St. Augustine History

St. Augustine, older than Jamestown VA or Plymouth MA, is 250 miles north of Boynton Beach. Recently, our friends Nina and Roger invited us to inaugurate their newly renovated guest quarters in St. Augustine Beach. In 2015 we visited them when St. Augustine was celebrating its 450th anniversary and we had returned in 2021. Besides great golf for Steve, the rich history of this place has me entranced.

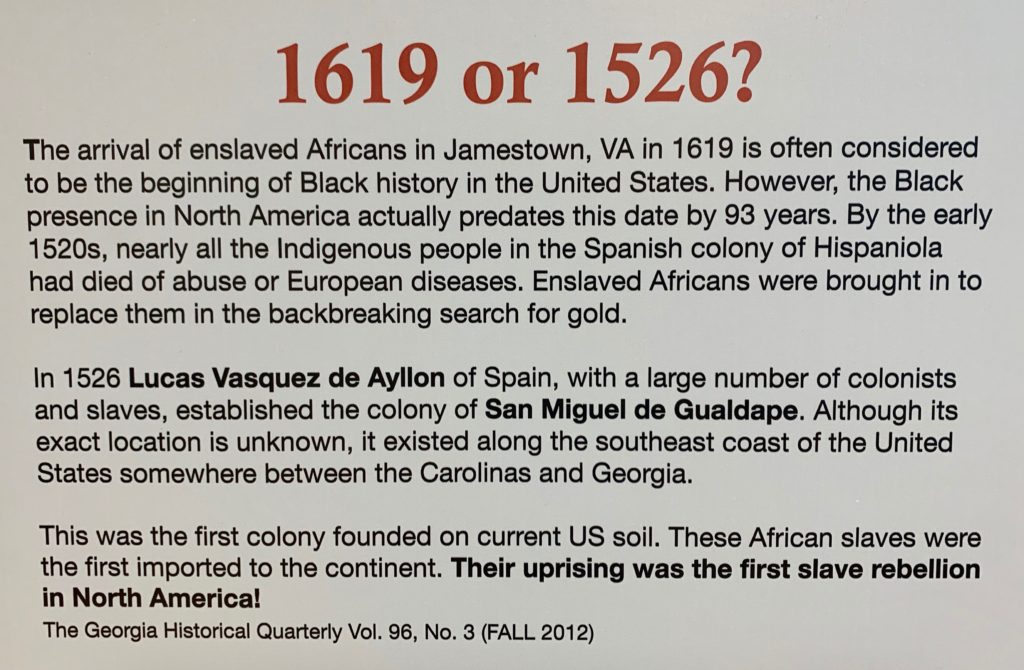

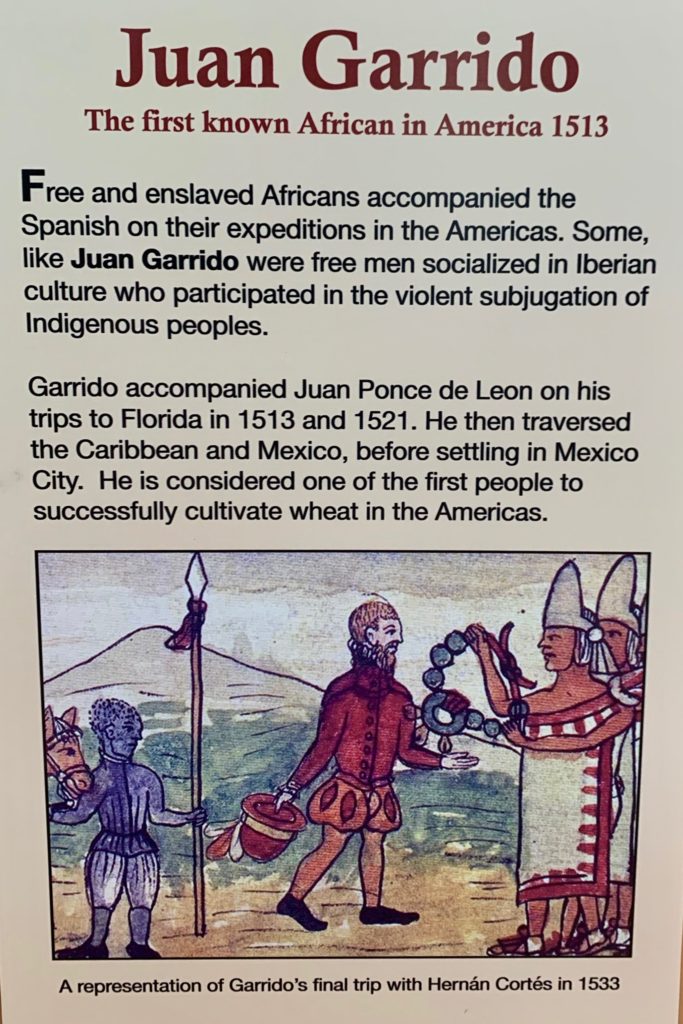

Juan Ponce de Leon was the first European to arrive in 1513. He was accompanied by an African free man named Juan Garrido. Half a century later, Spanish Admiral Pedro Menéndez de Avilés had the honor of naming the city. He arrived on September 8, 1565, eleven days after land was first sighted by his ships on August 28, the Feast of St. Augustine. The city served as the capital of Spanish Florida for over 200 years.

