Bach’s Footsteps

In June 2001, my brother Joel Kirkpatrick and I took a two-week tour In the Footsteps of Bach with the Houston Bach Choir, a trip I recall with great pleasure as I celebrate Bach’s 337th birthday this week. Joel and I were the only non-Houstonians on the tour, but as music lovers, native Texans, and Rice University graduates, we found many kindred spirits. Most of these sixty-seven people knew the facts of Bach’s life by heart and many spoke German well. Twenty-five were professional singers, five were organists, four were composers of works in the Choir’s repertoire, and three were faculty members at Houston’s High School for the Performing and Visual Arts. The rest of us were supporters. It was a fascinating, congenial group of travelers.

In June 2001, my brother Joel Kirkpatrick and I took a two-week tour In the Footsteps of Bach with the Houston Bach Choir, a trip I recall with great pleasure as I celebrate Bach’s 337th birthday this week. Joel and I were the only non-Houstonians on the tour, but as music lovers, native Texans, and Rice University graduates, we found many kindred spirits. Most of these sixty-seven people knew the facts of Bach’s life by heart and many spoke German well. Twenty-five were professional singers, five were organists, four were composers of works in the Choir’s repertoire, and three were faculty members at Houston’s High School for the Performing and Visual Arts. The rest of us were supporters. It was a fascinating, congenial group of travelers.

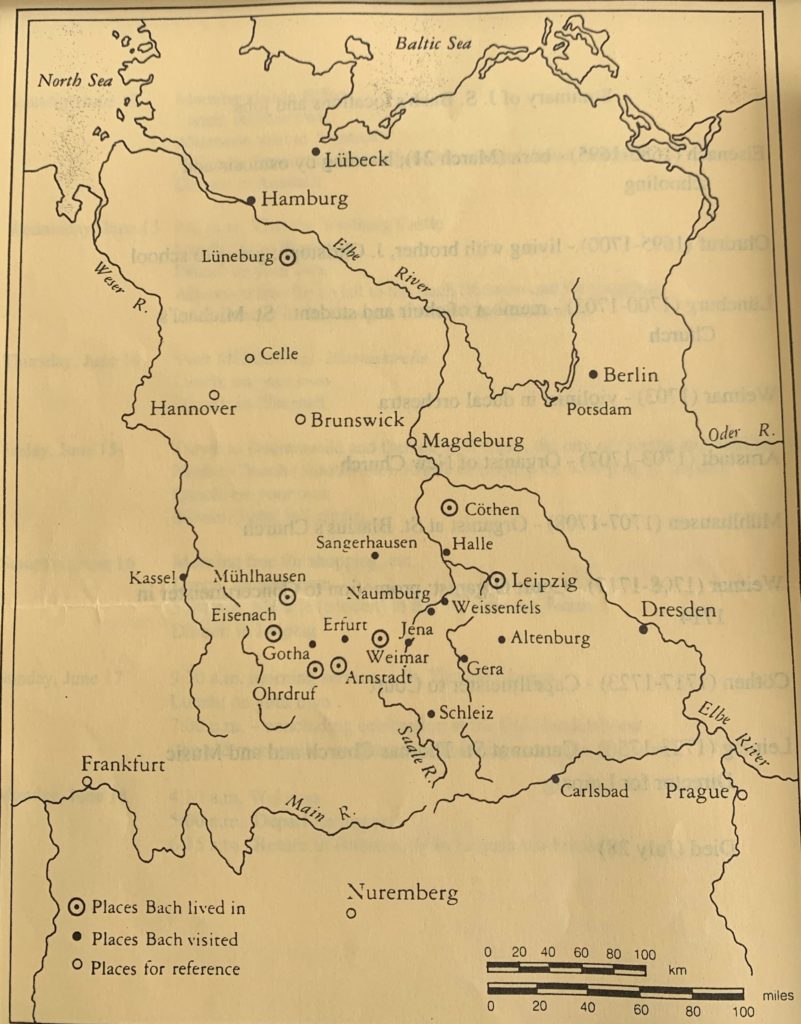

Our journey took us to Bach’s birthplace in Eisenach, to Lüneburg where he spent his late teens, to his first church in Arnstadt, to Mühlhausen, Dresden, and finally to Leipzig, where he died in 1750 at age 65.

Johann Sebastian Bach was born March 31, 1685 to a family of musicians in Eisenach. From an early age he learned to play violin and sang as a chorister in his church. What impressed me most in this small town was how quickly we could walk from his school to his church and to the town hall, where his father and other family members gave concerts at 4 o’clock each afternoon. Eisenach was no bigger than Rivercrest, my neighborhood of a hundred houses in Arlington VA. Bach was unlucky, however. Before he turned ten, both his mother and his father had died. Homeless, he went to live with his oldest brother Christoph, an organist in a nearby town.

