Museums Matter

On March 9, 2017 I discovered how much museums can matter. At 6:30 that morning, I went online to get four timed passes to the new and very popular National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington DC. The passes (all claimed by 7:00 am) were for my hosts, Powell and Joanne Hutton, my friend Carol Starr, and myself. I had flown in the day before for dinner and discussion with my Arlington Reading Friends. Joanne, a member of that group, and Carol, a dear friend from Rice, both graduated from Alamo Heights High School in San Antonio, but had never met. We four had a lovely lunch at the Museum’s Sweet Home Café.

On March 9, 2017 I discovered how much museums can matter. At 6:30 that morning, I went online to get four timed passes to the new and very popular National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington DC. The passes (all claimed by 7:00 am) were for my hosts, Powell and Joanne Hutton, my friend Carol Starr, and myself. I had flown in the day before for dinner and discussion with my Arlington Reading Friends. Joanne, a member of that group, and Carol, a dear friend from Rice, both graduated from Alamo Heights High School in San Antonio, but had never met. We four had a lovely lunch at the Museum’s Sweet Home Café.

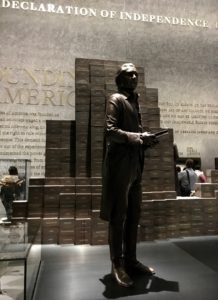

Then we plunged into the powerful exhibits on the subterranean floors of the Museum, which unrolled the dark history of slavery and entrenched inhumanity. Suddenly I saw Thomas Jefferson in new, dimmer light. I had read biographies of him; my daughters had attended the University he founded; Steve had belonged to Farmington Country Club, whose original house Jefferson designed. But I had never considered his likeness against a background of 609 blocks, each representing a slave he had owned.