The 1763 Treaty of Paris, ceded Florida to Great Britain in exchange for the return of Havana and Manila. The vast majority of Spanish colonists in the region left Florida for Cub. Florida became Great Britain’s colony, but it lasted only twenty years. Because of the political sympathies of its British inhabitants, St. Augustine became a Loyalist haven during the American Revolutionary War. Great Britain returned Florida to Spain in 1783; Florida became a U.S. state in 1845.

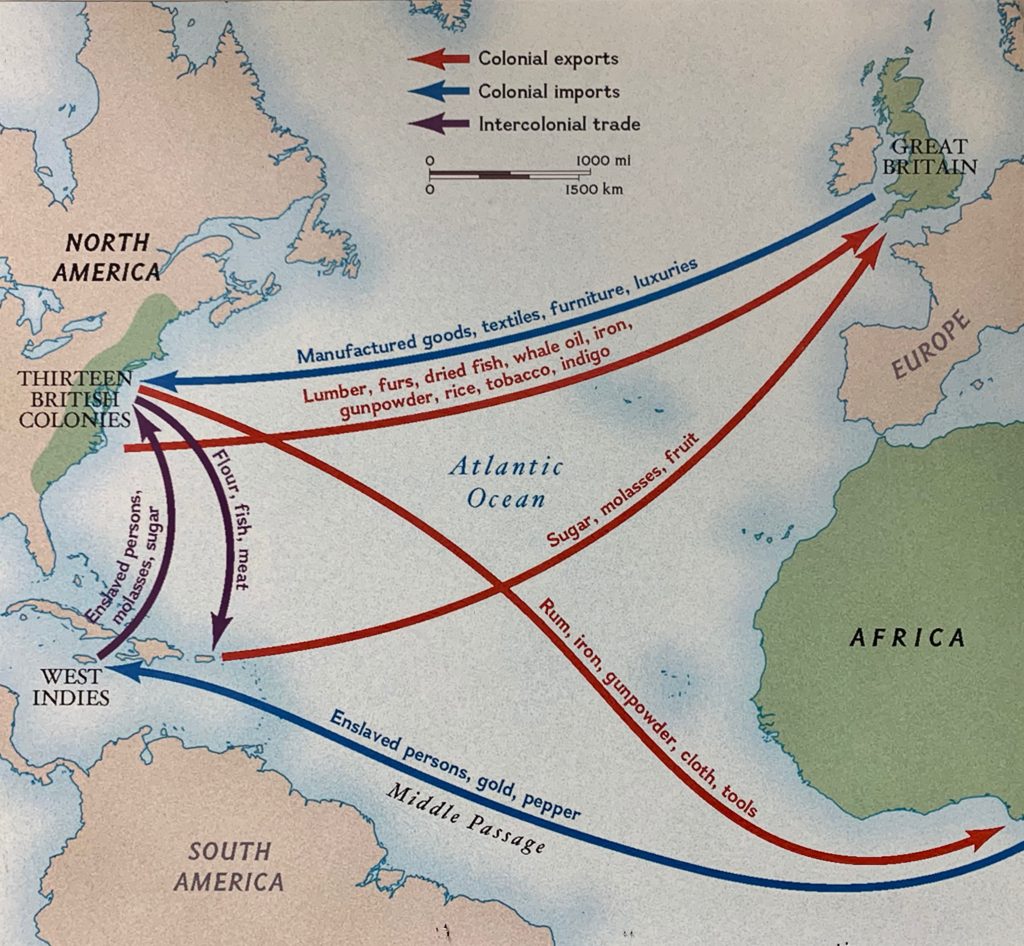

Nina and I had spent many hours in the historic district in previous visits. This time we explored the city’s history in Lincolnville to the South. Settled by newly-freed slaves after the Civil War, and named for President Lincoln, the Lincolnville Historic District played a pivotal role in the nation’s Civil Rights Movement. At the Lincolnville Museum and Cultural Center we gained fresh perspectives on the Triangular Trade of the Colonial period. Exhibits highlighted unique aspects of slavery in Spain and how they affected the treatment of slaves in Florida. For example, some slaves who escaped from Georgia had the chance to gain freedom by enlisting in the Spanish militia and converting to Catholicism.

