St. Louis Rocks!

What a thrill to spy the Gateway Arch as soon as we entered the city of St. Louis, Gateway to the West! Even more thrilling was to take a trolley car up to the top and look out over both Missouri and Illinois. With a timed ticket I bought in advance, I joined a group of 30+ people who were divided into groups of three to five for the eight trolley cars; there was a nice couple from Florida in my car. It took four minutes to ascend 630 feet to the top. Our group was allowed ten minutes to look out the high windows, which were about 3 feet tall and 9 feet wide.Then we boarded the same trolley cars we had ridden up for a three-minute ride back down. This movie provides more details; my photos follow.

What a thrill to spy the Gateway Arch as soon as we entered the city of St. Louis, Gateway to the West! Even more thrilling was to take a trolley car up to the top and look out over both Missouri and Illinois. With a timed ticket I bought in advance, I joined a group of 30+ people who were divided into groups of three to five for the eight trolley cars; there was a nice couple from Florida in my car. It took four minutes to ascend 630 feet to the top. Our group was allowed ten minutes to look out the high windows, which were about 3 feet tall and 9 feet wide.Then we boarded the same trolley cars we had ridden up for a three-minute ride back down. This movie provides more details; my photos follow.

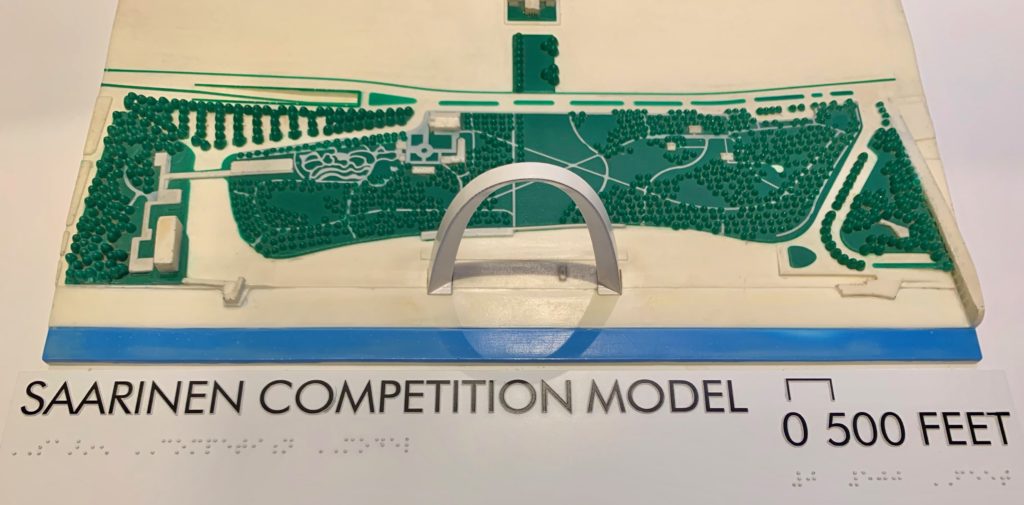

In the spacious, underground National Park Visitors Center, we watched a fascinating 28-minute documentary, Monument to the Dream, that shows how the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial was constructed. It was a triumph of engineering. It was also a triumph of Eero and Lily Saarinen’s artistic vision.

Another thrill was to take a riverboat cruise on the Mississippi River, watching the Arch as the light changed that afternoon.

The next morning we visited the History Museum in Forest Park, an area west of downtown that is larger than Central Park in New York. There I became aware of the city’s remarkable history, confirmed by these excerpts from the city’s website:

- The area that would become St. Louis is located on the traditional, ancestral, and unceded territory of the Illini Confederacy, a group of 12–13 Native American tribes in the upper Mississippi River valley of North America. At the time of European contact in the 17th century, they were believed to number in the tens of thousands of people, with the Grand Village of the Illinois alone having a population of about 20,000. By the mid-18th century, only five principal tribes remained: the Cahokia, Kaskaskia, Michigamea, Peoria, and Tamaroa.

