Heart of a Woman

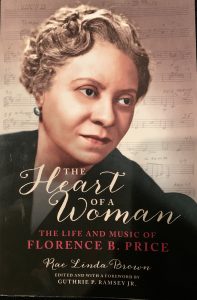

Florence Price was the first Black woman composer to have a work performed by a major symphony orchestra. The Chicago Symphony played her Symphony No. 1 at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1933. She is a woman to whom I can easily relate. She and my grandmother were born in neighboring states, just nine years apart–she in Arkansas, in 1887; my grandmother Raiza, in Texas, in 1878. Like Florence Price, my mother and I both taught piano, raised children, and participated actively in professional associations and churches. But until last summer, I knew nothing about the most widely known African American woman composer from the 1930s to her death in 1953. In segregated Texas, her name was never mentioned. For Christmas, my teacher, Lisa Leonard, and her son Luke Reese, my only piano student, gave me this newly published biography, The Heart of a Woman: The Life and Music of Florence B. Price, by Rae Linda Brown. This carefully researched book has helped me understand her music, her challenges, and through it all, her heart.

Florence Price was the first Black woman composer to have a work performed by a major symphony orchestra. The Chicago Symphony played her Symphony No. 1 at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1933. She is a woman to whom I can easily relate. She and my grandmother were born in neighboring states, just nine years apart–she in Arkansas, in 1887; my grandmother Raiza, in Texas, in 1878. Like Florence Price, my mother and I both taught piano, raised children, and participated actively in professional associations and churches. But until last summer, I knew nothing about the most widely known African American woman composer from the 1930s to her death in 1953. In segregated Texas, her name was never mentioned. For Christmas, my teacher, Lisa Leonard, and her son Luke Reese, my only piano student, gave me this newly published biography, The Heart of a Woman: The Life and Music of Florence B. Price, by Rae Linda Brown. This carefully researched book has helped me understand her music, her challenges, and through it all, her heart.

Price’s music

Rediscovery of Price’s long-neglected larger works is now underway, as Alex Ross writes in the New Yorker. After reading Rae Linda Brown’s detailed accounts of these works, I began to listen to Symphonies No. 1 in E minor and No. 4 in D minor. They are fresh, lively alternatives to the symphonies by European men I’ve heard all my life. Here you can listen to them by the Fort Smith Symphony.

Violin Concertos Nos. 1 and 2, were recorded recently and are now available on Apple Music; the soloist is Er-Gene Kahng, who is based at the University of Arkansas, where Price’s scores are now archived. Here is Marian Anderson’s recording of Price’s setting of My Soul is Anchored in de Lord, which Anderson sang in her famous 1939 concert on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. This week I bought a ticket to the Philadelphia Orchestra’s February 18 virtual concert which featured Michelle Cann performing Florence Price’s Piano Concerto in One Movement. Both the piece and the performer were terrific!

Not until last summer did I discover Price’s work in Piano Music of Africa and the African Diaspora, a five-volume set compiled and edited by William H. Chapman Nyaho. I met Nyaho, dressed in African tribal regalia, at the Music Teachers National Convention in Austin, Texas, in 2006. I bought two of his books then, which I used the next fall when my studio theme was African and African-American music.

