Self-Examination

Protests this summer have challenged me to examine myself for deep-rooted, but obsolete mindsets. After all, I am a fourth-generation Texan, raised in a state that seceded from the Union. As a teen in the early 60s, I was only dimly aware of student sit-ins and civil rights marches. I had no classes with Blacks until graduate school. But Rice University instilled in me a respect for facts and these three facts gripped me:

Protests this summer have challenged me to examine myself for deep-rooted, but obsolete mindsets. After all, I am a fourth-generation Texan, raised in a state that seceded from the Union. As a teen in the early 60s, I was only dimly aware of student sit-ins and civil rights marches. I had no classes with Blacks until graduate school. But Rice University instilled in me a respect for facts and these three facts gripped me:

-

- Young Black males were 21 times more likely to be killed by police than their White counterparts between 2010 and 2012.

- The median wealth of White households is a staggering 13 times the median wealth of Black households.

- Black people are 5 times more likely to be incarcerated than Whites.

These facts, along with many others, provide evidence that U.S. law enforcement and court systems and housing policies still retain biases in favor of Whites. With racism embedded in our systems, we can’t live up to our goals of liberty and justice for all.

What exactly is racism? Am I, personally, a racist? As a subscriber to Socrates’ famous dictum, “The unexamined life is not worth living,” I needed to define terms and assess where I stand. With no travel plans for Florida’s hottest months, I had time to hit the books. Thinking about race was not new to me. Among relevant books I had read and discussed in the last decade, four stood out:

- Isabel Wilkerson’s The Warmth of Other Suns: the Epic Story of America’s Great Migration, (2011). explained why millions of Blacks left the South from 1915-70 for better opportunities, only to find more challenges in northern and western states.

- Debby Irving’s Waking Up White and Finding Myself in the Story of Race (2014) taught me the privileges I have due to the color of my skin. One example: because only a small fraction of Black servicemen in WW II were able to take advantage of the GI Bill, Black families were unable to build wealth as home owners, as Whites did. Redlining by government agencies kept Blacks boxed in.

- Michelle Obama’s Becoming (2018). Her grandfather was a part of the Great Migration. Her parents in Southside Chicago concentrated on education for Michelle and her brother. After excelling at Princeton and Harvard Law School, she faced challenges in the corporate world and close scrutiny as First Lady.

- Claude Steele’s Whistling Vivaldi: How Stereotypes Affect Us and What We Can Do, (2011) inspired me to reconsider the stereotyping I had experienced myself many years ago. Am I guilty of applying labels to people with whom I disagree? Yes! Ouch! I resolve to keep an open mind, inquire about reasons and listen calmly.

Since lockdown began on March 13, I had read and written reviews of two big, thick biographies: David Blight’s Frederick Douglass and Ron Chernow’s Grant. Both showed how unfair society was to Blacks in the 19th century America and established baselines for current comparisons. By July I was ready to bring myself up to date. Friends in my Arlington book group, with whom I had reconnected via Zoom, directed me to the work of Ibram X. Kendi.

In Stamped From the Beginning: the Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America (2016), Kendi starts right out with the origins of racist ideas and how, though completely unsubstantiated, they were adopted and expounded upon by Cotton Mather in 17th-century Boston. By the time I finished reading about Mather, I switched to Jason Reynold’s “remix” of the book, which I found easier to read. So much so that I stopped to order copies for my oldest grandchildren (ages eleven and twelve).

Reynolds‘ remix helped me sort through the ideas and influences of Thomas Jefferson, abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison and sociologist W.E.B. DuBois, right up to political activist Angela Davis, who is just my age. It hit me that in my course in “Intellectual History” at Rice 55 years ago, we failed to even ask what views on slavery were held by Voltaire, Hume, and other Enlightenment thinkers. Kendi reveals how benighted their views were. Jefferson read their books. He lived with his own contradictions; indeed, he fathered several chidden by his slave, Sally Hemings. (I had read Annette Gordon-Reed’s The Hemingses of Monticello: an American Family when it came out in 2009). In this earlier post, I related how my views on Thomas Jefferson have evolved, but my self-examination revealed scant recall about other influencers. I gave the remix away and returned to Kendi’s original Stamped From the Beginning for more substance to ponder.

In his latest book, How to Be An Antiracist, Kendi crafts exact definitions that force readers to stop and think.