- St. Louis was founded on February 14, 1764, by French fur traders Gilbert Antoine de St. Maxent, Pierre Laclède and Auguste Chouteau, who named it for Louis IX of France.

- Following France’s defeat in the Seven Years’ War, St. Louis was transferred to the Spanish in 1770, but returned to France under a secret treaty with Napoleon.

- With the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, St. Louis became part of the United States. According to legend, on the day of transfer of the territory to the United States in 1803, St. Louis flew under three flags in one day–French, Spanish, and American.

- Between 1840 and 1860, the population exploded with the arrival of many new immigrants. Germans and Irish were the dominant ethnic groups settling in St. Louis, especially in the wake of the German Revolution and the Irish Potato Famine. St. Louis was a strategic location during the American Civil War, but it stayed firmly under Union control.

- The 1874 construction of the Eads Bridge made St. Louis an important link in the continuing growth of transcontinental rail travel–but came too late to prevent Chicago from overtaking it as the largest rail hub in the nation. By the 1890s, St. Louis was the nation’s fourth largest city.

- One of the City’s great moments came in 1904, when it hosted the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in Forest Park. More than 20 million people visited this World’s Fair during its seven-month run, immortalized in the song “Meet Me in St. Louie, Louie.”

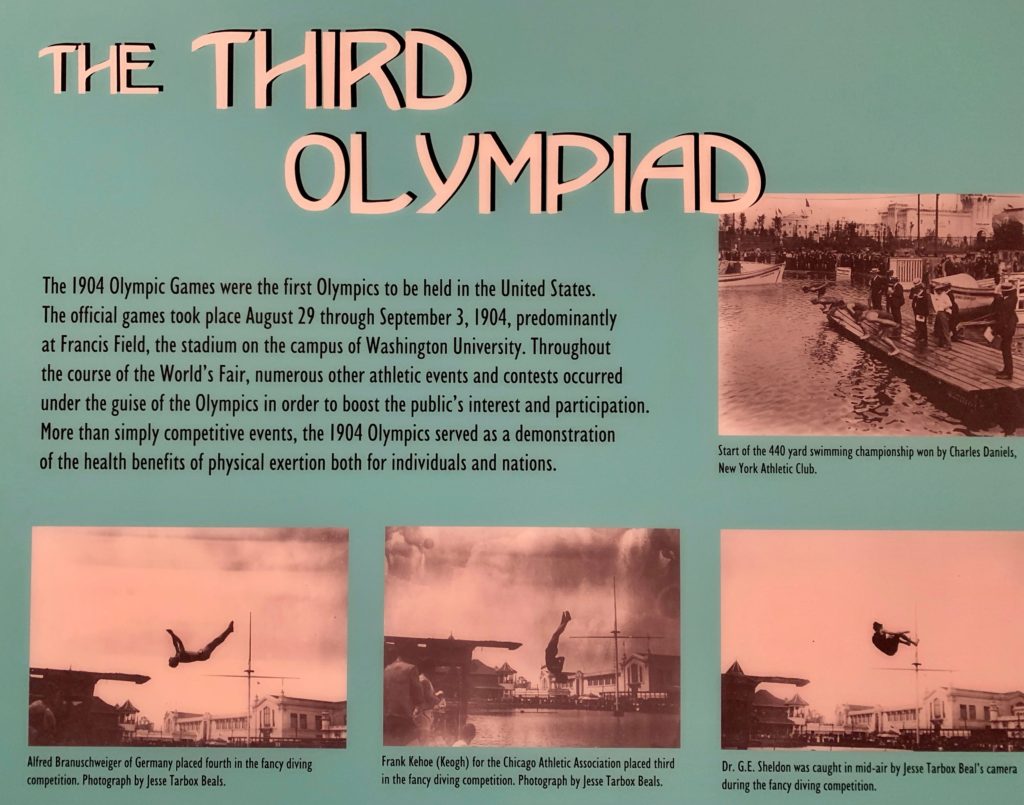

- The 1904 Olympic games were also held in St. Louis, at Washington University’s Francis Field, in conjunction with the fair.