- The origins of African slavery in the Americas are found in Moorish Iberia, today’s Spain and Portugal. After the Islamic invasion of Iberia in the 800s, the number of Africans in Europe increased dramatically. For the next 700 years the Islamic “Moors” occupied parts of Iberia. They were expelled from Portugal in 1250, but not until 1492 from Southern Spain. During that time, the Moors brought settlers and slaves of many nationalities and the people of Spain became familiar with Africans, both slave and non-slave.

- One of the most striking aspects of slavery in Iberia is that it was not primarily associated with skin color. After the Muslims were expelled from Portugal in 1250, the Portuguese began traveling to West Africa to trade and replenish their lost labor base. By the mid-1550s sub-Saharan Africans became the dominant slave population in Iberia, but in the minds of early modern Iberians, slavery was not directly linked to Blackness.

- Even though enslaved people in Iberian overseas colonies stood little chance of ever being ransomed, in legal terms slaves were viewed as captives or prisoners, rather than as personal property. Unlike the chattel system that developed in English American colonies, slavery in the early modern Iberian world was still considered a temporary condition, and enslaved people could obtain some protection or recourse from the Church and the Crown.

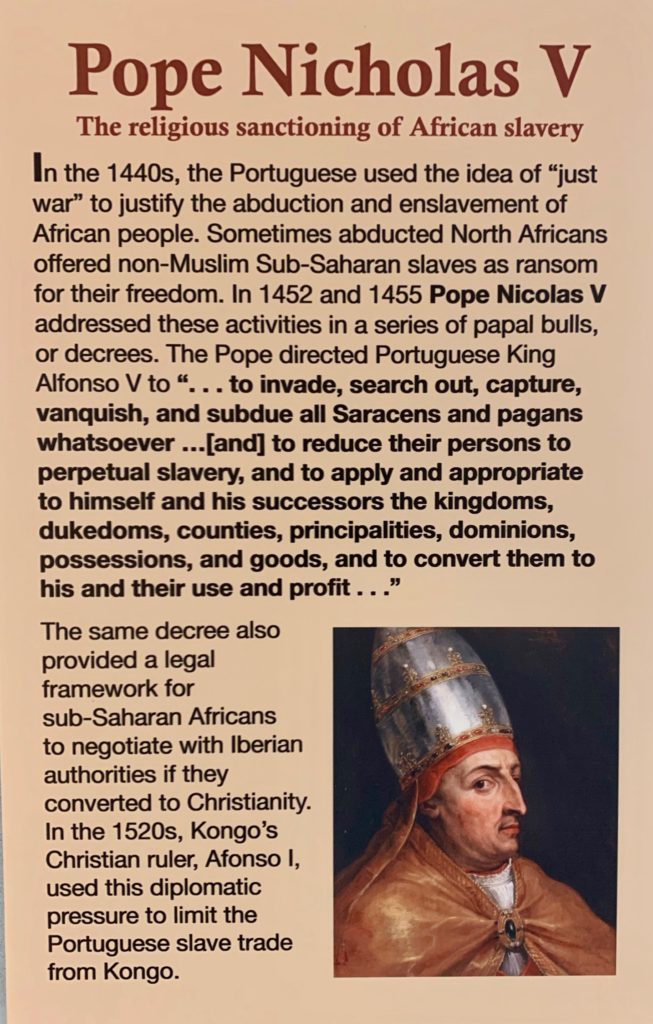

- Prince Henry the Navigator opened the African trade in about 1440 and found slaves to be one of the most lucrative commodities for trade with Europe, along with gold, ivory and spices. As you see below, Prince Henry had the blessing of the Pope. The Portuguese controlled the slave trade in the Americas during the early decades of settlement. By 1700, some 1-1/2 million African people had been brought to America unwillingly as slaves.

5. Africans were the only group in the Americas of the 1500s with resistance to the diseases of three continents. They survived the smallpox that struck the Indians of Mexico during the invasion by Hernán Cortés. The physical inability of both Europeans and American Natives to withstand the new disease climate of 16th century America was fateful for African Americans. By the 1550s black skin came to be associated with the ability to perform hard physical labor. Social attitudes quickly developed to institutionalize this idea, perhaps the most devastating legacy for Black Americans today.  6. In 1738, the governor of Spanish Florida, Manuel de Montiano, ordered a settlement be constructed two miles north of St. Augustine for the growing Free Black community established by fugitive slaves who had escaped into Florida from the Thirteen British Colonies. This new community, Fort Mose, would serve as a military outpost and buffer for St. Augustine, as the men accepted into Fort Mose had enlisted in the colonial militia and converted to Catholicism in exchange for their freedom. Here are my photos of Fort Mose.