One either believes problems are rooted in groups of people, as a racist, or locates the roots of problems in power and policies, as an anti-racist. One either allows racial inequities to persevere, as a racist, or confronts racial inequities, as an antiracist. There is no in-between safe space of “not racist.” The claim of “not racist” neutrality is a mask for racism.

When he weaves his themes and terms together in the last chapter, his passion soars and reveals his deep humanity. I see Dr. Kendi becoming an important voice in our future. In this 2019 video he was a professor at American University in Washington DC. On July 1, 2020, he assumed the position of director of the Center for Antiracist Research at Boston University. He turned 38 August 13.

This video introduces the complexities of racism that his books treat in more detail.

My next step was reading Eddie S. Glaude, Jr’s Begin Again: James Baldwin’s America and Its Urgent Lessons for Our Own. Glaude, Chair of the Center for African American Studies at Princeton University, defines the basic problem in American society as the “value gap,” the idea that in America white lives have always mattered more than the lives of others. His “value gap” fits with Baldwin’s analysis.

Baldwin’s understanding of the American condition cohered around a set of practices that, taken together, constitute something I will refer to throughout this book as the lie. The idea of facing the lie was always at the heart of Jimmy’s witness, because he thought that it, as opposed to our claim to the shining city on a hill, was what made America truly exceptional. The lie is powerful architecture of false assumptions by which the value gap is maintained. These are the narrative assumptions that support the everyday order of American life, which means we breathe them like air. We count them as truths. We absorb them into our character.

Baldwin was active as a writer from the late 1950s until his death in 1987. He took leaders like Roy Wilkins of the NAACP and Whitney Young of the National Urban League to task, saying they “had come to power not so much because of their efforts to make the Negro a first class citizen, but to keep him content as a second class one.” Baldwin defended Stokely Carmichael and other advocates of Black Power. In fact, Glaude notes, “Baldwin had mastered the idiom of Black Power. Invective. Excess. A relentless truth telling, without concern for civility or comfort.” He and Martin Luther King Jr. agreed on the basics, but never had a warm relationship. “Baldwin still hoped, even in his angriest of moments, that we, all of us, could be better.

Baldwin was active as a writer from the late 1950s until his death in 1987. He took leaders like Roy Wilkins of the NAACP and Whitney Young of the National Urban League to task, saying they “had come to power not so much because of their efforts to make the Negro a first class citizen, but to keep him content as a second class one.” Baldwin defended Stokely Carmichael and other advocates of Black Power. In fact, Glaude notes, “Baldwin had mastered the idiom of Black Power. Invective. Excess. A relentless truth telling, without concern for civility or comfort.” He and Martin Luther King Jr. agreed on the basics, but never had a warm relationship. “Baldwin still hoped, even in his angriest of moments, that we, all of us, could be better.

Glaude concludes that we must Begin Again:

We stand in the ruins. Modern conservatism has collapsed. Its claims about the value of small government, the importance of tax cuts for the rich, and the benefits of deregulation and privatization have resulted in most Americans drowning in profound uncertainty about their future and their children’s future and have left the planet mortally wounded. All that is left of this once-vaunted ideology are appeals to our lesser angels in order to divide Americans along the fault lines that have been a part of this democratic experiment since the very beginning.

Americans must walk through the ruins, toward the terror and fear, and lay bare the trauma that we all carry with us. So much of American culture and politics today is bound up with the banal fact of racism in our daily lives and our willful refusal to acknowledge who benefits and suffers from it. Underneath it all is the lie that corrupts American life.

We have to choose life, Baldwin repeatedly said. Salvation is found there: in accepting the beauty and ugliness of who we are in our most vulnerable moments in communion with each other. There, in love, a profound mutuality develops and becomes the basis for genuine democratic community where we all can flourish, if we so choose.

My Bible, specifically Micah 6:8, gave my self-examination historical and moral perspective. “What does the Lord require of you? To act justly, and to love mercy and to walk humbly with your God.” That is my basic Credo. Kendi and Glaude made me face my sins. I recalled certain times when I had acted as though I deserved preferential treatment. Or times when I had treated a person with darker skin with less respect. I’m sure I must have committed many microaggressions. My actions were neither overt nor intentional, but they must have hurt.