Christoph taught him the basics of music composition, but legend has it that he kept from his younger brother a book of pieces by famous composers he thought too difficult. Sebastian, as he was called, managed to get hold of the book and secretly copied the pieces out by moonlight. When his brother found out, he took away the book and the copies, but by then Sebastian knew all the pieces by memory.

By the time Sebastian was fifteen, his brother’s house had become too crowded with younger children. He won a scholarship to the choir school at St. Michael’s Church in Lüneburg in northern Germany, near Lübeck, where our tour began. The only problem was that he had to walk 200 miles to get there. But Bach was resourceful: he slept in haylofts and earned meals by playing his violin at taverns along the way.

Three years later Sebastian returned to Thuringia to start his first job as a church organist in Arnstadt. Shown above is the glorious organ he played, which still sounded wonderful. After serving as a church musician for several years, Bach became Kapellmeister (senior court musician) first for the Duke of Saxe-Weimar and then for the Prince of Anhalt-Cöthen. In these places he had more time to compose. In Weimar he wrote some of his greatest organ works and the beautiful chorale, “Jesu, Joy of Man’’s Desiring.” Here is a recording I made two years ago of Myra Hess’s arrangement of that lovely piece.

Three years later Sebastian returned to Thuringia to start his first job as a church organist in Arnstadt. Shown above is the glorious organ he played, which still sounded wonderful. After serving as a church musician for several years, Bach became Kapellmeister (senior court musician) first for the Duke of Saxe-Weimar and then for the Prince of Anhalt-Cöthen. In these places he had more time to compose. In Weimar he wrote some of his greatest organ works and the beautiful chorale, “Jesu, Joy of Man’’s Desiring.” Here is a recording I made two years ago of Myra Hess’s arrangement of that lovely piece.

Here’s Joel investigating the workings of an old German organ we saw demonstrated in Anhalt-Cöthen. where Bach wrote many instrumental works including the great Brandenburg Concertos. Just when everything seemed perfect, his wife died. Seventeen months later Bach married Anna Magdalena, a professional singer. Their marriage was a happy one that produced 13 children (for a total of 20, but only 10 survived childhood). He dedicated to Anna Magdalena two “notebooks” of music, famous for their minuets.

Here’s Joel investigating the workings of an old German organ we saw demonstrated in Anhalt-Cöthen. where Bach wrote many instrumental works including the great Brandenburg Concertos. Just when everything seemed perfect, his wife died. Seventeen months later Bach married Anna Magdalena, a professional singer. Their marriage was a happy one that produced 13 children (for a total of 20, but only 10 survived childhood). He dedicated to Anna Magdalena two “notebooks” of music, famous for their minuets.

Along the way we marveled at German cultural shrines in Wartburg, Wittenberg, and Weimar. Weimar made me think of Goethe and Schiller, and Wittenberg made me sing with the kids playing recorders. It’s a university town along the River Elbe with close ties to Martin Luther, leader of the Protestant Reformation. A medieval market was in full swing on the main plaza!

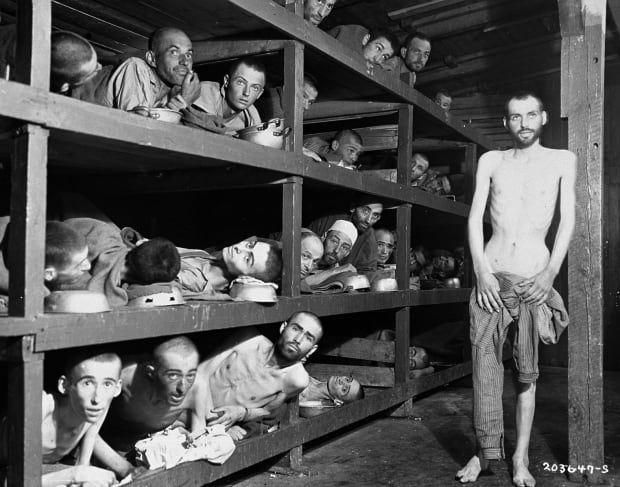

On the way to Weimar we visited Buchenwald Concentration Camp. It was a sobering experience that resonated with Even When God is Silent, an anthem composed by Michael Horvit, a University of Houston professor who was on the tour with his wife Nancy. The lyrics were found scratched on the wall of another camp near Cologne. I was glad to find this recording made on the tour by Joe White, one of the Choir members.