6. In 1738, the governor of Spanish Florida, Manuel de Montiano, ordered a settlement be constructed two miles north of St. Augustine for the growing Free Black community established by fugitive slaves who had escaped into Florida from the Thirteen British Colonies. This new community, Fort Mose, would serve as a military outpost and buffer for St. Augustine, as the men accepted into Fort Mose had enlisted in the colonial militia and converted to Catholicism in exchange for their freedom. Here are my photos of Fort Mose.

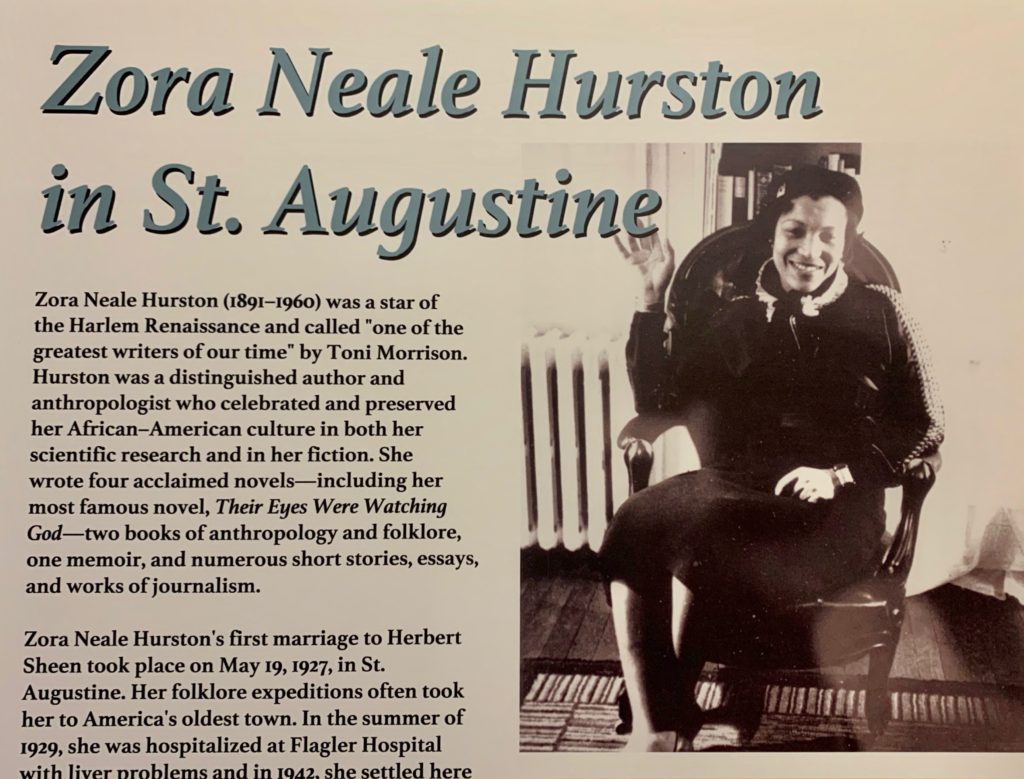

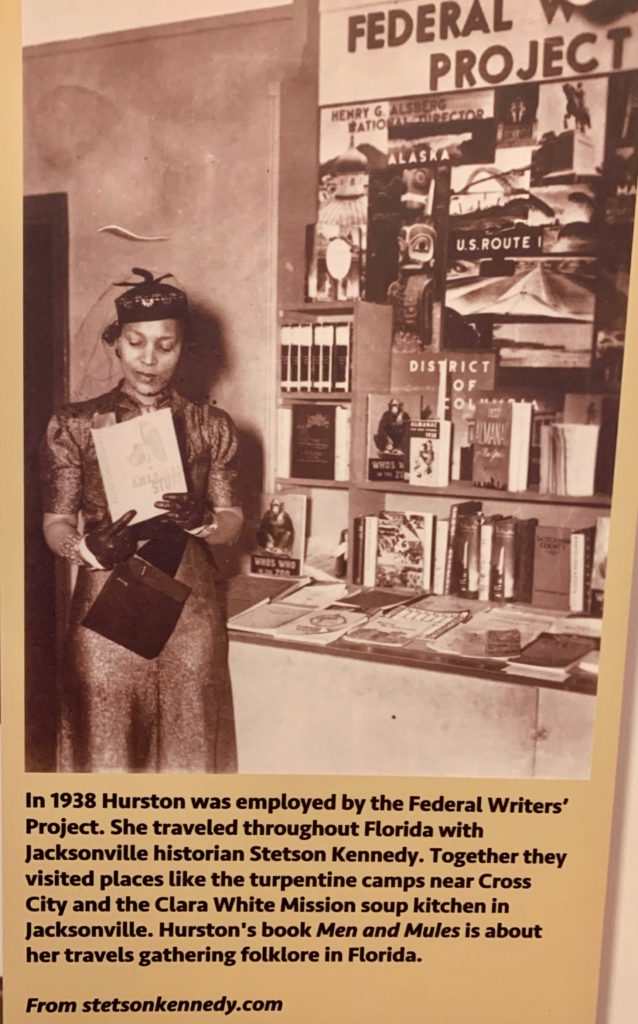

Besides these new perspectives on slavery in Spain and Florida, the Lincolnville Museum offered thoughtful exhibits on Emancipation, Reconstruction and Jim Crow. I loved seeing this display about Nora Zeale Hurston.