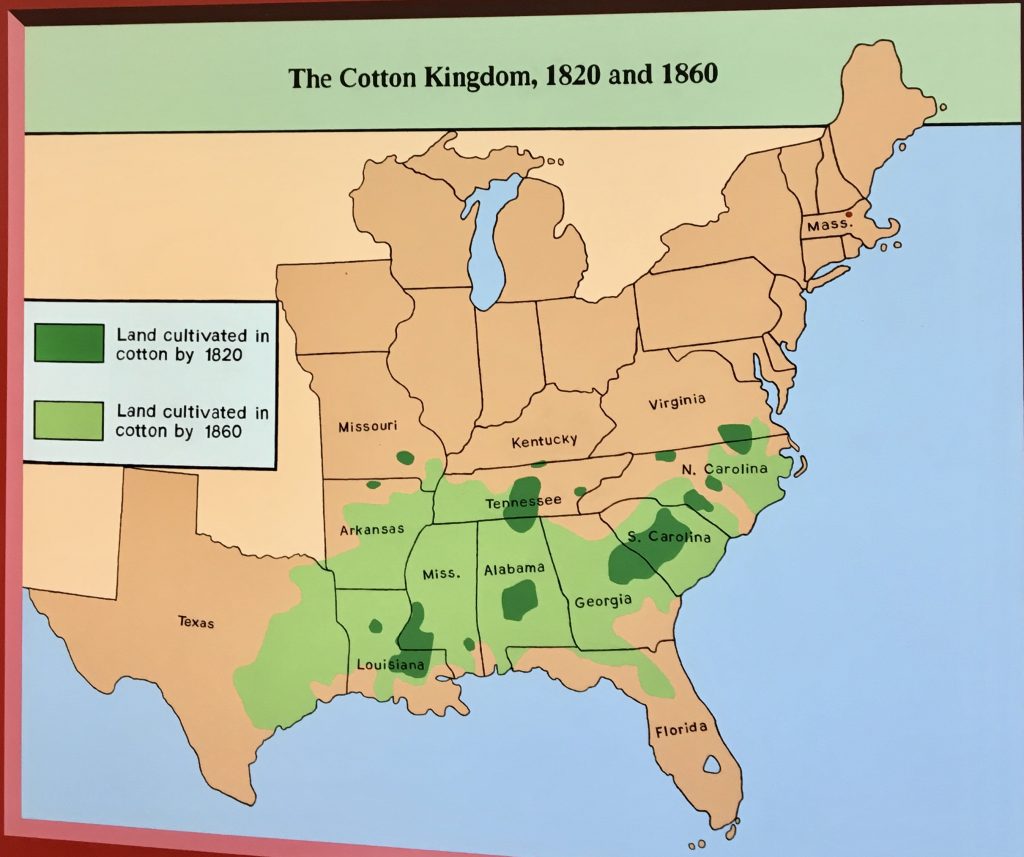

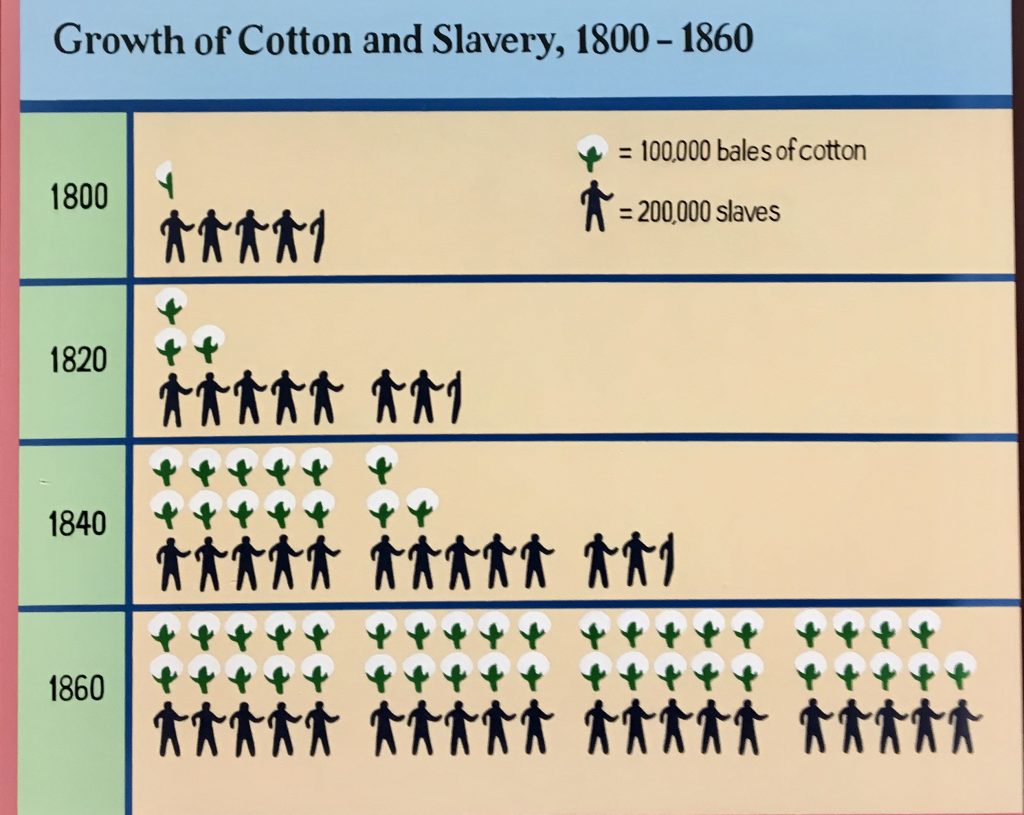

My grandfather operated a cotton gin in Woodson TX, but I never realized how heavily King Cotton weighed on those who planted and picked it. Two years ago, I visited a restored Cotton Mill in Lowell, Massachusetts on a field trip with my granddaughter’s fourth grade class. Exhibits there showed the kids the tedium of picking seed from cotton bolls and taught me how the demand of the New England mills for cotton fueled the growth of slavery in the South:

No wonder a key exhibit at the African American Museum was “King Cotton.” There was so much I never learned about slavery and its repercussions. I had lived through the 1960s Civil Rights marches, but failed to understand their urgency. Wow! This place challenged my education, my heritage, and my Christian faith.

