Historic Georgetown

From 1969 – 71 Steve and I rented a townhouse at 2715 “O” Street N.W. in the Georgetown section of Washington DC. Our half of the house was just 12 feet wide. The lower level kitchen and dining room opened to a small garden. Steve’s office on the top floor doubled as a guest room. I loved being able to walk to my office on Pennsylvania Avenue. Nearby were Dumbarton Oaks, Montrose Park, and many fascinating shops. Before long we became friends with Judith and Stan Morris, who lived on Dent Place. Steve liked playing tennis or basketball at Rose Park, a block east. Four doors west there was a Black church, now known as the Anglican Parish of Christ the King. They were kind to let me practice their piano. A Black family lived across the street. It was the most diverse place I ever lived. Only now am I probing the history of that lovely neighborhood.

From 1969 – 71 Steve and I rented a townhouse at 2715 “O” Street N.W. in the Georgetown section of Washington DC. Our half of the house was just 12 feet wide. The lower level kitchen and dining room opened to a small garden. Steve’s office on the top floor doubled as a guest room. I loved being able to walk to my office on Pennsylvania Avenue. Nearby were Dumbarton Oaks, Montrose Park, and many fascinating shops. Before long we became friends with Judith and Stan Morris, who lived on Dent Place. Steve liked playing tennis or basketball at Rose Park, a block east. Four doors west there was a Black church, now known as the Anglican Parish of Christ the King. They were kind to let me practice their piano. A Black family lived across the street. It was the most diverse place I ever lived. Only now am I probing the history of that lovely neighborhood.

Let me share what I found in the in February 2019 issue of The Georgetowner.

Before the United States and its capital were founded, the Town of George was a bustling colonial port on the Potomac River, dealing mostly with tobacco exports. Slaves worked in the fields and hauled the valuable crop to the docks of Georgetown, Maryland, which was one-third African American around 1750. In the 1800 U.S. Census, Georgetown and close-by land — but not the Federal City proper — had “1,449 slaves and 277 free blacks out of a total population of 5,120,”

The town was a mix of white citizens, free immigrants, indentured servants and free and enslaved blacks, the latter sometimes hired out for work elsewhere. Some did not live in owners’ homes but nearby — in cottages, attics, alleys or shacks. Slave trading was banned in the federal district in the mid-nineteenth century, but the lucrative practice continued in Georgetown. Due to its prosperity, Georgetown had many slave markets and held slave auctions.

An early black visitor to Georgetown was Benjamin Banneker (1731 – 1806), a freeman who helped measure the future District of Columbia boundary lines. He had a farm nearby, located near what is now Ellicott City MD, and would join his colleagues at Georgetown taverns for dinner. At that time, Georgetown was the only built-up place other than Alexandria. On February 15, 1980, during Black History Month, the United States Postal Service issued a commemorative postage stamp that featured a portrait of Banneker, who was also an astronomer who recorded his observations in almanacs published in 1792-93.

An early black visitor to Georgetown was Benjamin Banneker (1731 – 1806), a freeman who helped measure the future District of Columbia boundary lines. He had a farm nearby, located near what is now Ellicott City MD, and would join his colleagues at Georgetown taverns for dinner. At that time, Georgetown was the only built-up place other than Alexandria. On February 15, 1980, during Black History Month, the United States Postal Service issued a commemorative postage stamp that featured a portrait of Banneker, who was also an astronomer who recorded his observations in almanacs published in 1792-93.

The District of Columbia once included Arlington and Alexandria as part as its 10-square-mile diamond of land. When slave trading was about to be banned in the District, Alexandria (which then included Arlington) wanted out. Retrocession was approved by Congress — hence, D.C.’s jagged edge, its map showing the legacy of slavery. Banneker, incidentally, sent Thomas Jefferson a copy of his almanac as a rebuttal to the president’s belief that blacks were not capable of intellectual growth.

Georgetown University, which began classes in 1792, now dominates the skyline west of Wisconsin Avenue. Let us hear from history professor Adam Rothman, a member of Georgetown University’s Working Group on Slavery, Memory & Reconciliation, in 2016, regarding the university’s connection with the Jesuits’ sale of 272 slaves in 1838.