- Through the early 20th-Century, St. Louis continued to industrialize. The increasing popularity of the automobile caused congestion in the downtown area as early as the 1920s. Rapid transit schemes were proposed but never seriously considered. St. Louis was the cite of the nation’s first gasoline station and also, the first automobile accident; today, the region is second in the nation only to the Detroit area in automobile production. During the Great Migration, thousands of African-Americans moved to St. Louis. By 1940, over 800,000 people lived in the City of St. Louis.

- After World War II, the City’s population peaked at 856,000 by 1950. This crowded city had no more room to grow within its fixed boundaries, and much of the housing stock had been neglected during the Great Depression of the 1930s and during World War II. Thus any new growth had to occur in the suburbs in St. Louis County, which St. Louis could not annex. Although some African-Americans from the South, as well as Southeast Missourians, continued to move into St. Louis, earlier immigrant generations gradually moved to suburbia.

- Urban renewal efforts and public housing development programs could not stem the tide of population loss, and in some cases contributed to the decline. Four new interstate highways cut block-wide swaths through neighborhoods, facilitating the exodus to the suburbs. By 1980, the City’s population had fallen to about 450,000.

- The 1965 construction of the Gateway Arch and 1966 construction of Busch Memorial Stadium (home of the Cardinals baseball team) helped promote the revitalization of the central business district. A thirty-year downtown building boom followed.