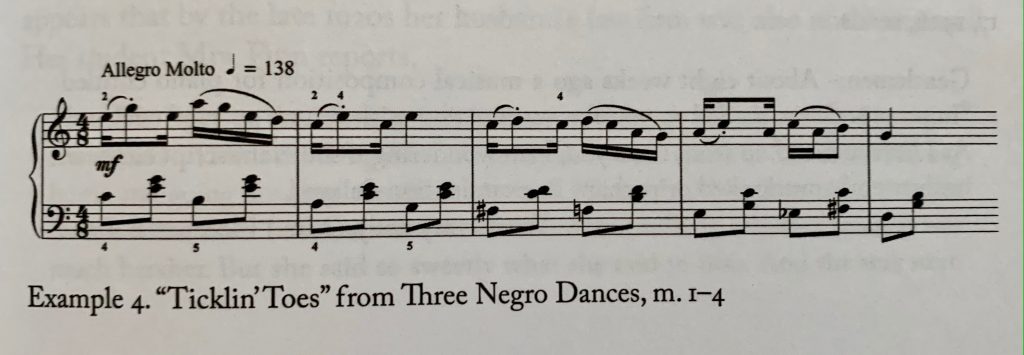

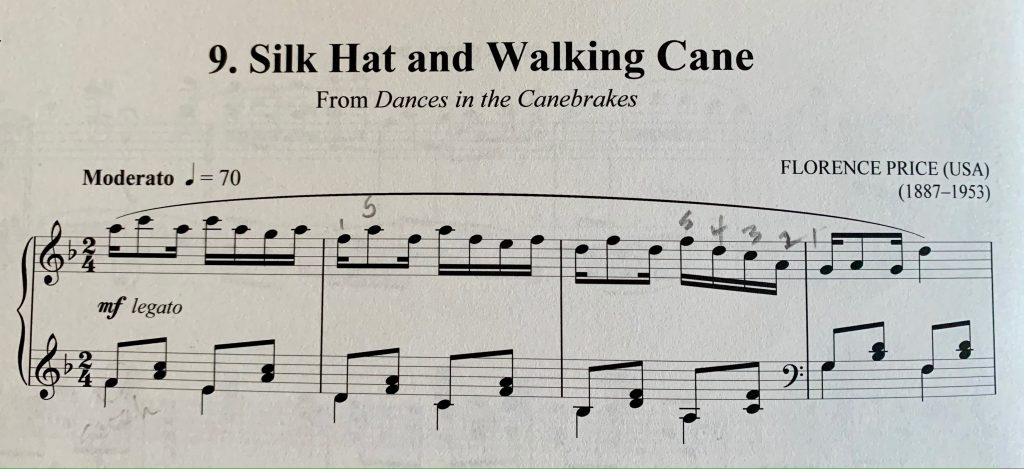

Two of Price’s pieces that I began to practice have similar syncopated (ragtime) rhythms (see below). Before reading Brown’s book, I played them about the same way. My mistake! Ticklin’ Toes is for children and it’s fast! Silk Hat and Walking Cane, as the title implies, is a very elegant dance, in which dancers in formal dress competed for the prize of an elaborately decorated cake. Indeed, the metronome markings show that Ticklin’ Toes should be almost twice as fast as Silk Hat and Walking Cane. Now I play each piece with its unique character in mind. Note: “Cakewalks” were still popular events at fundraisers for my kids’ elementary school in Arlington, Virginia, in the 1980s. By then, the dance had become the less-elegant “musical chairs,” where the last one standing takes the cake.

On Saturday, February 13, I played these two and one more of Price’s pieces, Nimble Feet, in a Black History Month program at the Boynton Beach City Library. Click here for the 47-minute program. I was joined by my student, Luke Reese, and my piano teacher and Luke’s mother, Lisa Leonard, Professor of Collaborative Music at Lynn University in Boca Raton. We had such fun! Luke even donned a silk hat and paraded around the library carrying a walking cane while I played Silk Hat and Walking Cane.

Price’s challenges

Florence Beatrice Smith was born in Little Rock, Arkansas, then known as a “Negro Paradise,” April 9, 1887, toward the end of the Reconstruction period that followed the Civil War. Her family belonged to the small, but significant, Black upper class. Her father, Dr. James H. Smith, became the city’s first Black dentist when he moved there in 1886. Her mother was a businesswoman and a well-trained singer and pianist. For the Smith family, being light-skinned Blacks brought certain privileges–the freedom to move about Little Rock unrestricted and the opportunity to advance economically. But in the 1890s, all Blacks, regardless of their social status, became second-class citizens through a series of Jim Crow laws that stripped them of their basic human rights. By the time Florence left for college in 1903, Little Rock was no more the “Negro Paradise” it once had been.

