Artists & Musicians Matter

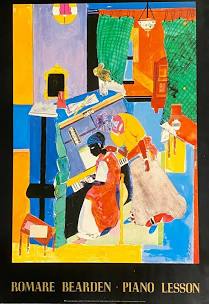

In my recent Self-Examination, I have come to realize how much Black artists and musicians matter to me. This poster by Romare Bearden graced my piano studio in Arlington and now hangs in my guest room in Boynton Beach. I love how it depicts the spirit and complexities of teaching piano. Bearden, born in Charlotte NC, migrated to Harlem, where he worked as both an artist and a musician. I first saw an exhibit about him at the National Gallery of Art in Washington. Then, two years ago, I visited the Romare Bearden park in Charlotte NC.

In my recent Self-Examination, I have come to realize how much Black artists and musicians matter to me. This poster by Romare Bearden graced my piano studio in Arlington and now hangs in my guest room in Boynton Beach. I love how it depicts the spirit and complexities of teaching piano. Bearden, born in Charlotte NC, migrated to Harlem, where he worked as both an artist and a musician. I first saw an exhibit about him at the National Gallery of Art in Washington. Then, two years ago, I visited the Romare Bearden park in Charlotte NC.

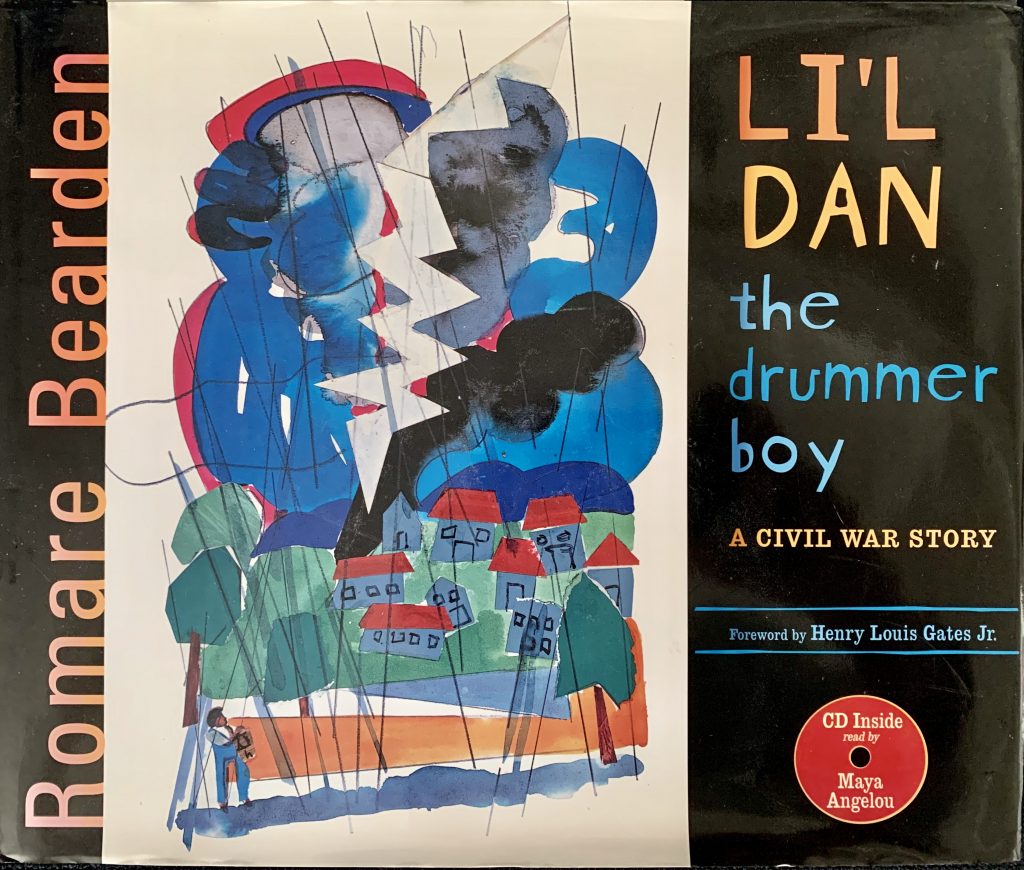

If you lack time for Chernow’s biography of Grant, this book by Bearden provides both adults and children an accurate and colorful introduction to the War that Grant won for the Union.

Li’l Dan learned drumming from a slave who owned a drum brought from Africa. Li’l Dan’s parents were sold away when he was young. He didn’t know what freedom was until Union soldiers took over his plantation. Generously, they took him and his drum along with them. That turned out to be a good move.