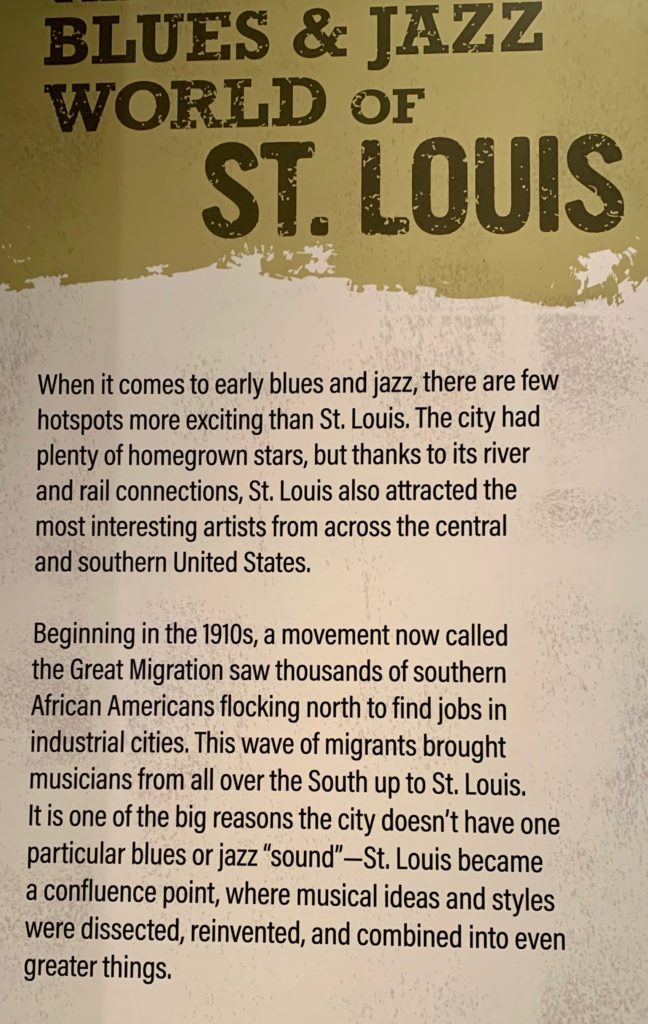

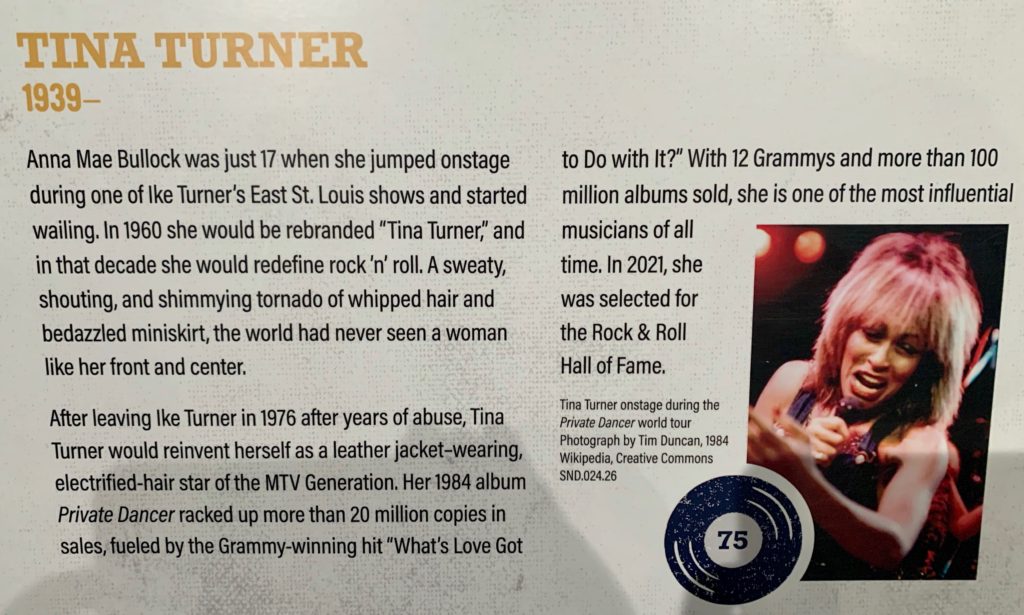

SOUND, a special exhibit at the History Museum in Forest Park, focused on the musical history of St. Louis. Before the famous Blues was Ragtime.

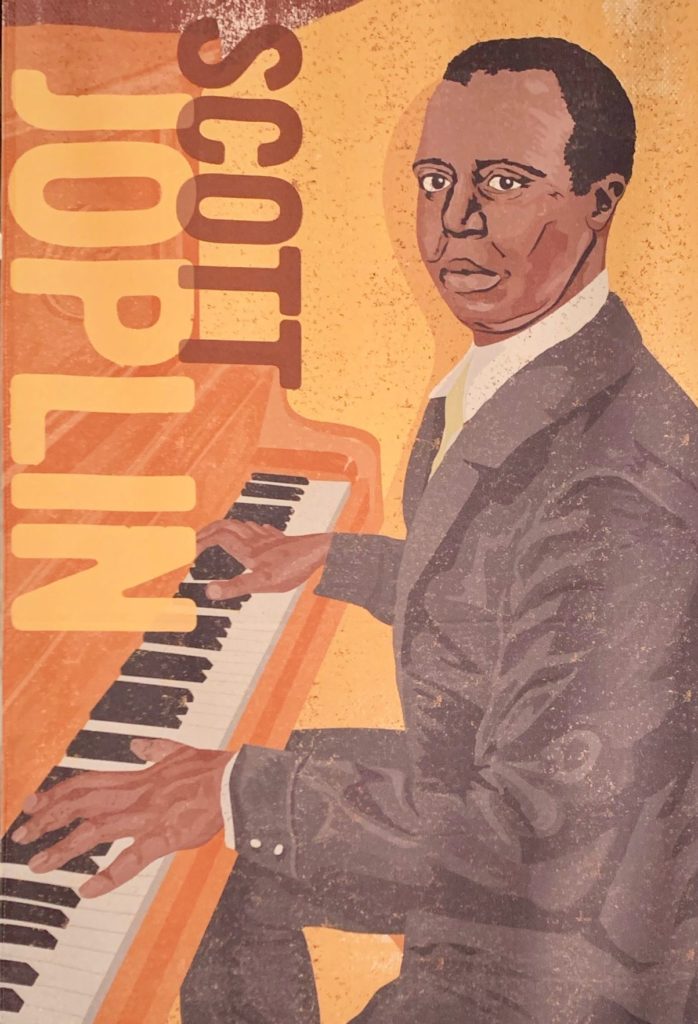

Scott Joplin wrote his first smash hit, Maple Leaf Rag, in 1899. It was named after the Maple Leaf Club in Sedalia, Missouri, 190 miles west of St. Louis, where he worked as house pianist. This was a favorite piece of my grandmother, Lucy Burt Duke Raiza. She played it by ear. Here is a recording I made in 2020.

