Grant: Then & Now

Why tackle a 1104-page book about a guy who died 135 years ago? Just because he is the General who won the Civil War and the President who tried his best to reconcile North and South, can his journey keep a reader enthralled? Yes! Chernow’s magnificent writing kept me coming back for more. As Coronavirus cases surged and Black Lives Matter protests dominated the news, this book provided perspective on how far our country has come in the century and a half since the Civil War and how very far we still have to go in achieving equal rights and economic justice for all citizens. It also inspired me to look inward to find unconscious biases and unrecognized privilege. In this review, I will highlight the aspects of Grant’s life I found most compelling and include links to relevant books.

Why tackle a 1104-page book about a guy who died 135 years ago? Just because he is the General who won the Civil War and the President who tried his best to reconcile North and South, can his journey keep a reader enthralled? Yes! Chernow’s magnificent writing kept me coming back for more. As Coronavirus cases surged and Black Lives Matter protests dominated the news, this book provided perspective on how far our country has come in the century and a half since the Civil War and how very far we still have to go in achieving equal rights and economic justice for all citizens. It also inspired me to look inward to find unconscious biases and unrecognized privilege. In this review, I will highlight the aspects of Grant’s life I found most compelling and include links to relevant books.

First Chernow introduces Grant’s parents: Jesse Grant, a foreman at a tannery in western Ohio, “a bumptious type common in small towns on the American frontier, a self-assertive windbag and congenital striver, brimming with schemes and bright ideas. Chernow says that it seems clear that “Ulysses S. Grant modeled himself after his mutely subdued mother, Hannah, avoiding his father’s bombast and internalizing her humility and self-control.” Ulysses was born April 27, 1822, followed by two brothers and three sisters over the next seventeen years.

Strict Methodists, the family opposed slavery, dancing, card playing, or cursing. As a boy, Ulysses read every book he could borrow and studied each thoroughly. He began riding horses at age five and was soon breaking in wild horses for local farmers. By age eight, he drove a team of two and hauled enormous logs for his father’s business.

At 17, weighing 117 pounds and standing five feet two inches tall, Ulysses Grant entered West Point; while there, he would reach his full height of five feet eight inches. He found math easy, equestrian classes a breeze, and drawing a strength. “With cartography in its infancy, West Point emphasized drawing so that future officers could sketch rough maps and record a battlefield’s topography. Grant’s uncanny ability to visualize chaotic fighting amid the fog of war would account in no small measure for his military triumphs.”

Many of the generals Grant would encounter in the Civil War he got to know at West Point: on the Union side, William Tecumseh Sherman, George H. “Slow Trot” Thomas, and George B. McClellan; on the other side, Stonewall Jackson and George E. Pickett. Grant graduated in June 1843, twenty-first in a class of thirty-nine, and was sent to Jefferson Barracks not far from St. Louis. “More than two hundred Civil War generals passed through its expansive grounds.” From the Barracks he rode his horse five miles to visit White Haven, the plantation of his West Point roommate, Fred Dent, where he met Fred’s sister Julia, who was to become his wife.

As a border state that permitted slavery, Missouri threw into dramatic relief the tensions roiling the country prior to the Civil War. From his growing liaison with the Dents, Ulysses S. Grant would be forced to straddle two incompatible worlds: the enterprising free labor economy of the North and the regressive world of southern slavery. The Dents owned thirty slaves who grew the cash crops that formed the basis of the family wealth.

At our 2016 family Christmas gathering in Charlotte, cousin Jay engaged a local actress who entertained us with a delightful impersonation of Julia Grant one evening. Gowned in black silk, she convincingly portrayed the devoted wife who saw her husband through trials and triumphs. Chernow, too, had studied Julia Dent Grant closely: “Julia was destined to be the bedrock of Grant’s life, and he was a hero in her eyes long before he became a national hero…..From early on, she believed in him more than he believed in himself…..She bolstered his confidence, soothed his wounds, and pierced through his shyness until he learned to count on her constant strength.”

At our 2016 family Christmas gathering in Charlotte, cousin Jay engaged a local actress who entertained us with a delightful impersonation of Julia Grant one evening. Gowned in black silk, she convincingly portrayed the devoted wife who saw her husband through trials and triumphs. Chernow, too, had studied Julia Dent Grant closely: “Julia was destined to be the bedrock of Grant’s life, and he was a hero in her eyes long before he became a national hero…..From early on, she believed in him more than he believed in himself…..She bolstered his confidence, soothed his wounds, and pierced through his shyness until he learned to count on her constant strength.”