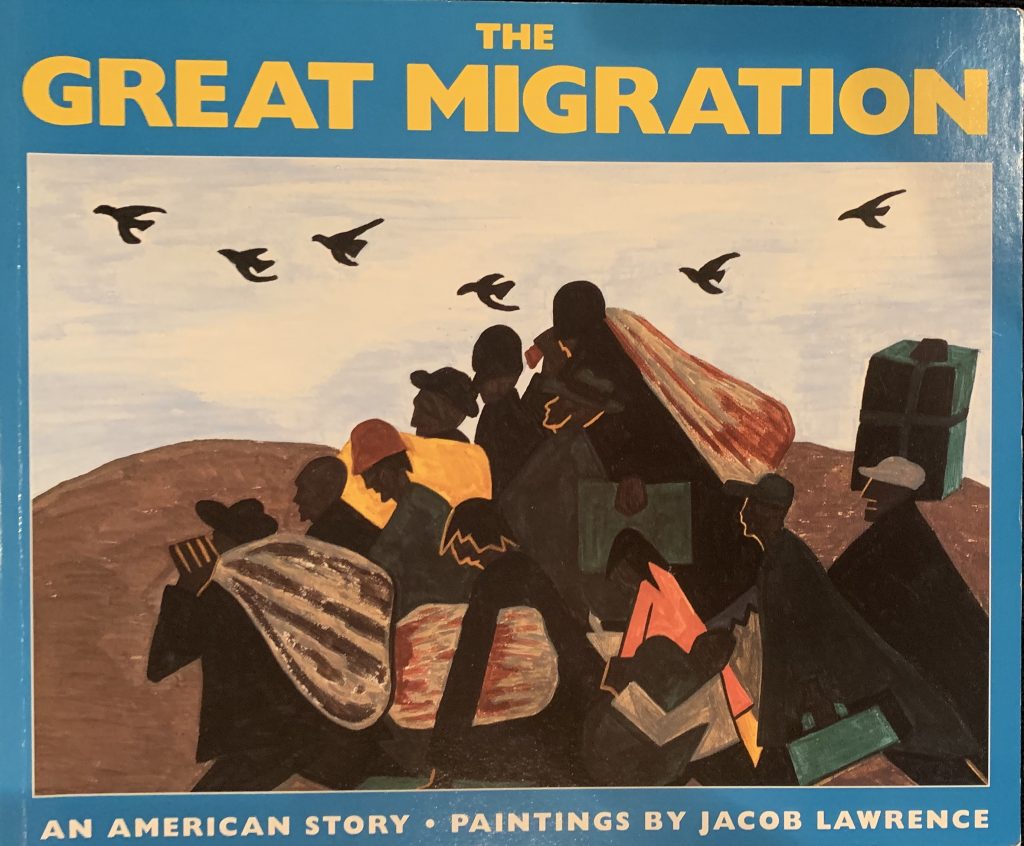

In recent years I’ve come to appreciate the paintings of more Black artists– Jacob Lawrence, Kehinde Wiley, Alma Thomas–and the photography of Gordon Parks. It is a pleasure to share Bearden’s and Lawrence’s books with the second graders I tutor. They may not grasp the full import of the Civil War or the Great Migration, but they readily relate to the art.

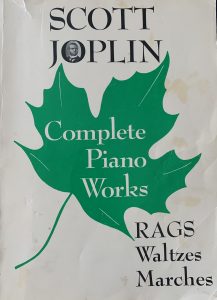

The music of Scott Joplin, born in Texarkana to a former slave father and a freeborn mother, has been important to me all my life. Every time we visited my grandmother in Cleburne Texas, she would play his “Maple Leaf Rag” by ear on her old upright. When I was 16, I learned it and performed it myself. I can still play it whenever anyone asks. Joplin’s “Solace” was the first piece I thought of when we began Hunkering Down. I’ve played and taught many others from Complete Piano Works of Scott Joplin, a collection I’ve had for forty years. In his introduction to this volume, Rudi Blesh describes Joplin’s early musical development. He was just the kind of student every teacher welcomes.

The music of Scott Joplin, born in Texarkana to a former slave father and a freeborn mother, has been important to me all my life. Every time we visited my grandmother in Cleburne Texas, she would play his “Maple Leaf Rag” by ear on her old upright. When I was 16, I learned it and performed it myself. I can still play it whenever anyone asks. Joplin’s “Solace” was the first piece I thought of when we began Hunkering Down. I’ve played and taught many others from Complete Piano Works of Scott Joplin, a collection I’ve had for forty years. In his introduction to this volume, Rudi Blesh describes Joplin’s early musical development. He was just the kind of student every teacher welcomes.