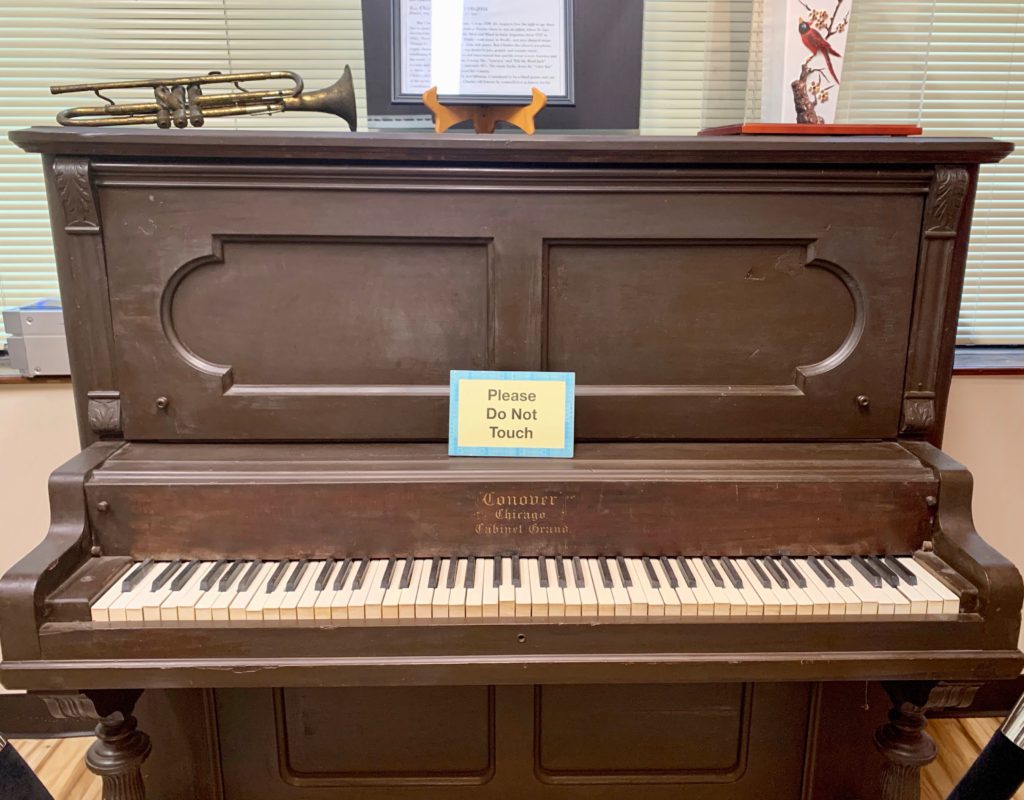

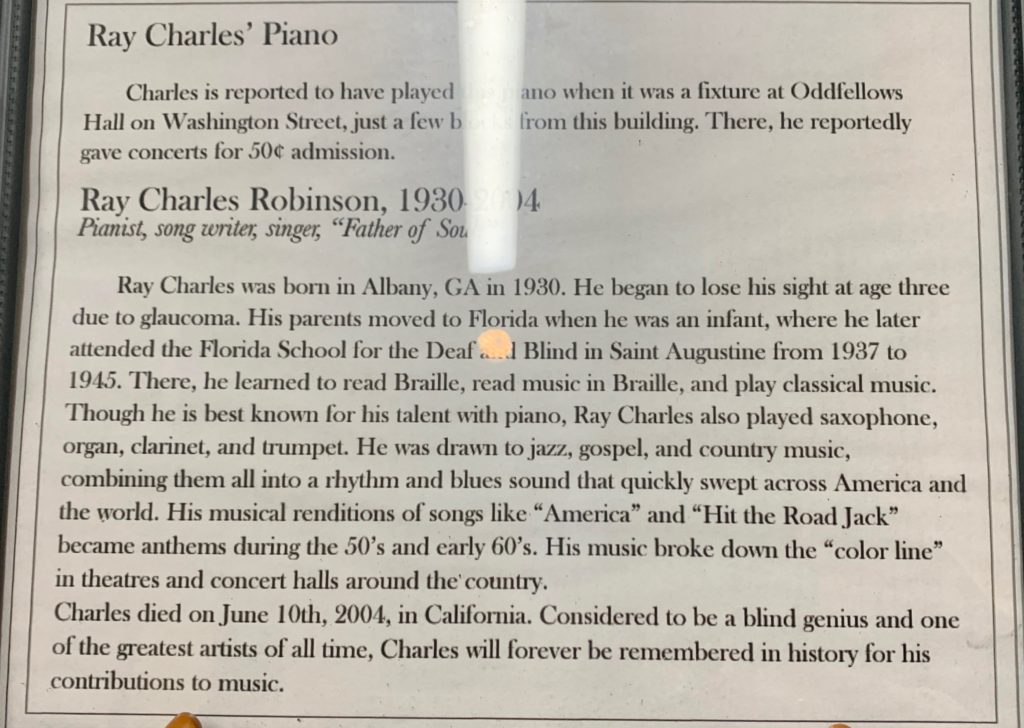

And this one about the one and only Ray Charles.