Maple Leaf Rag provided both Joplin and his publisher, John Stillwell Stark, a steady source of income for more than a decade. Joplin lived in St. Louis from 1900 – 1907, during which he spent most of his time composing, rather than playing in saloons and clubs, as he had before. During his time in St. Louis he published 25 rags, including The Entertainer, which became a huge hit 70 years later, when it was the theme of the Oscar-winning film, The Sting.

Another Ragtime composer who interests me is Louis Chauvin. He collaborated with Scott Joplin to write Heliotrope Bouquet in 1907, then died the next year. I really like the color of the heliotrope flower, which is of the borage family and is used in making perfume. I am practicing this rag now and will add it as soon as it’s ready.

Another Ragtime composer who interests me is Louis Chauvin. He collaborated with Scott Joplin to write Heliotrope Bouquet in 1907, then died the next year. I really like the color of the heliotrope flower, which is of the borage family and is used in making perfume. I am practicing this rag now and will add it as soon as it’s ready.

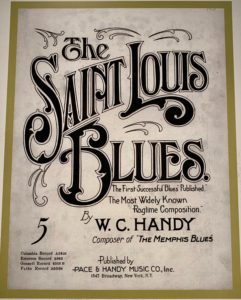

Strangely enough, this quintessential St. Louis song was written by someone who spent only six months in the city. Arriving in 1892, aspiring musician W.C. Handy dreamed of making it big in St. Louis, only to find himself shirtless, penniless, and sleeping on the riverfront. One night, he listened as “shabby guitarists” picked out “the weirdest music.” Today we would instantly recognize it as an early form of the blues. Two decades later, in September 1914, Handy was doing better and that experience came rushing back as inspiration. His Saint Louis Blues would explode to worldwide fame and become the early 20th century’s second most-recorded song after Silent Night.

Strangely enough, this quintessential St. Louis song was written by someone who spent only six months in the city. Arriving in 1892, aspiring musician W.C. Handy dreamed of making it big in St. Louis, only to find himself shirtless, penniless, and sleeping on the riverfront. One night, he listened as “shabby guitarists” picked out “the weirdest music.” Today we would instantly recognize it as an early form of the blues. Two decades later, in September 1914, Handy was doing better and that experience came rushing back as inspiration. His Saint Louis Blues would explode to worldwide fame and become the early 20th century’s second most-recorded song after Silent Night.