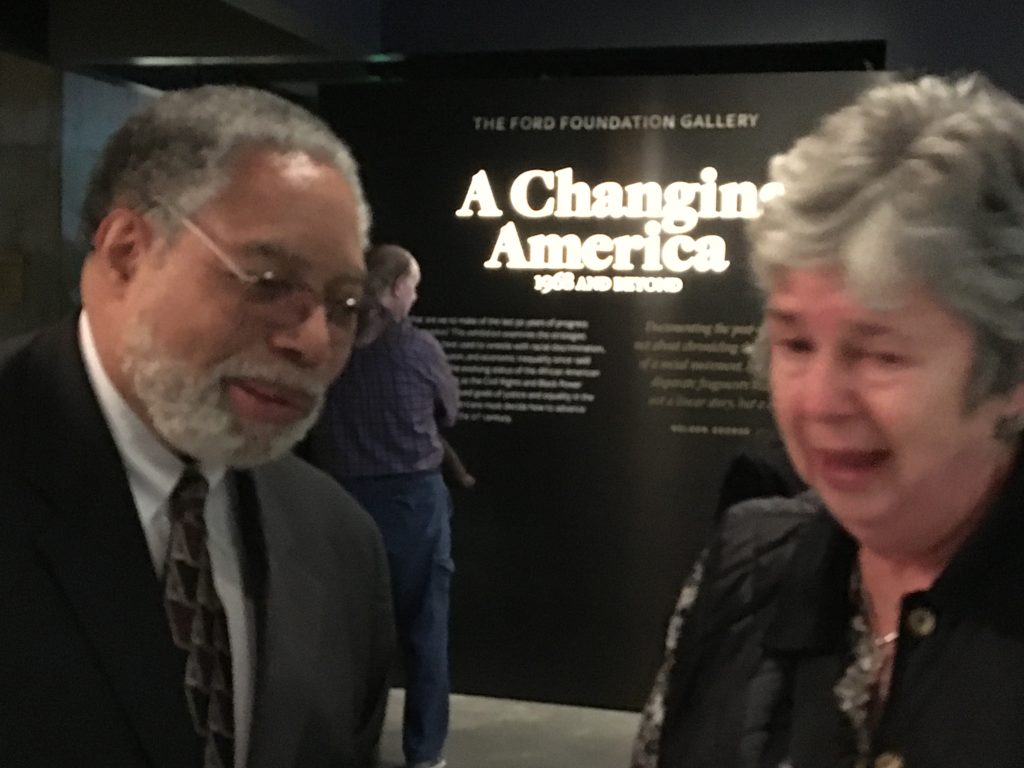

With swirling emotions, I heard a guard’s walkie-talkie report a “high-value party.” Soon I saw a man I recognized from news reports as Lonnie G. Bunch III, the Director of the Museum. He was bidding farewell to a group of nicely dressed people, easy to construe as donors. As he turned to depart, I asked if I could express my appreciation, then spontaneously burst into tears. “I feel so ashamed,” I blubbered. A member of the donor group, sensing a special moment, took my phone from my hand, and snapped this picture.

In response to my distress, Bunch acknowledged my feelings and gently stated the Museum’s central mission, “to help us better understand who we are as Americans and point us toward a better tomorrow.” What an emotional roller coaster was March 9, 2017–-a delicious lunch introducing old and new friends, horror at how slavery uprooted and devalued human beings, sorrow at the trials endured–then, miraculously, consolation from the Director himself. And ever since, a nagging feeling that I should keep striving for a better America.

The Museum was not all dark. Ramp by ramp we climbed to displays of escape, resistance, and cultural contributions. When I returned in 2018 with Elizabeth Lodal, we concentrated on the higher floors, where the encompassing grillwork allows spectacular views of the Mall. The mood became ever more hopeful as galleries of art, music and sports achievements conveyed exultation: “See what we can do!” Last year Steve and I met the Crosspointe Safety Patrols there and were thrilled to see how they appreciated both dark and light aspects.

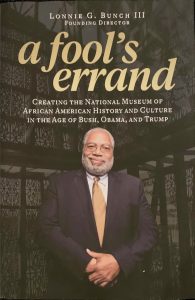

Now in the wake of Black Lives Matter protests, I’m reading Dr. Bunch’s recent book, A Fool’s Errand: Creating the National Museum of African American History and Culture in the Age of Bush, Obama, and Trump. A year ago Bunch became Secretary of the Smithsonian, overseeing 19 world-class museums, 21 libraries, galleries, gardens, and a zoo. It’s hard to imagine how he found time to write this book, but I’m glad he did. It’s simply fascinating!

As early as 1915 African American veterans of the Civil War had sought a memorial in Washington to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the war’s conclusion; World War One intervened. In 1929 Congress pass a law to support the creation of the “National Negro Monument,” but it required nonfederal fundraising; the Great Depression intervened. Efforts for Federal funds in the 1980s and 90s were blocked by powerful Southerners. Finally, in November 2003, with a Congessional effort led by Civil Rights hero and U. S. Representative from Georgia John Lewis, the “National Museum of African American History and Culture Act” was signed by George W. Bush. Lonnie Bunch, who had worked at the National Air and Space Museum for thirteen years and headed the Chicago History Society for five years, was named Founding Director in 2005.