Eastern Germany had shaken loose from the Soviet Union only a dozen years before our tour. Many buildings were painted in a boring shades of gray, but we encountered occasional bright colors, magnificent organs, and many historic buildings

On the long bus ride from Lübeck to Dresden, we sang rounds in German and played word games. One of the Bach experts on the bus told us that on summer camping trips, Bach family members enjoyed seeing how many of their voices they could get to harmonize on a favorite song. Once they counted 27 different pitches that were in harmony throughout the song!

My brother Joel had recently retired after serving many years as a neuropathologist at the Texas Medical Center in Houston. He was now living in Vienna, where his new wife, Elisabeth, was completing her degree in medicine. It was the most time Joel and I had spent together since we were children. I missed celebrating our 35th wedding anniversary with Steve on June 11, but he sent beautiful flowers to Eisenach. It was a pleasure to get to know Sylvia Strong, a piano teacher at the Houston High School for the Performing and Visual Arts. Here we are at a bust of Mendelssohn in Leipzig.

In Dresden, we visited the Frauenkirche, a magnificent church badly damaged in WW II bombing. With contributions from all over the world, it was painstakingly rebuilt and finally reopened in 2005. We attended a concert by the Dresden Bach Choir, which was planning a visit to Washington that September. On September 11, 2001, several neighbors and I were looking forward to welcoming 20 members of the Dresden Bach Choir, who were to give a concert at a local church on September 13. I had found housing for many of the Dresden Choir members with several of my neighbors. But alas, their Lufthansa flight from Germany was turned around over the Atlantic Ocean. We never got to return the hospitality we had enjoyed in Dresden.

In Dresden, we visited the Frauenkirche, a magnificent church badly damaged in WW II bombing. With contributions from all over the world, it was painstakingly rebuilt and finally reopened in 2005. We attended a concert by the Dresden Bach Choir, which was planning a visit to Washington that September. On September 11, 2001, several neighbors and I were looking forward to welcoming 20 members of the Dresden Bach Choir, who were to give a concert at a local church on September 13. I had found housing for many of the Dresden Choir members with several of my neighbors. But alas, their Lufthansa flight from Germany was turned around over the Atlantic Ocean. We never got to return the hospitality we had enjoyed in Dresden.

On June 15 we reached Leipzig, our final destination, where Bach spent the last twenty-seven years of his life directing musical activities at St. Thomas Church. He, his wife Anna Magdalena, and their large family lived next door in a building that also housed the boys choir. It must have been a noisy, but stimulating place. Bach wrote most of his 290 cantatas for this choir. He also wrote large-scale Biblical dramas for choir, orchestra, and soloists. An example is St. Matthew’s Passion, considered old-fashioned after Bach’s time, but revived a hundred years later under the direction of Felix Mendelssohn, who lived in Leipzig and loved Bach’s music. Many now consider it one of his greatest works. [Steve gave me a recording of St. Matthew’s Passion for Christmas six months before we married, convincing me how much he loved me.] Bach, a devout Lutheran, wrote “Soli Deo Gloria”–for the glory of God–at the end of each of his compositions. He is buried near the altar of St. Thom

On June 15 we reached Leipzig, our final destination, where Bach spent the last twenty-seven years of his life directing musical activities at St. Thomas Church. He, his wife Anna Magdalena, and their large family lived next door in a building that also housed the boys choir. It must have been a noisy, but stimulating place. Bach wrote most of his 290 cantatas for this choir. He also wrote large-scale Biblical dramas for choir, orchestra, and soloists. An example is St. Matthew’s Passion, considered old-fashioned after Bach’s time, but revived a hundred years later under the direction of Felix Mendelssohn, who lived in Leipzig and loved Bach’s music. Many now consider it one of his greatest works. [Steve gave me a recording of St. Matthew’s Passion for Christmas six months before we married, convincing me how much he loved me.] Bach, a devout Lutheran, wrote “Soli Deo Gloria”–for the glory of God–at the end of each of his compositions. He is buried near the altar of St. Thom

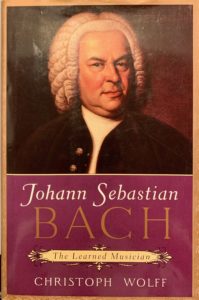

From the 1950’s through the 80’s Communist leaders removed all Christian symbols from the dormitories at St. Thomas and forbid any show of piety by choir members. Since 1992, however, the Church’s mission has been restored and it thrives under the dynamic leadership of Christian Wolff, who is the first cousin of Harvard Professor Christoph Wolff. Christoph Wolff’s biography of Bach was published in 2000. I read it before and after the trip and still refer to it.