“It seems to me that the story of Georgetown and slavery is a microcosm of the whole history of slavery,” said Since then, the university has apologized for arranging the sale of slaves from D.C. and Maryland farms to help pay off debts that endangered the survival of Georgetown College. And it has renamed two main campus buildings: for Isaac Hawkins, the first slave listed on the sales document; and for Anne Marie Becraft, who founded a school nearby for black girls and later became one of America’s first black nuns. The school has also offered descendants of the 272 slaves, most of whom ended up in Louisiana, legacy status in admissions.

The Rev. Patrick Healy, S.J., who led Georgetown University from 1873 to 1882, improved the school’s academic standing as well as its campus, constructing the building that bears his name with income from property sales up Wisconsin Avenue, at and near McLean Gardens. Called “the Spaniard” in his day, Healy’s mother was black and his father Irish. He was the first black president of a major university — fully acknowledged in the 20th century.

At the turn of the 20th century, many black Georgetowners lived in Herring Hill (named for the fish in Rock Creek) near Rose Park. That’s about where we lived seventy years later. According to “Black Georgetown Remembered”

Blacks and whites lived — and played — side by side in many blocks, although with segregation they did not attend the same schools or churches. Georgetown had lost its luster and seemed lost in time. With the C&O Canal slowly hauling barges of coal, its port long silted up and its waterfront with a rendering plant and a power plant, the town was classified as industrial.

Nevertheless, in the face of segregation and racism, black Georgetowners established a community that included a variety of clubs, sports teams and black-owned businesses. Almost every corner near Rose Park boasted a business.

Tennis doubles champions Roumania and Margaret Peters lived at 2710 O St. and played at the Rose Park clay courts. Rose Park was declared “For Colored Only” by the city in the 1940s. Residents quickly tore down the sign, and the park became one of the District’s first to be integrated. A memorial plaque honoring the Peters sisters was erected there in 2016, paid for by then-Secretary of Homeland Security Jeh Johnson and his wife Susan.

With the expansion of the federal government, new employees needed housing. Affordable Georgetown was close to downtown and a real estate rush began. In 1950, the Old Georgetown Act brought new zoning restrictions. With higher assessments came more taxes. Many homeowners could not keep up.

The black population of Georgetown fell from nearly 30 percent of the general population in 1930 to less than nine percent by the 1960 census, and the racial diversity that had been so much a part of Georgetown’s historical character was virtually lost,

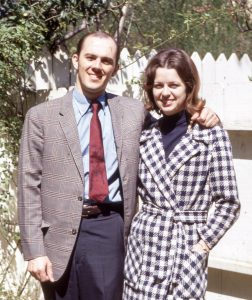

Just look how young we were then. Steve was busy working for the Pentagon, the Department of Health, Education and Welfare, and for a few months in 1971, the Nixon White House. Besides my day job as a researcher at McKinsey & Company, I was busy exploring DC museums. When I got pregnant with Lilli, we found an affordable three bedroom house to rent in nearby Arlington. But we kept coming back to Georgetown to see friends, especially the Morrises, whose daughter Courtney arrived just two months before Lilli. In 1973-74 the girls attended Little Folks School at Dumbarton Methodist Church. The half-a-house of 1,210 square feet that we rented, is still there on “O” Street. Zillow reports that it last sold for $959,000 in June 2018.

Just look how young we were then. Steve was busy working for the Pentagon, the Department of Health, Education and Welfare, and for a few months in 1971, the Nixon White House. Besides my day job as a researcher at McKinsey & Company, I was busy exploring DC museums. When I got pregnant with Lilli, we found an affordable three bedroom house to rent in nearby Arlington. But we kept coming back to Georgetown to see friends, especially the Morrises, whose daughter Courtney arrived just two months before Lilli. In 1973-74 the girls attended Little Folks School at Dumbarton Methodist Church. The half-a-house of 1,210 square feet that we rented, is still there on “O” Street. Zillow reports that it last sold for $959,000 in June 2018.

I heartily recommend this excellent 40-minute video created in 1989, to accompany Jennifer Ortiz’ book, Remembering Georgetown’s Black History, which was re-published in March 2016. Listen to old timers who grew up in Georgetown tell about the schools, the churches, and the sports that they say made them one big family.

Leave a Reply