Florence was only 14 when she graduated as valedictorian of her class at segregated Capitol Hill School in Little Rock. She was accepted at the New England Conservatory, but delayed going all the way to Boston until she was 15, in order to have more time to practice her piano and organ skills. New England Conservatory had a long history of accepting Black students, including, a few years earlier, violinist Joseph Douglass, grandson of Frederick Douglass, and the first Black violinist to make a national tour. At New England Conservatory Florence was nurtured by George Whitefield Chadwick, a composer who directed the Conservatory for many years.

Chadwick invited members of the Boston Symphony Orchestra to serve as private teachers to the students, along with being an inspiring teacher himself. His students described him as “demanding, though fair-minded and witty”. Among his pupils were William Grant Still, Frederick S.Converse, and Florence Price.

Living in Boston and studying with Chadwick opened up a whole new world for Florence. Chadwick treated women in his studio seriously and encouraged them to compose. Even in her earliest compositions, she used melodies from African American folk music. This music was shunned by the Black upper class, but Price embraced it and passionately incorporated it into many of her compositions. Although the normal course usually took four years to complete, Florence completed both the Teachers Diploma in piano and the Soloists Diploma in organ in only three years.

Upon graduation Florence returned to Little Rock. By 1906 the movement to disenfranchise Blacks was complete. Governor Jeff Davis’s advocacy of white supremacy segregated blacks and whites and excluded Blacks from any avenue of political power. Recognizing that she had little chance to teach at any predominately white school in the North and missing her family, she took a job at a Black school in Little Rock. At 19, she felt a sense of responsibility to be of service to the Black community. Black college graduates were so rare that she would enjoy special distinction and be expected to lead. The pay was low: Black teachers were paid $30.36 per month, while white teachers earned $40.52 monthly in Little Rock.

In 1910 Florence’s father died after a short illness. Five months later, Florence, at age 23, decided to leave her hometown and accept a position as Head of the Music Department at Clark University in Atlanta. “Clark welcomed Florence with open arms. At a time when most Black colleges had more white teachers than Black teachers, Clark considered itself privileged to have such a well-educated Negro woman on its faculty.”

While teaching at Clark, Florence stayed in touch with a handsome young attorney in Little Rock, Thomas Jewell Price. During the summer of 1912 she returned to Little Rock to marry him. Despite the institution of Jim Crow laws, Little Rock was still considered a good place for upwardly mobile Blacks. In addition to teaching, Price became president of the Little Rock Club of Musicians, while Thomas Price served as legal advisor to several Black organizations and fraternal groups. Their first child, a son, Thomas Jr., died in infancy.

Losing a child is huge challenge. I well remember how devastating it was for our close friends Claire and Bill Stitt to lose their 15-month-old Jennifer to encephalitis 50 years ago. Claire and I cried many tears together. We were all so happy when another daughter and a son were born. The Prices went on to have two daughters, Florence Louise, born in 1917, and Edith Cassandra, in 1921. Perry Quinney, a student at a nearby college, lived with the family and helped with the children, giving Florence time to teach, compose, and be active in musical groups. Quinney and Price became lifelong friends. I share Florence’s appreciation for long-time friends!

Racial tension In Little Rock became intolerable in the late 1920s. When Price applied to the Arkansas Music Teachers Association, in spite of her impeccable academic and teaching credentials, she was denied admission because of her color. (I served as President of the parallel Virginia Music Teachers Association 2001-03. It, too, was likely segregated 80 years earlier.) Serious about improving her craft as a composer, Price spent the summers of 1926 and 1927 in Chicago studying at the Chicago Musical College.

In late 1927 a young white child was allegedly killed by a black man. Whites wanted to retaliate by killing a “comparable” black child. The apparent victim was to be Florence Price’s youngest daughter. Given that the Price family was one of the most influential Black families in Little Rock, they were an easy target. With no hope that the police would intervene, Florence Price and her two daughters fled to Chicago for safety; they were followed a few months later by her husband. Chicago was considered a land of opportunity and Negroes wanted to escape a section of the country where freedom and equal opportunity were denied them.

