Richard Serra, Sculptor

This 67-foot-tall structure made from COR-TEN steel stands outside The Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth. It‘s name is “Vortex”, sculpted by California-born artist Richard Serra and acquired by The Modern in 2002. Its grandiose stature and sweeping, rust-colored design make Vortex fascinating. When Shelby’s family lived in Dallas and our friends Susan and Jerry Pittman lived in Grapevine, I found myself drawn to The Modern, where Susan was a docent. I wanted to step inside Vortex and look up to see the sky above through the seven-sided opening at the top of the sculpture. If you clapped your hands or said a word, you could hear the sounds reverberate against the metal. My friend Linda, who lived in Ft. Worth, said “Vortex was a family favorite – my grandkids called it the scream tower.”

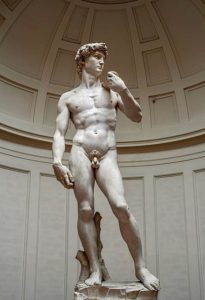

This 67-foot-tall structure made from COR-TEN steel stands outside The Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth. It‘s name is “Vortex”, sculpted by California-born artist Richard Serra and acquired by The Modern in 2002. Its grandiose stature and sweeping, rust-colored design make Vortex fascinating. When Shelby’s family lived in Dallas and our friends Susan and Jerry Pittman lived in Grapevine, I found myself drawn to The Modern, where Susan was a docent. I wanted to step inside Vortex and look up to see the sky above through the seven-sided opening at the top of the sculpture. If you clapped your hands or said a word, you could hear the sounds reverberate against the metal. My friend Linda, who lived in Ft. Worth, said “Vortex was a family favorite – my grandkids called it the scream tower.” When the East Building of the National Gallery opened in 1978, Washington at last had a showcase for more modern art. On frequent visits, I began to notice sculptures by David Smith and other sculptors. But did they hold a candle to Michelangelo? I remember when Lilli and I visited Florence in 1998, I burst into tears when I encountered his David.

When the East Building of the National Gallery opened in 1978, Washington at last had a showcase for more modern art. On frequent visits, I began to notice sculptures by David Smith and other sculptors. But did they hold a candle to Michelangelo? I remember when Lilli and I visited Florence in 1998, I burst into tears when I encountered his David.

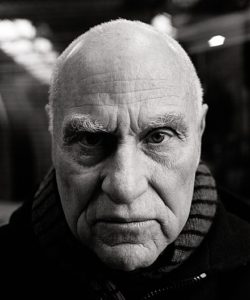

Richard Serra, who set out to become a painter but instead became one of his era’s greatest sculptors, inventing a monumental environment of immense tilting corridors, ellipses and spirals of steel that gave the medium both a new abstract grandeur and a new physical intimacy, died on Tuesday at his home in Orient, N.Y., on the North Fork of Long Island. He was 85.Mr. Serra’s most celebrated works had some of the scale of ancient temples or sacred sites and the inscrutability of landmarks like Stonehenge. But if these massive forms had a mystical effect, it came not from religious belief but from the distortions of space created by their leaning, curving or circling walls and the frankness of their materials.This was something new in sculpture; a flowing, circling geometry that had to be moved through and around to be fully experienced. Mr. Serra said his work required a lot of “walking and looking,” or “peripatetic perception.” It was, he said, “viewer centered”: Its meanings were to be arrived at by individual exploration and reflection.

In several places, I have read that Serra’s works expand one’s consciousness in unique ways and may leave you feeling anxious. The highly charged participatory nature of Serra’s works has led to controversy. A legal battle in New York City resulted in the forced removal of Serra’s “Tilted Arc” from the city’s Federal Plaza in 1989. People were afraid that the big steel piece might tilt over on them!

In his review of “Richard Serra Sculpture: 40 Years,” a 2007 exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Michael Himmelman wrote

The art is about the basic stuff of sculpture, isolated and recast: mass, weight, volume, material. What matters in the end are your own reactions while moving through the sculptures, at a given moment, the works being Rorschachs of indeterminate meaning.The other day in the museum’s garden, where two big Serras from the 1990s have been parked for some weeks, children dashed down the curved, leaning, fun-house corridors of “Intersection II,” while a trio of young women with their T-shirts rolled halfway up sunbathed (before a blushing guard appeared) on the ground inside “Torqued Ellipse IV,” its enclosing wall bent, curved and folding outward, conveniently forming a giant face tanner. All around, office workers sloughing off the afternoon and tourists resting tired feet roused themselves from scattered garden chairs to survey the two sculptures, sauntering through them like explorers happening upon a South Sea island, squinting up into the sky from time to time to fix their locations in space.

Actually they were explorers. These shapes and experiences are new. That’s about the best, and the rarest, compliment you can give to any artist.

Richard Serra graduated from the University of California-Berkeley with a BA in English Literature before switching to visual art. At Yale he studied with Josef Albers and earned an Masters in Fine Arts in 1964. While in Paris on a Yale fellowship for the next two years, he befriended composer Philip Glass and explored Constantin Brâncuși‘s studio, both of whom had a strong influence on his work. His time in Europe also catalyzed his subsequent shift from painting to sculpture. Back in New York, he came into contact with Donald Judd, whose sprawling works in concrete Lilli and I saw at the Chinati Foundationin Marfa, Texas in 2008.

Serra’s work is well known abroad. In Amsterdam in July 2022, it was joy to see Serra’s “Sight Point” outside the Stedelijk Museum and look up and out through it. Having seen Vortex in Fort Worth, I recognized it as his right away

In Washington, Serra’s sculpture “Five Plates, Two Poles” is in the lobby of the East Building of the National Gallery, where I had first encountered David Smith’s works. Here are two views of this work. I find it less inviting than “Vortex” or “My Curves Are Not Mad.” Does it command the attention Mercury does in the Rotunda of the Main Building? Maybe not, but we’re in a new age. Could “Five Plates and Two Poles” perhaps help us confront issues in our divided country?

Rest in Peace, Richard Serra. Thank you for stretching my mind and providing new experiences to help all of us understand the world we live in. And thank you Fort Worth Modern for showing what I consider his best work, “Vortex,” a sculpture I could really get into.

Leave a Reply