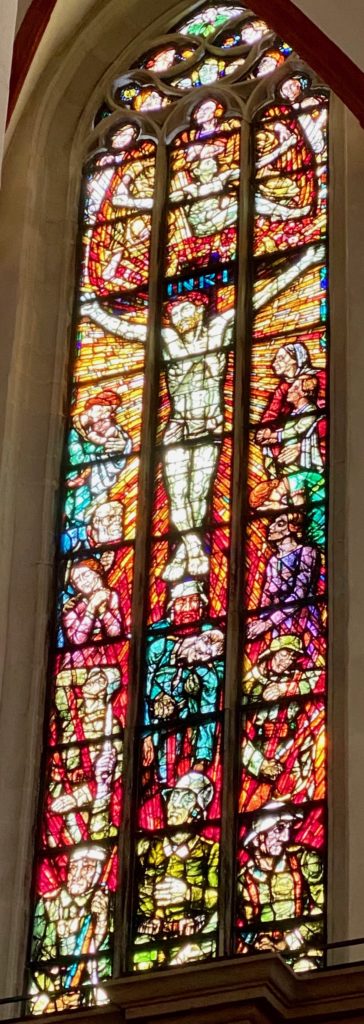

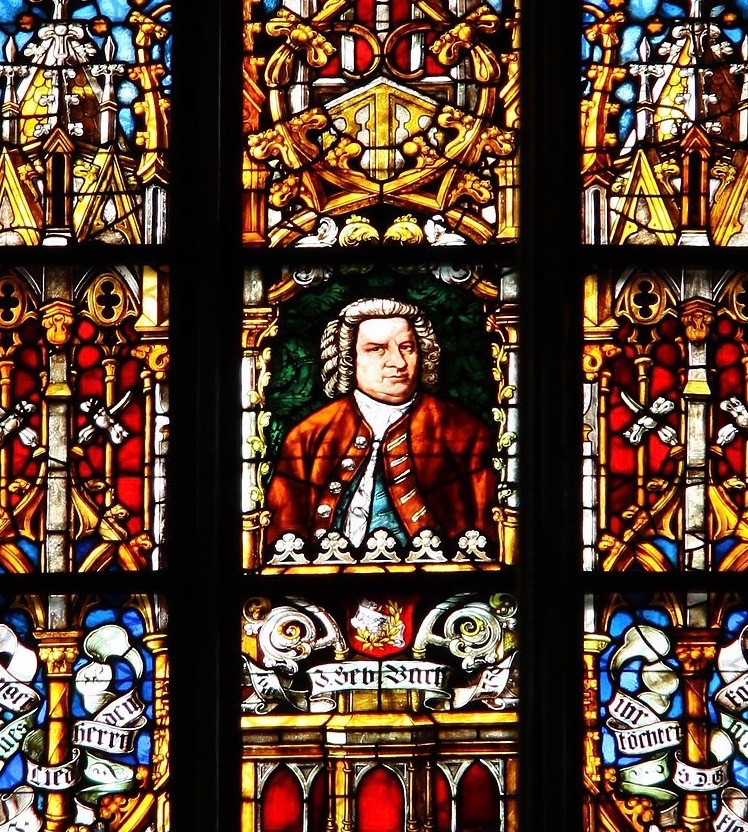

On Sunday, June 17, 2001, our tour leader, Rev. Dr. Robert Moore of Christ the King Evangelical Lutheran Church in Houston, preached the sermon in clear, Texas-accented German. I rejoiced that I could understand most of it, having begun my study of German in high school over forty years before. “Go and be laborers for the Lord,” he preached, “be a shepherd to those in need.” Just now, Pastor Moore proved that he practices what he preaches. Now serving as a Guest Minister at the St. Thomas Church (Leipzig is a Sister City to Houston), he immediately answered my request for a photo of a certain window (see below). He was truly “a shepherd to someone in need.”

The Houston Bach Choir joined the resident choir to fill the sanctuary with Bach’s music. And they sang anthems written by three of the composers who accompanied us: The Christ Hymn, a Cantata for choir and organ by Robert Nelson; Even When God is Silent by Michael Horvit (see above); and during Communion, The Apple Tree by David Ashley White. It was a welcome blend of traditional and contemporary music.

We took communion at the high altar in the Gothic cathedral, just past Bach’s grave. A trio of windows behind the altar were impressive, especially after seeing so many clear glass windows, blankly substituting for the stained glass stories shattered in World War II. Somehow these windows had survived. Portraits of Bach and Mendelssohn, who had both served as Music Directors in this church, centered the windows on either side of one featuring Martin Luther and his Reformation colleagues.

Leave a Reply