In Chicago the Prices found a vibrant African American community. Chicagoans were cultivating every genre of Black music: vaudeville, jazz, blues, gospel, and concert music could be heard in churches, concert halls, Black-owned theaters, and the stage. Price was able to establish herself as a concert pianist and organist, teacher, and composer. She had a gift for writing teaching pieces for children and soon secured publishers.

With the 1929 stock market crash, jobs were hard to come by, even for lawyers. Thomas Price went for long stretches without working. Florence and Thomas Price were already experiencing marital difficulties; the financial strain pushed them to their limits. Florence earned extra money accompanying silent films on the organ, but Thomas’s frustrations led to violence against his wife. Florence was granted a divorce in January 1931. That very month she began work on her first symphony. The next year she entered the Rodman Wanamaker symphony competition and won the top prize of $500.

From 1933 to 1934, Chicago hosted the Century of Progress International Exposition, also known as the Chicago World’s Fair, to celebrate the city’s centennial. Frederick Stock, conductor of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra was appointed Music Advisor. Of the numerous scores he perused for performance at the fair, he was particularly impressed with Price’s Symphony in E Mnor. He chose to premiere the work in the orchestra’s initial series of concerts at the Exposition. The concert in June 1933 was broadcast live on NBC radio. At the conclusion of her symphony, Price, elegantly dressed in a long white gown, was recalled to the stage again and again to acknowledge the long and enthusiastic applause. It marked the first large scale work by a Black woman composer to be played by a major American orchestra. Eugene Stinson, music critic for the Chicago Daily News wrote about this performance of Price’s Symphony in E minor:

From 1933 to 1934, Chicago hosted the Century of Progress International Exposition, also known as the Chicago World’s Fair, to celebrate the city’s centennial. Frederick Stock, conductor of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra was appointed Music Advisor. Of the numerous scores he perused for performance at the fair, he was particularly impressed with Price’s Symphony in E Mnor. He chose to premiere the work in the orchestra’s initial series of concerts at the Exposition. The concert in June 1933 was broadcast live on NBC radio. At the conclusion of her symphony, Price, elegantly dressed in a long white gown, was recalled to the stage again and again to acknowledge the long and enthusiastic applause. It marked the first large scale work by a Black woman composer to be played by a major American orchestra. Eugene Stinson, music critic for the Chicago Daily News wrote about this performance of Price’s Symphony in E minor:

It is a faultless work cast in something less than modernist mode and even reminiscent at times of other composers who have dealt with America in tone. But for all its dependence upon the idiom of others, it is a work that speaks its own message with restraint and yet with passion. Miss Price’s symphony is worthy of a place in the repertory.