In just eleven years, Bunch got the job done. The museum opened September 24, 2016. Bunch put together a plan, a staff, and a Council. He befriended Congresspeople, collaborated with other Smithsonian Museums, selected architects, planned exhibits, collected stories and artifacts, and raised lots of money. Candid about triumphs and errors, his story comes alive with personalities as vivid as Oprah Winfrey and Quincy Jones. Traveling hundreds of thousands of miles, he listened to museum experts and prospective visitors. A shoeshine man in the Dallas Airport, recognized Bunch as “that Museum guy,” refused payment, and made a memorable statement: “I’m not sure what is in a museum, but it may be the only place where my grandchildren will learn what life did to me, and what I did with my own life.”

Building a new museum on the National Mall invited criticism and complaints. A Florida friend told me that that Museum had ruined the view of the Washington Monument she once had from her office in the Department of Commerce. The lead architect was a British citizen born in Tanzania, Sir David Frank Adjaye. Some complained that they should have chosen an American, not a Brit. It was Adjaye, with his knowledge of Yoruba culture, who conceived the distinctive external feature of the building, called–yes, the Corona! Bunch describes how it evolved.

The crown-like shape was influenced by a tiered post used to support a protective covering for royalty, specifically a wooden architectural column carved by Olowe of Ise in the early twentieth century. Its beautiful form, angled upward to mimic arms raised in prayer, and bronze color made the building memorable…..David wanted to use a computer to plan for random interventions into the skin of the Corona. I was concerned that the Corona was a symbol that read African. So I suggested that we should find a way to use the designs on metalwork in Charleston and New Orleans, decorative features that graced the mansions of the elite, that were made by African American craftspeople, both enslaved and free, in the era prior to the Civil War. Everyone on the design team embraced this idea and the collaboration led to a signature feature that nodded to Africa, but also remembered and honored the fact that so much of America was built by African Americans whose labor was never recognized.

Bunch exercised patience, diplomacy, and street smarts to keep a growing staff focused on the four pillars of this museum:

- a place of memory and meaning

- a lens to better understand what it means to be an American

- a global context for African American history and culture

- collaboration with other museums in DC and many states

During the first year the Museum was open, a 22-minute orientation film by Ava DuVernay was shown continuously. Listen as DuVernay explains why she chose the title, August 28:

Following the death of George Floyd, Bunch has been in demand. I saw him on Meet the Press on June 14. Alerted by Joanne Hutton, who was with me on March 9, 2017, I listened to Bunch being interviewed on Juneteenth 2020. His deep knowledge of African American history, his warm civility, and his careful optimism shine through this 30 minute video:

As statues of Confederates topple and names are changed on schools across the country, the National Museum of African American History and Culture and its fellow museums are more important than ever in deepening our understanding of race. Museums like the DuSable Museum in Chicago, the American Jazz Museum in Kansas City, the African American Museum in Dallas, and the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland, can provide memory, meaning, and context. Simply click on the links and see what these five museums have to offer us, in person or online, during this tumultuous time. As Bunch told me three years ago, museums can “point us to a better tomorrow.”

UPDATE: In September 2020, my friend Marjo took me to two museums in Ohio that taught me more. Click on these links for photos from the Underground Railroad Museum in Cincinnati and the National Afro American Museum in Wilberforce. So much to learn!

The title of Bunch’s book is borrowed from a book he read in an undergraduate history course, Albion W. Tourgée’s, A Fool’s Errand: A Novel of the South During Reconstruction. Tourgée was an abolitionist lawyer who ventured South during Reconstruction to help ensure that the former Confederate states would return to the Union in a manner that would guarantee that the formerly enslaved would have the rights and the protections granted all citizens. Instead, he witnessed violence and intimidation. Upon returning North, he wrote a novel to express his frustrations, but also his hopes that there would one day be a fair and freer South. To Tourgée, a “fool’s errand” was worth the risk, the fear, and the costs, because it was a noble cause that could help a nation heal. Bunch had a very difficult job, that required constant travel and many sleepless nights, but felt that it was worth it to help our nation heal.