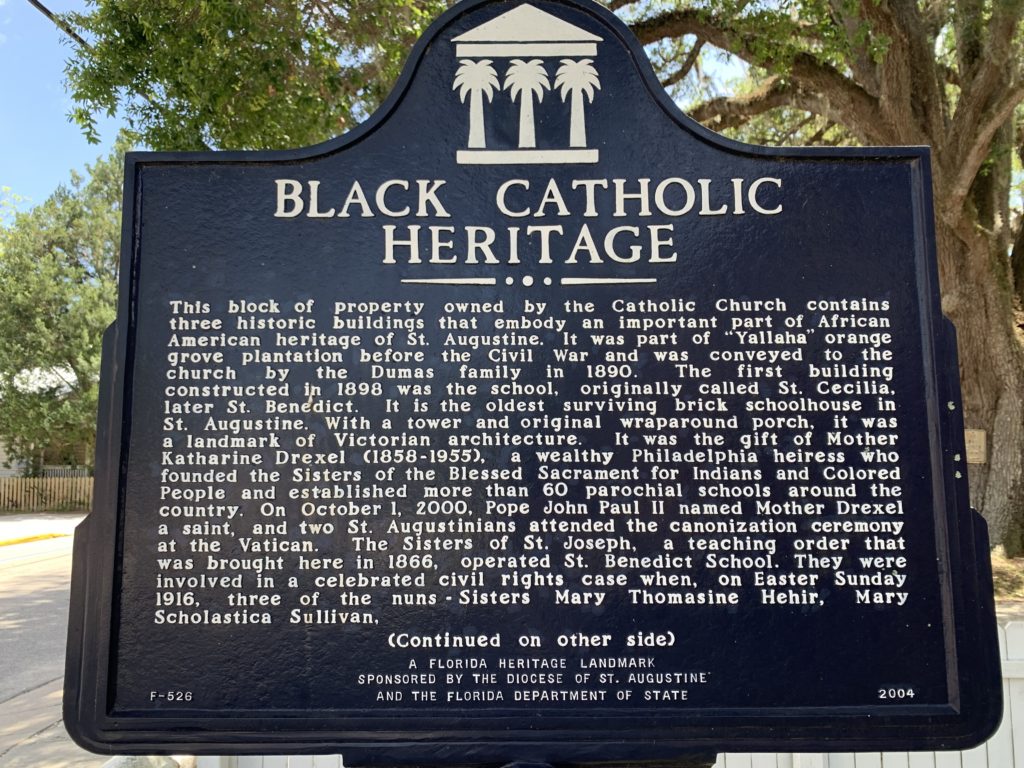

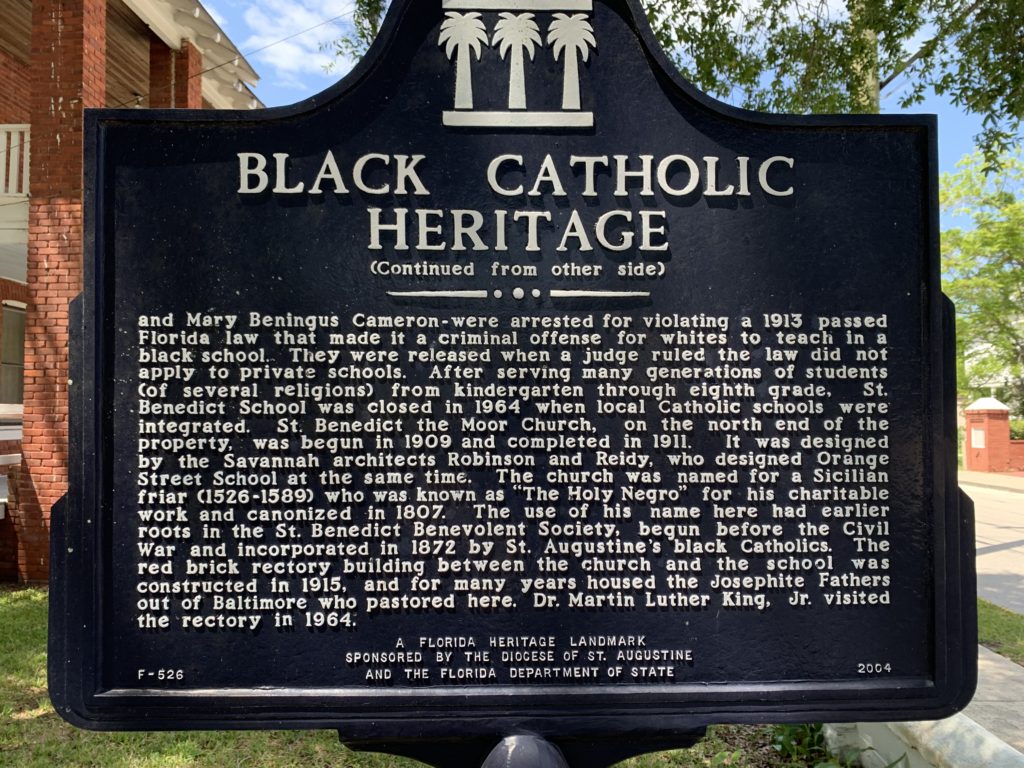

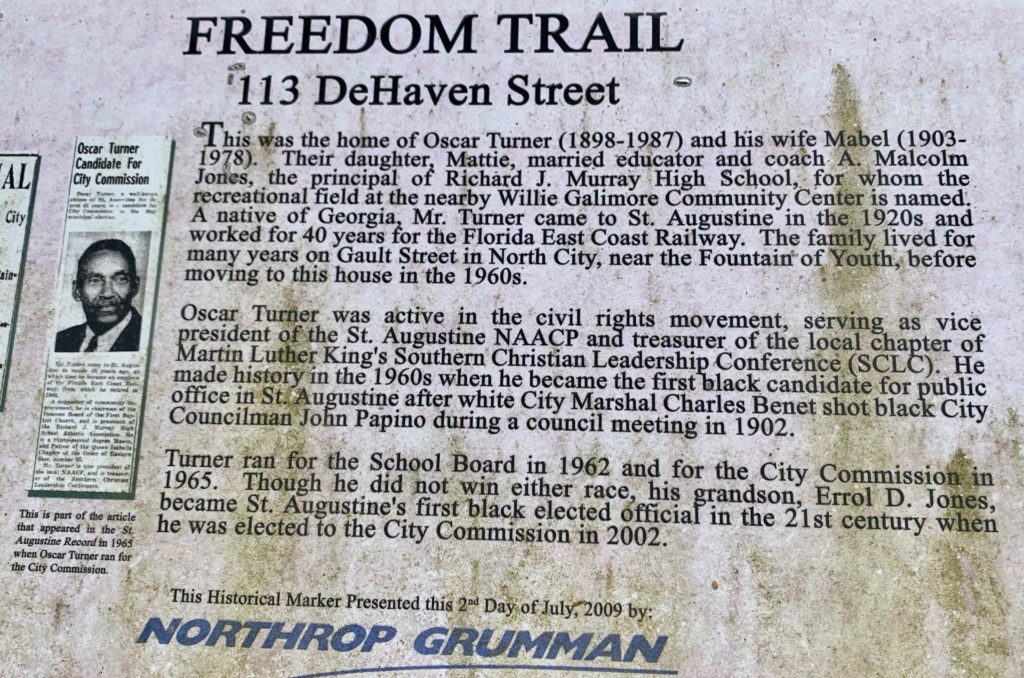

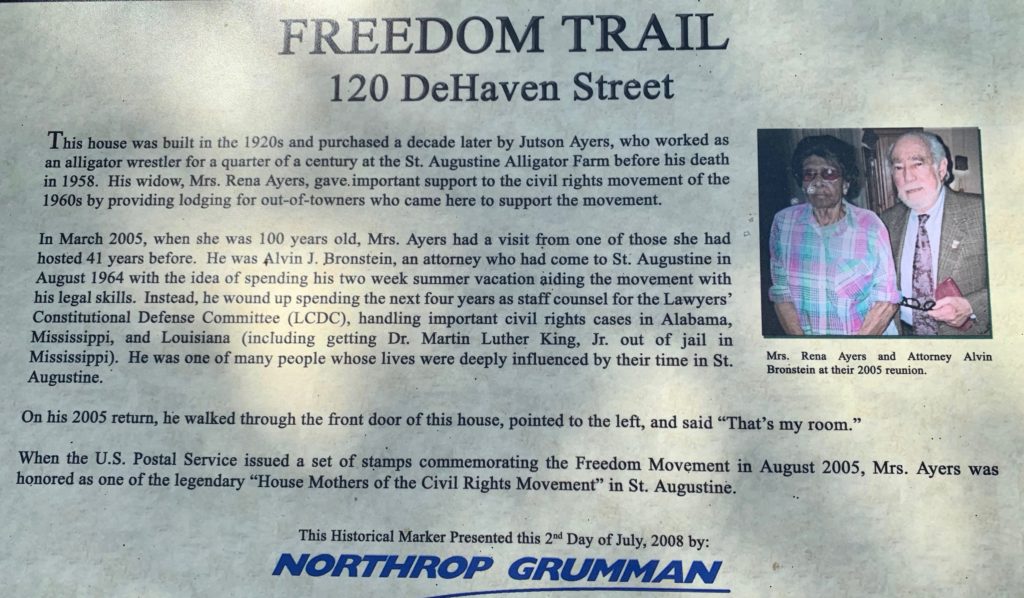

After more than an hour in the museum, we walked through the Lincolnville neighborhood and found many interesting houses, churches, and explanatory markers.

At Dr. Robert B. Hayling Freedom Park, I found art by children and chimes on which I could ring out Freedom for All!

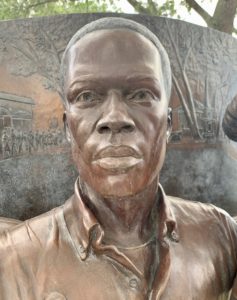