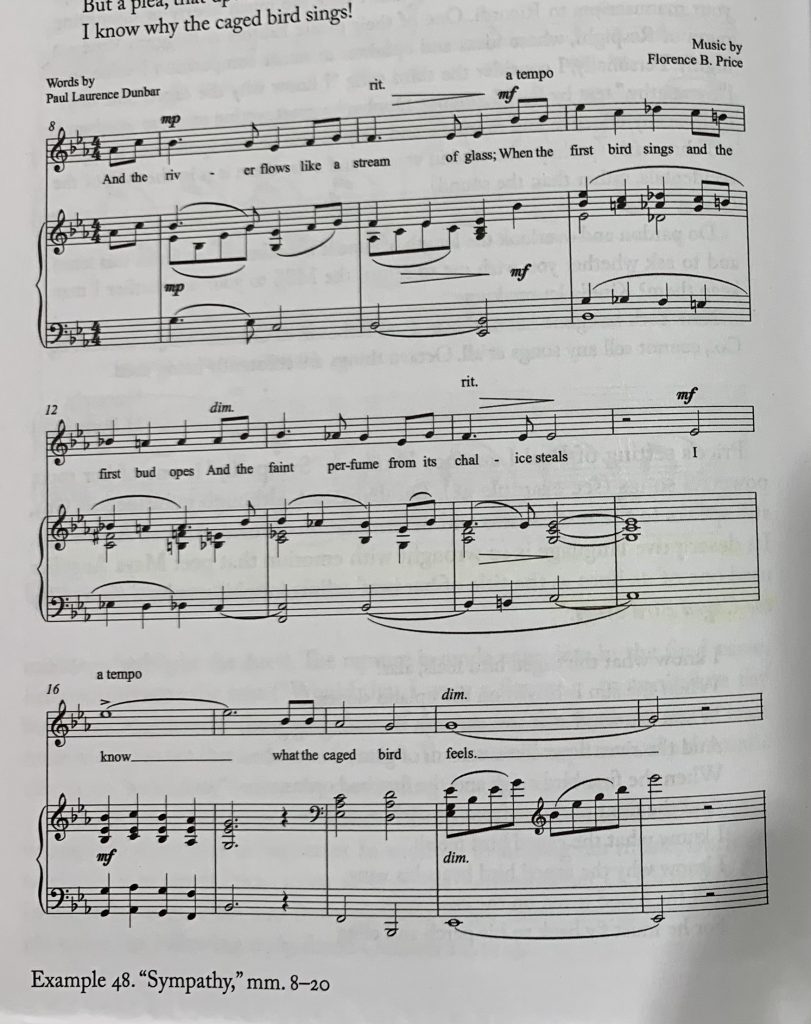

Price continued to write large-scale works during the 1940s and until her death in 1953, composing more symphonies, two violin concertos, chamber works, art songs (poems set to music), and arrangements of spirituals. One of her most provocative art songs is her only setting by a Black woman poet:

The Heart of a Woman

by Georgia Douglas Johnson

The heart of a woman goes forth with the dawn,

As a lone bird, soft winging, so restlessly on,

Afar o’er life’s turrets and vales does it roam

In the wake of those echoes the heart calls home.

The heart of a woman falls back with the night,

And enters some alien cage in its plight,

And tries to forget it has dreamed of the stars

While it breaks, breaks, breaks on the sheltering bars.

Rae Linda Brown writes why she chose the title of this song as the title of her book:

In the entire 25-measure song in E-flat, the tonic (home tone), is only briefly alluded to. The harmony and the vocal line seem to wander aimlessly. The fluid piano accompaniment and the several meter and tempo changes propel the music forward seamlessly. It is Price’s utter intimacy with the poem that qualifies it as one of her most powerful settings.

Price’s song is poignant. The feelings of a “caged bird,” pained in its trapped existence and the confession of broken, shattered dreams is vividly portrayed. Could this be the veiled autobiographical revelation of the composer herself, echoing that of the despaired poet? This inference might give the reader pause to recount Price’s childhood ambition of becoming a doctor, following in her father’s footsteps. And although she was far more successful in her career than even she anticipated, there were professional aspirations that went unfulfilled, and as a single mother she lived in aloneness.

I knew I had seen that title before. Sure enough, I pulled off my bookshelf The Heart of a Woman by Maya Angelou. It was inscribed by my husband as a present for Christmas 1981. This book is the fourth volume of her autobiography, which began with I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings. And that title itself is a line from the poem, Sympathy, by Paul Laurence Dunbar, that Florence Price also set to music.

Fast forward to Inauguration Day 2021. Poet Amanda Gorman wore a ring that featured a bird in a cage. The ring had been given her by Oprah Winfrey. Now I see that this birdcage ring links five remarkable women with huge hearts, who have overcome formidable challenges: poet Georgia Douglas Johnson, Florence Price, Maya Angelou, Oprah Winfrey, and poet Amanda Gorman. I will have them in mind as I continue to play and listen to the music of Florence Price.

Leave a Reply