily violence from both passers-by and the police, including having their banners ripped from their hands and being physically attacked and arrested. While imprisoned (at Lorton) for their activism, some women protested through highly-publicized hunger strikes that resulted in forced feedings and even worse prison conditions. The brutality with which the women were treated created enormous public support for suffrage.

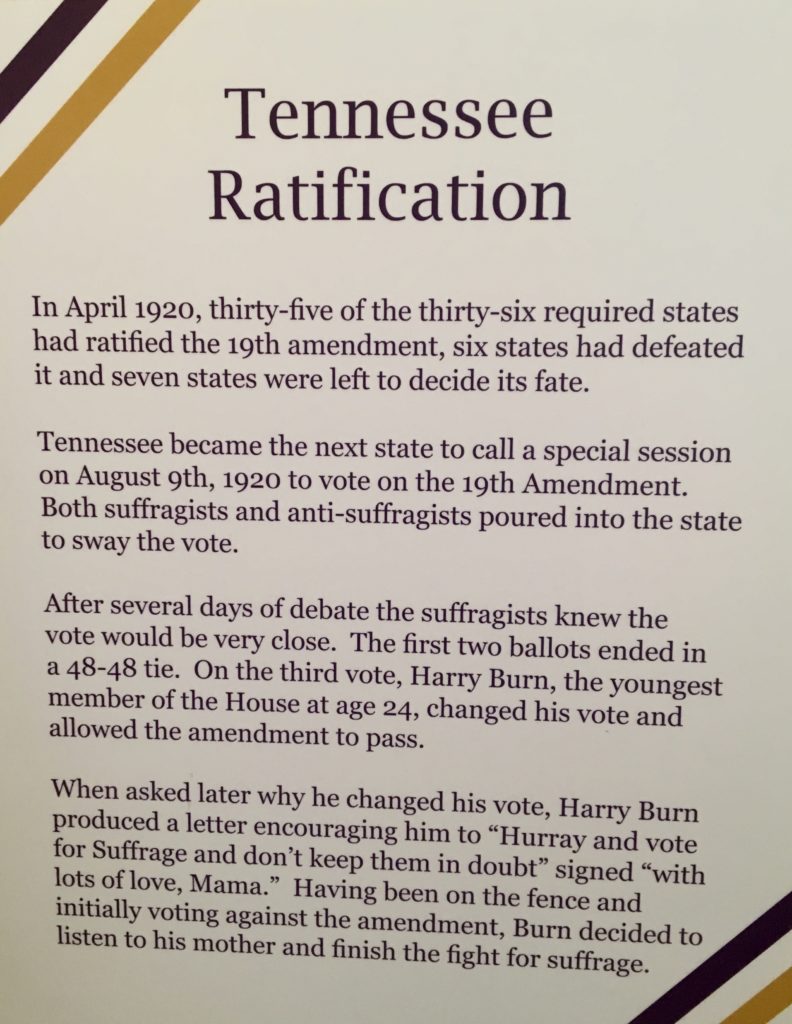

The House of Representatives passed the 19th Amendment in May 1919 by 304 votes to 89. Two weeks later, on June 4, 1919, the Senate passed the 19th Amendment by two votes over its two-thirds required majority, 56-25. In just fourteen months, the National Women’s Party and the Women’s Suffrage Association successfully lobbied governors and state legislators for ratification. By August 26, 1920 (now celebrated as Women’s Equality Day) 36 of the 48 existing states (a three-fourths majority) had ratified the amendment in time for women to vote in the 1920 election. My mother, born in 1903, was not eligible to vote until 1924. I feel sure she paid her poll tax and voted then. She made sure I paid my poll tax in 1965, when I turned 21.

Glad to see that Texas did its duty, but notice that most of the South refused to ratify the 19th Amendment, though they have since corrected that error. Mary and I especially appreciated young Harry Burn in Tennessee, who listened to his mother.

It was a joy to see a woman Park Ranger on the premises. Catherine Cilfone, a native of San Antonio who also speaks Spanish, engaged us and other visitors in conversation about the history of women’s rights. One visitor inspired us to check out the Rally for Planned Parenthood on the lawn of the Capitol nearby. It was a beautiful day for watching democracy in action after contemplating how far we women have come.

Leave a Reply