In the spring of 1844 Grant’s regiment was shipped to western Louisiana as part of General Zachary Taylor’s Army of Observation. When a joint resolution to annex the Republic of Texas passed Congress in February 1845, Mexico severed diplomatic relations with the United States and mobilized for war. Mexico believed that the southern border of Texas was the Nueces River; the Polk administration insisted it was the Rio Grande, 130 miles farther south (conveniently doubling the state’s size!). From his first battle with the Mexican army, Grant found himself cool under fire; others found him dependable and exceptionally compassionate.

An appointment as assistant quartermaster for his regiment turned Grant into a compleat soldier, adept at every facet of army life, especially logistics, the mundane stuff that makes for a well-oiled military machine. This provided invaluable training for the Civil War when Grant would need to sustain gigantic armies in the field, distant from northern supply depots.

Why had I never before focused on the Mexican War of 1845-48? It was Just as consequential as the Louisiana Purchase. Chernow depicts General Zachary Taylor (namesake of my children’s elementary school in Arlington VA) as gifted as Napoleon, and the war, a fascinating dress rehearsal for the Civil War. Grant observed Winfield Scott, who replaced Taylor, “assemble a first-rate team of bright junior officers, who later reappeared on opposite sides of the Civil War. With a retentive memory for faces and events, Grant accumulated detailed knowledge about these varied men that he drew on later.” Importantly, he got to study Robert E. Lee up close and knew that he was not endowed with the supernatural abilities that some later ascribed to him.

With the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in the spring of 1848 , U.S. troops under the command of Gen. Winfield Scott ended their occupation of Mexico City. It was a huge bonanza for the United States. Mexico lost about half of its national territory. The United States expanded its territory by nearly a quarter, including Texas, New Mexico, Nevada, Utah, California and parts of several other states. Both slave owners and abolitionists saw this new territory as up for grabs.

After four years of military engagement and three years away from Julia, Grant made a beeline for St. Louis, where her family spent their summers. They married August 22, 1848. Grant’s family registered its disapproval of the Dent clan by boycotting the wedding. “Grant was plunged into his own private civil war, uncomfortably suspended between the easygoing, hedonistic Dents and his thrifty, tightfisted family of die-hard abolitionists.” James Longstreet served as best man; years later he, with Lee, would surrender to Grant at Appomattox.

Next, the Army sent Grant to Detroit, where Julia learned to manage a household without assistance from slaves. When Julia became pregnant in late 1849, she returned to St. Louis to have the baby. Her absence that winter tempted Grant to indulge in heavy drinking, a chronic problem to which Chernow devotes much attention throughout the book. Spoiler alert: he eventually manages to conquer the habit, but it took years. On May 30, 1850 their first son was born, named Frederick Dent Grant after Julia’s father.

Soon Grant learned that he would have to be away from his family for another extended period. His regiment made a treacherous journey over the Isthmus of Panama to reach Oregon and California in the midst of the Gold Rush. This assignment taught Grant more about being a soldier and he met more officers he would later encounter in battle. In April 1854 received the rank of full captain, but immediately tendered his resignation to avoid being tried for drunkenness, a charge that would haunt him for years.

The next seven years were marked by the births of two more sons and a daughter and failure after failure to find a civilian career. Grant just wasn’t cut out to be a farmer or a businessman. The Civil War came along just in time to provide the kind of employment in which he excelled.

The next seven years were marked by the births of two more sons and a daughter and failure after failure to find a civilian career. Grant just wasn’t cut out to be a farmer or a businessman. The Civil War came along just in time to provide the kind of employment in which he excelled.

Of the many battles Chernow details, it was Grant’s Overland Campaign in 1864 that captured my closest attention. The boundary between North and South was then the Rapidan River in Virginia, eighty miles from DC. On May 4, Grant crossed the river and set up headquarters at a “hilltop farm on the Rapidan’s south bank, where he profited from splendid views to track the unceasing movements of his army.” Surely, I thought, that could be or was close to Restless Farm, where we have spent many wonderful times with our friends Elizabeth and Jan Lodal. From 1978 through 2011, we celebrated many events there–Easters, Thanksgivings, and the rehearsal dinner the Lodals hosted the night before Shelby’s wedding in October 2004. As we went tubing on the Rapidan or hiked on Clark Mountain, did we realize that we were on hallowed ground where so many had fought and died in 1864?

When the war ended in 1865, it had claimed 750,000 lives. I thought back to the 2011 Jefferson Lecture Steve and I heard Harvard President Drew Gilpin Faust give at the Kennedy Center. Her lecture was titled “Telling War Stories: Reflections of a Civil War Historian.” She told how deeply religious people in both North and South struggled to reconcile the unprecedented carnage with their belief in a benevolent God. Her 2009 book, The Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War, and Stephen Vincent Benet’s 1929 poem, John Brown’s Body, amplify and personify the battles Chernow describes. Simon Winchester’s The Professor and the Madman: A Tale of Murder, Insanity, and the Making of the Oxford English Dictionary gives a vivid account of the fighting in the Virginia wilderness near the Rapidan River and the surprising outcome one soldier experienced.