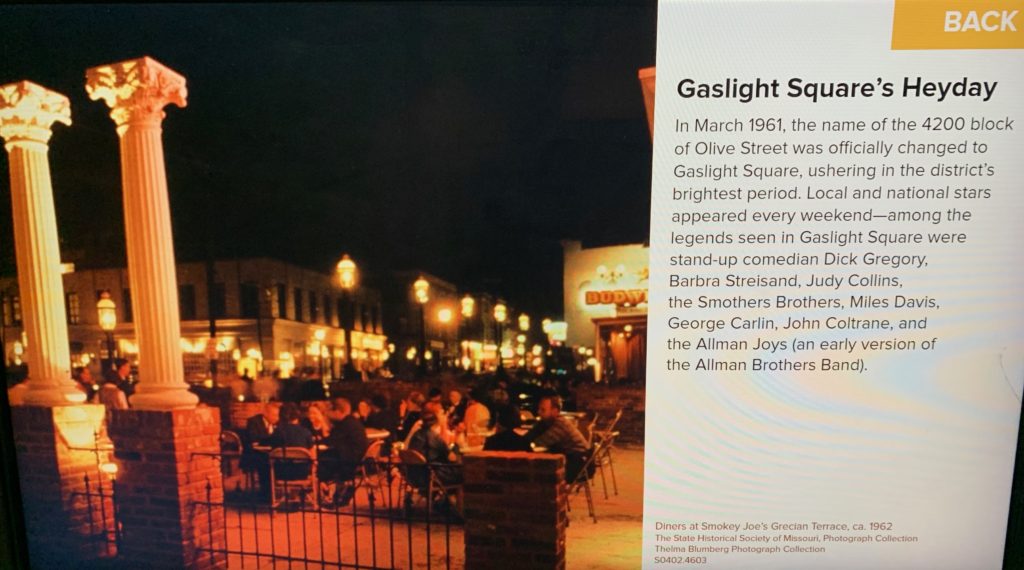

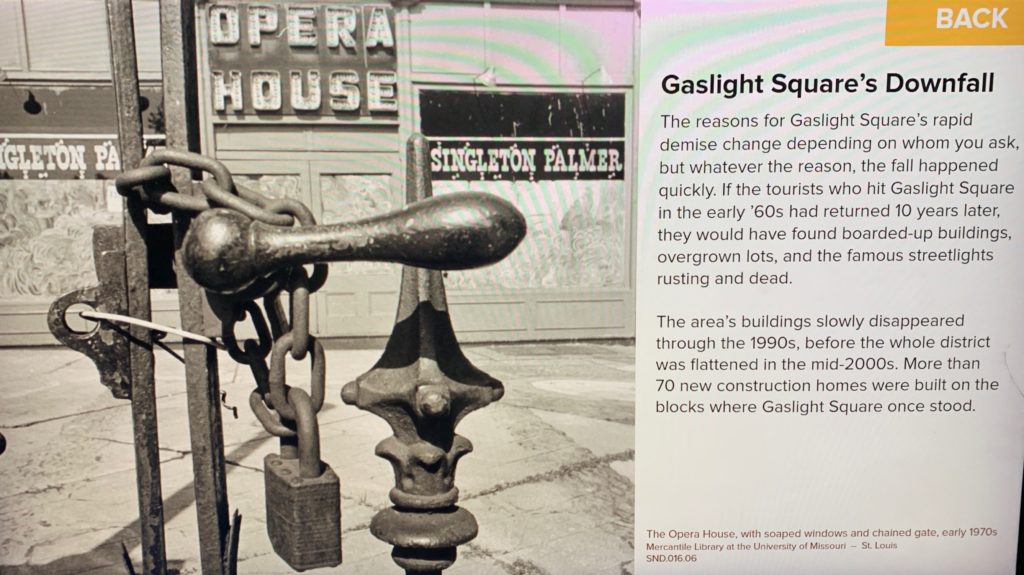

My brother Joel started medical school at Washington University in 1958 and did his residency in Neuropathology at Barnes Hospital from 1962 -67. When his daughter Susan was born in August 1963, I went to help out. It was my first experience with a newborn. There wasn’t time to explore the city, but Joel did give me a quick tour of Gaslight Square, which SOUND chronicled.

Though I didn’t get to hear any live music in 1963, the desire to revisit the city was instilled. Fifty-nine years later it was a great joy to go with my friend-since-first-grade Marjo, who had lived in Saint Charles MO, the oldest city on the Mississippi River, when her husband Keith worked for McDonnell-Douglas Aircraft and she was teaching at the St. Louis College of Pharmacy. I owe her a deep debt of gratitude for doing all the driving–1,097 miles from Borger TX to her house in Kettering OH! Visiting St. Louis fulfilled a long-held dream! We even heard live music. As the sign in front of the Museum of Art proclaims, St. Louis Rocks!

Though I didn’t get to hear any live music in 1963, the desire to revisit the city was instilled. Fifty-nine years later it was a great joy to go with my friend-since-first-grade Marjo, who had lived in Saint Charles MO, the oldest city on the Mississippi River, when her husband Keith worked for McDonnell-Douglas Aircraft and she was teaching at the St. Louis College of Pharmacy. I owe her a deep debt of gratitude for doing all the driving–1,097 miles from Borger TX to her house in Kettering OH! Visiting St. Louis fulfilled a long-held dream! We even heard live music. As the sign in front of the Museum of Art proclaims, St. Louis Rocks!

Leave a Reply