The title of Bunch’s book is borrowed from a book he read in an undergraduate history course, Albion W. Tourgée’s, A Fool’s Errand: A Novel of the South During Reconstruction. Tourgée was an abolitionist lawyer who ventured South during Reconstruction to help ensure that the former Confederate states would return to the Union in a manner that would guarantee that the formerly enslaved would have the rights and the protections granted all citizens. Instead, he witnessed violence and intimidation. Upon returning North, he wrote a novel to express his frustrations, but also his hopes that there would one day be a fair and freer South. To Tourgée, a “fool’s errand” was worth the risk, the fear, and the costs, because it was a noble cause that could help a nation heal. Bunch had a very difficult job, that required constant travel and many sleepless nights, but felt that it was worth it to help our nation heal.

The book’s subtitle, naming three U.S. Presidents, reveals how complicated his work became. After George W. Bush signed the enabling legislation, First Lady Laura Bush directed cash left over from the Second Inaugural to the Museum in 2005. In 2009, she agreed to serve on the Museum’s Board. Bunch comments: “While Bush never explicitly connected the development of the museum to his fractured relationship with the black community after Hurricane Katrina, I learned from others in the White House that supporting the museum was a point of pride for the president and first lady.”

After Barack Obama was elected in 2008, a political pundit expressed to Bunch disappointment that the NMAAHC was no longer needed. “He believed that the election of Obama signaled the dawn of a post-racial America, where race no longer mattered.” In fact, President Obama had to thread the needle of racial politics. Proudly African American, he needed to counter the notion that he was president of a single community. His public endorsement, though visible, was not as vocal as that of the Bush administration. However, he told Bunch many times that he “wanted to see this museum open while I am still in office.”

Obama took part in the groundbreaking ceremony for the Museum on February 22, 2012. He concluded his remarks by mentioning Sasha and Malia:

I want my daughters to see the shackles that bound slaves on their voyage across the ocean and the shards of glass that flew from the 16th Street Baptist Church, and understand that injustice and evil exist in the world. But I also want them to hear Louis Armstrong’s horn and learn about the Negro League and read the poems of Phillis Wheatley. And I want them to appreciate this museum not just as a record of tragedy, but as a celebration of life.”

Bunch observed that Obama’s comments captured the spirit of the museum, the power of a people, and proved an emotional experience for all in attendance.

Donald Trump wanted to tour the Museum on the holiday celebrating Martin Luther King Jr., just before his inauguration, but insisted that the museum be closed to the public. Shutting out visitors on the first King holiday since the opening of the museum was not something Bunch could accept, so he offered a day in February.

When Trump arrived, he greeted the Smithsonian contingent warmly and expressed how much his wife Melania had enjoyed the tour I provided her and Mrs. Sara Netanyahu, wife of the Israeli prime minister, two weeks earlier. As we descended via elevator into the History Galleries, I tried to engage President Trump by explaining that the slave trade was the first global business and how its impact reshaped the world in ways that still resonate today.

As we approached a section that examined how nations like Portugal, England, and the Netherlands profited immensely from transporting and selling millions of Africans, the president paused to read a label that discussed the role of the Dutch in the slave trade. For a moment I thought he was paying attention to the work of the museum. He quickly proved me wrong. As he turned from the display, he said to me, “You know, they love me in the Netherlands.” All I could say was let’s continue walking. When Trump tweeted about his visit, he called the museum and me “amazing.” I will take what victories I can get.