When the war ended in 1865, it had claimed 750,000 lives. I thought back to the 2011 Jefferson Lecture Steve and I heard Harvard President Drew Gilpin Faust give at the Kennedy Center. Her lecture was titled “Telling War Stories: Reflections of a Civil War Historian.” She told how deeply religious people in both North and South struggled to reconcile the unprecedented carnage with their belief in a benevolent God. Her 2009 book, The Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War, and Stephen Vincent Benet’s 1929 poem, John Brown’s Body, amplify and personify the battles Chernow describes. Simon Winchester’s The Professor and the Madman: A Tale of Murder, Insanity, and the Making of the Oxford English Dictionary gives a vivid account of the fighting in the Virginia wilderness near the Rapidan River and the surprising outcome one soldier experienced.

Grant’s courtesy at Appomattox became engraved in national memory, offering hope after years of unspeakable bloodshed that peace, civility, and fraternal relations would be restored…Although Grant would do everything in his power to make it happen, the promised era of postwar forgiveness and tranquillity never truly came to fruition. For the South surrendering was one thing, but acceptance of postwar African American citizenship and voting rights would be quite another.

Five days after Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered his army at Appomattox Court House, Virginia, on April 9, 1865, the Grants were invited to join the Lincolns at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, but turned down the invitation. Therefore, they were not present on April 14, when John Wilkes Booth, a famous actor and Confederate sympathizer, assassinated the President. Had Lincoln lived, Reconstruction might have worked. Instead Vice President Andrew Johnson assumed the Presidency. Chernow lamented:

What pretty much guaranteed that Johnson would side with white supremacists was his benighted view of black people. No American president has ever held such openly racist views. “This is a country for white men,” he declared unashamedly, “and by God, as long as I am President, it shall be a government for white men.” In his inverted worldview, he wanted to ensure that the “poor, quiet, unoffending, harmless” whites of the South weren’t “trodden under foot to protect niggers.”

Forty Acres and a Mule. On January 16, 1865 Union General William Tecumseh Sherman proclaimed an order allotting forty acres of land to freed slaves who had worked on that land. Later he ordered the military to provide mules to facilitate the agrarian effort. But on August 16, President Johnson issued an order that allowed southern whites to recapture land confiscated from them during the war–a move that made him heroic to whites while dealing a crushing block to black hopes. It forced freedmen to abandon the forty-acre plots they had started to work, turning the men into powerless sharecroppers, bound to land owned by whites. “Thus, within six months of the end of the Civil War, there arose a broadly based retreat from many of the ideals that had motivated the northern war effort, reestablishing the status quo ante and white supremacy in the old Confederacy.”

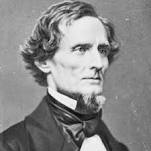

Celebrating the Centennial of the Civil War was a hot topic when I graduated from high school in 1962 and went on to major in history at Rice. Though I was more interested in Ancient and Medieval history, I was aware of the big fuss being made in national media. Only those involved in the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s, however, were asking serious questions as to how much progress had been made for Blacks. Instead, Frank Vandiver, Master of Brown College, committed himself and Rice University to editing the Papers of Jefferson Davis, President of the Confederacy. As President of Brown College, 1965-66, I often was stuck listening to his stories about Civil War battles; my fellow officers usually escaped. Now I find myself asking if research on Jefferson Davis was the best use of funds and talent at Rice from 1964-2015. I didn’t think to ask why focus on Jefferson Davis, rather than on those he subjected to sharecropping. The only time I’ve ever wondered about Davis was in reading Varina, the 2019 novel by Charles Frazier about Davis’s wife. Maybe Grant was too conciliatory. What if Davis and Lee had been executed as the traitors they were?

So, that was THEN, this is NOW. This summer students and alumni at my dear alma mater, Rice University, are raising questions about just how much Black Lives matter to Rice. According to the student newspaper, the Rice Thresher, some have asked for the removal of the statue of William Marsh Rice in the center of the quadrangle. President David Leebron has convened a panel to decide how to proceed in responding to these observations in the Thresher:

William Marsh Rice made money by profiting off the cotton trade and providing loans to local slave owners in the mid-1800s, in addition to enslaving at least 15 individuals in his lifetime. And he did not stop at profiting from slavery — he also served on a Houston slave patrol. When 30-year-old slave Merinda escaped, he offered a “liberal reward for her apprehension and delivery” in the Houston Telegraph.