When barely seven he discovered a piano in a neighbor’s home. Given an opportunity to express himself, he displayed his natural musical gifts almost immediately. Soon the neighborhood was listening and talking. His father, Giles Joplin, though determined that his son learn a trade, scraped money together and bought a second-hand square piano.

The boy was at this instrument day and night and before he was eleven years old he was improvising so remarkably that the became the talk of the Negro community. Rumors spread to the white community through servants’ talk–Mrs. Joplin was a laundress.

In those days almost every Midwestern town had its German music teacher, a paragon immersed in the three B’s, who generally taught piano. Such a man in Texarkana heard young Joplin play and as a result gave him free lessons in piano, sight reading and the principles of harmony.

The name of the German piano teacher is lost to history, but he was an early forerunner of teachers who teach talented kids for reduced rates through the MusicLink Foundation. I was a MusicLink teacher from its beginning in 1993 to my retirement in 2011 and still support the work of the Foundation.

Bach, Brahms and Chopin are worthy masters whose music I play often, but examining myself for prejudice made me ask what happened to the “Music of the African Diaspora” that was my piano studio theme in the fall of 2007? That theme was inspired by having met William Chapman Nyaho at a Music Teachers National convention. So I looked him up again. Here he is, playing, appropriately, his own arrangement of “Troubled Water.” Now I’ve ordered two more of his books presenting composers of the African Diaspora.

Nyaho’s arrangement of “Troubled Water” is based on the traditional spiritual “Wade in the Water,” which is in Songs of Zion, a hymnal Susan Staines gave me when I taught her sons. Many years ago, Steve and I saw an unforgettable performance of “Wade in the Water” by Alvin Ailey’s American Dance Theater. The company still performs it.

The words of this hymn resonate today. We are in “troubled water” and we must wade through it! Update: on February 6, 2021, Steve and I saw this video from Lincoln Center. See on a full screen the Alvin Ailey Dance Company in 33 minutes of fantastic dancing. It includes “Wade in the Water” and several other spirituals, concluding with the most spirited expression of “Go Down, Moses” that I have ever seen or heard.

On July 12, 2020 Palm Beach Post columnist Eliot Kleinberg wrote about another hymn in Songs of Zion, “Lift Every Voice and Sing.” It is known as the Black National Anthem.

James Weldon Johnson, a giant of the Harlem Renaissance believed the best way to reduce racism was for Black people to produce memorable literature and art, so whites would look at them differently. [Ibram X. Kendi would label this notion assimilationist.]

Johnson was born in 1871 in Jacksonville, Florida, of Bahamian-American parents. He attended high school and college in Atlanta, where he founded a campus newspaper. He then returned to head Jacksonville’s segregated Stanton School where his mother had taught. In 1898, he was the first Black person admitted to the Florida Bar since reconstruction.

In 1901, he and his brother John packed up and left Florida for New York. They had a new calling: the theater. In all, the brothers wrote some 200 songs for Broadway. The anthem was first a poem by James and later set to music by John.

In the Old Testament, people made offerings to atone for their sins. For the sins listed in my Self-Examination, I offer this performance of “Lift Every Voice and Sing” by the Winston-Salem State University Choir.

‘Til earth and heaven ring

Ring with the harmonies of Liberty

Let our rejoicing rise

High as the list’ning skies

Let it resound loud as the rolling sea

Sing a song full of the faith that the dark past has taught us

Sing a song full of the hope that the present has brought us

Facing the rising sun of our new day begun

Let us march on ’til victory is won

Bitter the chastening rod

Felt in the days when hope unborn had died

Yet with a steady beat

Have not our weary feet

Come to the place for which our fathers sighed?

We have come over a way that with tears has been watered

We have come, treading our path through the blood of the slaughtered

Out from the gloomy past

‘Til now we stand at last

Where the white gleam of our bright star is cast

God of our silent tears

Thou who has brought us thus far on the way

Thou who has by Thy might

Led us into the light

Keep us forever in the path, we pray

Lest our feet stray from the places, our God, where we met Thee

Lest, our hearts drunk with the wine of the world, we forget Thee

Shadowed beneath Thy hand

May we forever stand

True to our God

True to our native land

Leave a Reply