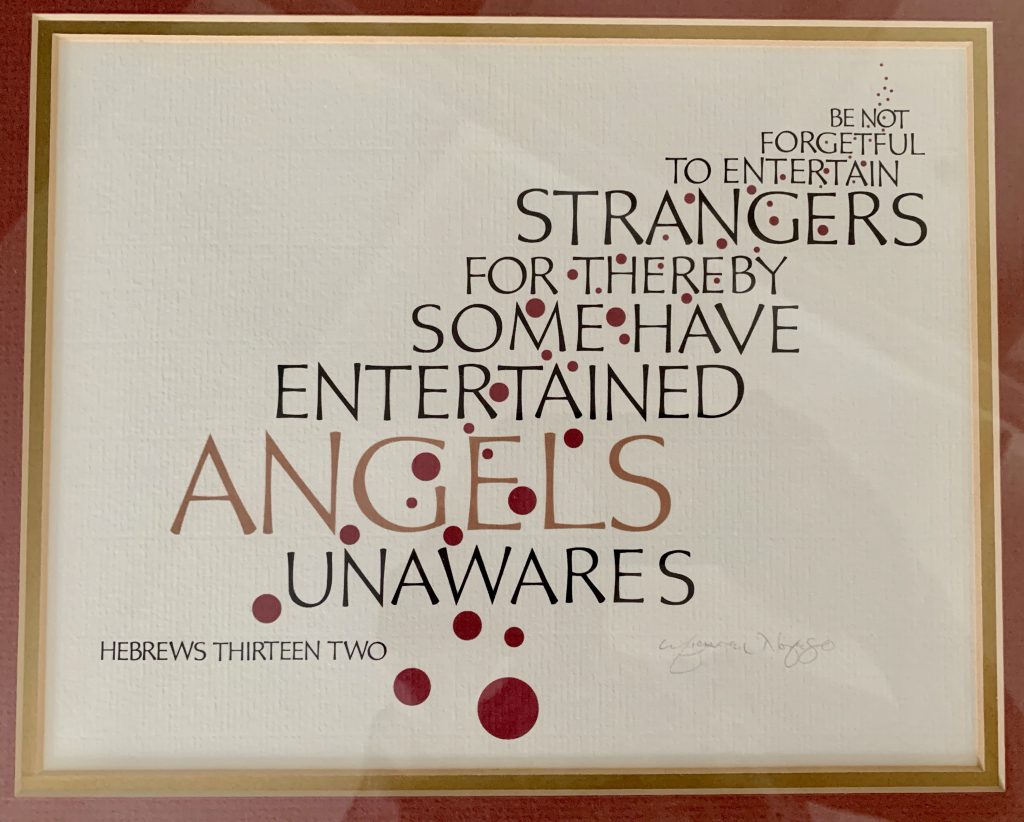

So I keep asking that old question, “what would Jesus do?” Matthew 7:5 ratifies self-examination: “You hypocrite, first take the plank out of your own eye, and then you will see clearly to remove the speck from your brother’s eye.” Jesus, who undoubtedly had dark skin, would, I believe, reach out to those who feel marginalized and make them feel included. Jesus modeled caring for the least (poor people) and the lost (strangers in a strange land). Special thanks to Norie Gelfond in my Monday morning Bible study group for sharing an Audible copy of Rob Bell’s book, What is the Bible? to listen to on my daily walks. Every morning I learn the context and deeper meaning of yet another Bible story. These ancient stories have uncanny relevance to our current mess.

A person who exemplifies Micah 6:8 is Bryan Stevenson, author of Just Mercy and founder of the Equal Justice Initiative in Montgomery, Alabama. His experience in freeing scores of men on death row demonstrates how unequal “justice” can be. As a result of his team’s efforts over the last thirty years there are now two remarkable sites in Montgomery. In Begin Again Eddie S. Glaude Jr. describes his visit to the Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration. Then he walked less than a mile to the National Memorial for Peace and Justice to contemplate the scope and horror of lynching. As soon as this pandemic is past, I want to visit Montgomery and see these inspiring places myself. Steve and I saw the movie Just Mercy last fall. Carol Starr directed me to the HBO documentary True Justice. Both are accurate and fair; I wish everyone in America could watch them. Stevenson is a role model for all of us.

A person who exemplifies Micah 6:8 is Bryan Stevenson, author of Just Mercy and founder of the Equal Justice Initiative in Montgomery, Alabama. His experience in freeing scores of men on death row demonstrates how unequal “justice” can be. As a result of his team’s efforts over the last thirty years there are now two remarkable sites in Montgomery. In Begin Again Eddie S. Glaude Jr. describes his visit to the Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration. Then he walked less than a mile to the National Memorial for Peace and Justice to contemplate the scope and horror of lynching. As soon as this pandemic is past, I want to visit Montgomery and see these inspiring places myself. Steve and I saw the movie Just Mercy last fall. Carol Starr directed me to the HBO documentary True Justice. Both are accurate and fair; I wish everyone in America could watch them. Stevenson is a role model for all of us.