William Marsh Rice preserved white supremacist views in Rice’s charter, declaring the school to be an institution for “white inhabitants of the city of Houston and the state of Texas.” In 1964, Rice was one of the last southern private schools to desegregate. However, the abhorrent treatment of Black students doesn’t end there. Examinations of past yearbooks reveal the embedding of racism into student life. Photos from the 1920s display Rice’s own Ku Klux Klan chapter. The 1988 Campanile shows students wearing blackface at a party.

Through the statue and use of Willy’s image in marketing, Rice University glorifies a racist who barred Black students from education. Willy is described as a gracious figure who left his earnings for the university. The name “Willy” colors the statue with affection and friendship. Official Rice social media refers to Willy humorously, sharing images of the statue being fitted with a cowboy hat, sporting a Halloween pumpkin and appearing in a frame of Pokemon Go. One Instagram post even begs its audience to consider whether “Willy” would be “a pumpkin spice latte kind of guy.” To not only display the statue, but to treat it with humor for public relations is unforgivable. This goofy and kind “Willy” figure does not exist and never has. Posthumously labeling some slave owners as “good” obscures the evil inherent to slaveholding itself.

Individuals clutching their pearls at the thought of removing the statue argue that erasing its presence “erases history.” They claim that the statue tells of William Marsh Rice’s faults and accomplishments. Nothing about “Willy” reveals the violence integral to his life and fortune, and the university has done a poor job of acknowledging it, too. The statue lacks a formal plaque to inform us that here lies a slave owner, and tour guides are not trained to disclose this either.

Stay tuned. Being a history major has seldom been so exciting! I’m not clutching my pearls. I would welcome a plaque giving a full account of his life. I can imagine Freshmen Orientation featuring facts about Rice and about the original charter limiting enrollment to whites only. Rice’s statue could become a monument to redemption, highlighting that good has come from the fortune he made acting as a creature of his time.

There’s much more to praise in Ron Chernow’s book–a balanced account of his eight years as President, an exciting two-year trip around the world, and how he ended financially bankrupt. But I’ve got to get busy reading more Black history books, to expand on the lists I made in 2013, 2015, 2017, and build on my recent absorption with Frederick Douglass and Lonnie Bunch. I’ve already read Just Mercy by Bryan Stevenson and seen the excellent movie by the same title, as well as the marvelous film, Harriet.

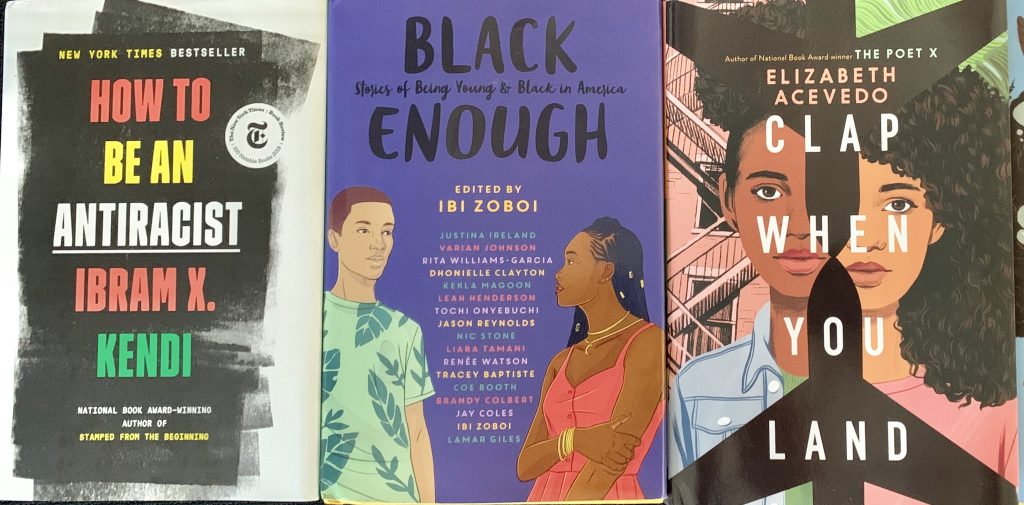

Below are three of the books I ordered in response to a reading list shown on the PBS NewsHour by Jason Reynolds, author and Library of Congress ambassador for young people’s literature. I’m trying hard to find a positive way to express antiracism. There are many valid points about color and culture in Ibram Kendi’s book, but like my friend Jim Cooley, I would rather be FOR certain policies, than just ANTI. Though I am grateful for the privilege of studying tuition-free at Rice, I feel an urgent responsibility to cleanse myself of the prejudices I grew up with and the insensitive ways I have at times acted. Let me know your reactions and suggestions.

Leave a Reply