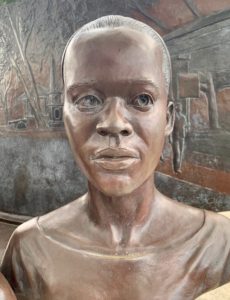

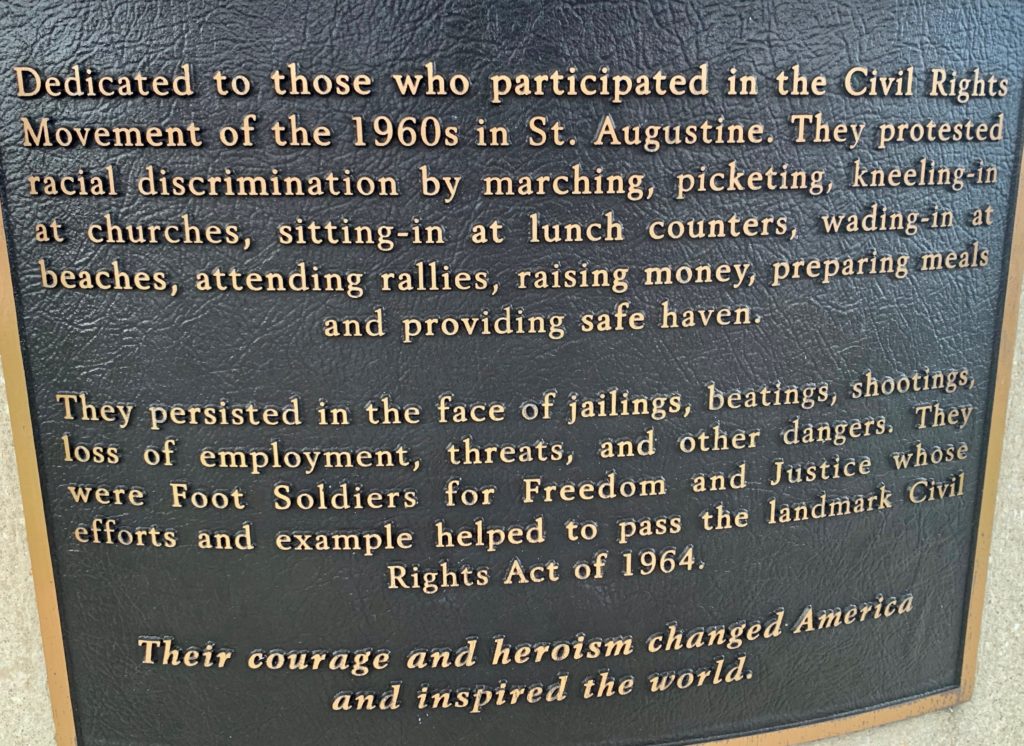

The next day Nina and I visited the downtown Historic District and found the statue dedicated to the St. Augustine Foot Soldiers of the Civil Rights Movement. The 675 lb. bronze monument, designed by sculptor Brian R. Owens of Deltona, Florida, features four life-size portraits of anonymous foot soldiers placed shoulder to shoulder, in front of a relief illustrating a protest in the same Plaza where the monument is now installed. The portraits represent an approximate demographic profile of the foot soldiers: A Caucasian college student, and three African Americans: A male in his thirties, a female in her sixties and a 16-year-old female.

On our last day, Nina took me to the splendid St. Augustine Beach to get a sense of what it could have looked like to the Conquistadors. The wind blew the sand and the waves. Thank you, Nina and Roger for sharing your beautiful city!

Leave a Reply