Before I’m ready to Begin Again, as prescribed by Eddie Glaude, I need to come to terms with mistakes I’ve made in my lifelong quest to expose myself to new places, new people, and new ideas. Have there been times when I have unintentionally insulted people in my family, my children’s schools or in my interactions with people from other countries?

Let’s start with exposure to other cultures. Each Thanksgiving I admire how effortlessly Leslie, my daughter-in-law, switches languages as she introduces her extended family and friends, many of whom were born in Colombia, Cuba or Peru. Her dinners reach the level of “profound mutuality” that Eddie Glaude portrays as a goal. So I asked her recently if anyone had complained about any comments I had made. “Not at all,” she said. “David has told me about all the exchange students you welcomed when he was growing up. My family never did that.” Whew, maybe I passed one question on one exam .

From 1979 – 89, we hosted several students from Germany, France and Switzerland through the Experiment in International Living, my way of repaying the hospitality I had enjoyed in Austria in 1965. Because of the Experiment’s limited reach, we never had anyone from Africa, nor had I traveled in Africa until just last fall. I liked seeing people working together in Tanzania. What we need now in America is Harambee, a Swahili word for pulling together, helping each other, caring and sharing. A friend told me about a Black-owned bookshop in Alexandria named Harambee. I have ordered two more books from them.

From 1979 – 89, we hosted several students from Germany, France and Switzerland through the Experiment in International Living, my way of repaying the hospitality I had enjoyed in Austria in 1965. Because of the Experiment’s limited reach, we never had anyone from Africa, nor had I traveled in Africa until just last fall. I liked seeing people working together in Tanzania. What we need now in America is Harambee, a Swahili word for pulling together, helping each other, caring and sharing. A friend told me about a Black-owned bookshop in Alexandria named Harambee. I have ordered two more books from them.

From 1976 – 92, my three children had mostly wonderful teachers in Arlington Virginia public schools. Lilli’s second grade teacher, who happened to be Black, had difficulty managing a combined class of 2nd and 3rd graders in an open classroom, which was a new concept in 1978. When a new principal, Ralph Stone, came on board the next year, that teacher was let go. Later when Shelby was in 5th grade, Dr. Stone let me know that an outstanding Black teacher was offended by something I had said in a meeting. Sadly, I never found out what it was I had said. If I had I gone to see her to resolve the issue, I wouldn’t be left wondering. Lesson: address criticism and make amends right away.

After Shelby’s orthopedic surgeries in 1980 I took her for a check-up at Children’s Hospital in DC and encountered my first Black doctor, a resident assigned to Dr. Douglas McKay, her surgeon. I thought he was well-informed and quite professional–why do I remember his color? It’s taken me this long to recognize the racism an orthopedist in Arlington showed. Comparing notes about a doctor I planned to take Shelby to see, my friend reported what he had said about her son: “He’s got really good co-ordination for a white kid.” Kendi shows us how ascribing natural abilities to Blacks fails to credit their practice and hard work. Examples abound in sports and music, areas in which Blacks were allowed to flourish.

Achieving diversity in my piano studio was difficult, so I was thrilled when my friend Joanne Haroutounian started MusicLink in 1993, linking students who couldn’t afford private lessons with willing teachers. Levita, my first Black student, came every Saturday morning for several years for a token $5 per lesson. By 2007 I was organizing “play-ins” at Tysons Corner for Northern Virginia MusicLink students and serving on the national board. Glad to report this organization is still going strong.

Since retiring, I have missed MusicLink activities and kids in general. My twin granddaughters born in 2013 kept me busy until they started school. Since 2017 I have volunteered at nearby Crosspointe Elementary. In 2018 I began tutoring second graders, one hour per week each, guided by the Literacy Council of Palm Beach County. My experiences in Title I schools has helped me to identify the children by their interests, rather than their color. Last year Gandhy preferred to read in the garden; Raniyah, in the front hall. Until our sessions ended abruptly in March, I could count on Zakee to measure any distance mentioned in a book; Jason couldn’t get enough books about sharks. With unintentional foresight, Lisa asked me to show her how to wash her hands. I look forward to returning to tutoring as soon as safely possible.

My self-examination is incomplete without considering how Blacks have influenced by explorations of art and music. For more on this subject see Artists and Musicians Matter.

Leave a Reply