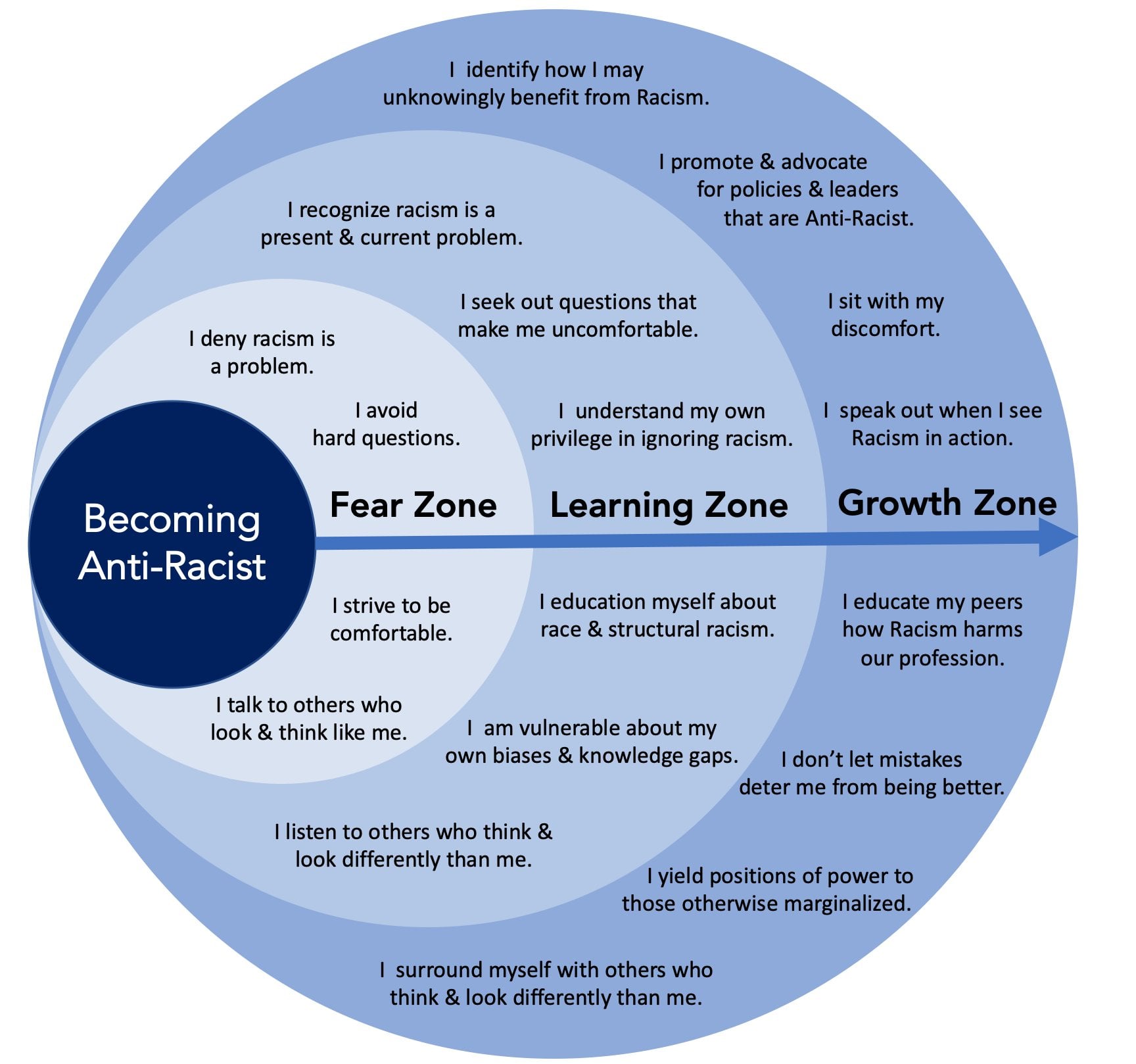

Three years after March 9, 2017 I still feel that I should be striving harder for a better tomorrow. I am committed to tutoring second graders in reading and raising money to send 5th graders to Washington. Please let me know about museums and books that matter to you. I’m starting a list of places to visit once we’re free to travel. Meanwhile, here is a graphic I am contemplating. (Extra points if you find a grammatical error.)

More on this subject from July 4, 2020 New York Times: Smithsonian Director Says “Museums Have a Social Justice Role to Play.”

UPDATE: on June 18, 2001, Gay Yelverton and I parked on the Mall and walked seven blocks to the African American Museum, hoping that we might get passes that are sometimes distributed at noon. As we stood in line, we chatted with some women who lived in DC and often visited the Museum. When they heard we were from Florida, they offered us the passes they had obtained weeks before! Sweet Home Cafe was closed, but we spent two hours seeing many interesting exhibits. We will always remember the generosity of these women.

UPDATE: on June 18, 2001, Gay Yelverton and I parked on the Mall and walked seven blocks to the African American Museum, hoping that we might get passes that are sometimes distributed at noon. As we stood in line, we chatted with some women who lived in DC and often visited the Museum. When they heard we were from Florida, they offered us the passes they had obtained weeks before! Sweet Home Cafe was closed, but we spent two hours seeing many interesting exhibits. We will always remember the generosity of these women.

Leave a Reply